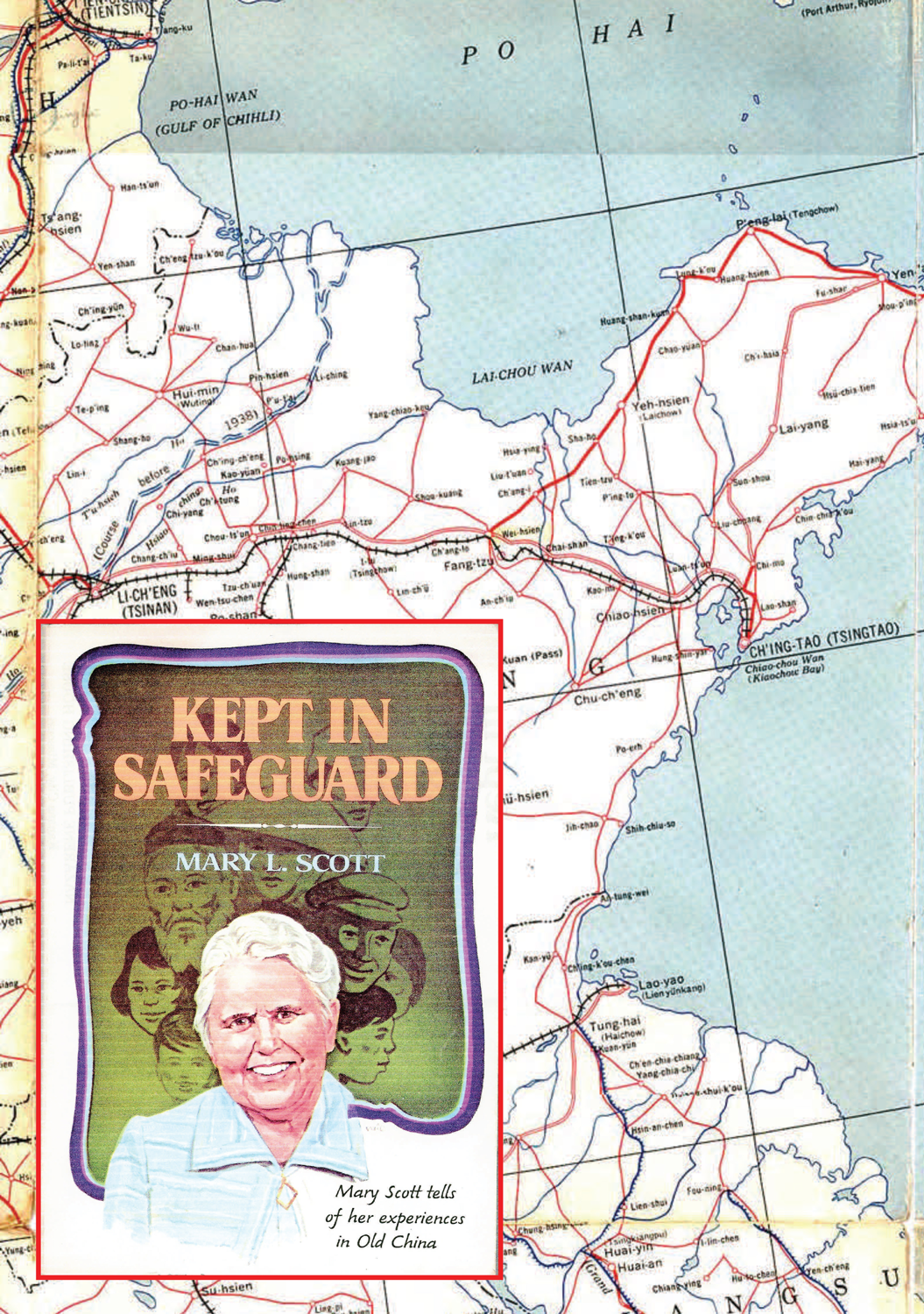

- by Mary L. Scott

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

With the coming of the paratroopers, everything changed. The flag of the “Rising Sun” was taken down, and “Old Glory” was raised on the top of building number 23. What a thrill it was to see the Stars and Stripes blowing in the wind over our heads.

With the coming of the paratroopers, everything changed. The flag of the “Rising Sun” was taken down, and “Old Glory” was raised on the top of building number 23. What a thrill it was to see the Stars and Stripes blowing in the wind over our heads.

Chinese merchants from Weihsien sent in carts of meat, vegetables, and grain.

Big B-29s, most of them from Saipan or Guam, came at regular intervals to drop tons and tons of food, medicine, and clothing into the fields nearby. Many a woman in camp wore GI shorts during those last weeks in camp. All rationing of food ceased and internees literally made themselves sick eating Spam, canned peaches (Del Monte, no less!), K-rations, and chocolates in spite of the leaflets dropped warning us,

“DO NOT OVEREAT OR OVERMEDICATE.” But it tasted good going down at least!

A big victory dinner was held on the ball field with tables piled high with food. I thought of that verse in the 23rd psalm: “Thou preparest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies.” The Japanese guards looked on as we celebrated. Whether they were given a share in this abundance I do not know. I hope so, for they had suffered short rations as well as we.

When I speak of enemies, I mean only enemies of our nation.

We had been treated well.

We had not suffered the privation or horrors of some other civilian camps to the south of us or the atrocities perpetrated at Belsen or Buchenwald. It was our good fortune, under the providence of God, to have as our commandant a Japanese gentleman. Though not a professing Christian, he had received his precollege education in mission schools in Tokyo and had taken his college work in the United States. In fact, he had been living in the States when the war broke out, was interned in California, but repatriated in the first exchange of prisoners in the summer of 1942. No doubt all these experiences were factors in the mild rule which we experienced.

One of the greatest luxuries enjoyed after the arrival of the paratroopers were the walks in the countryside or the trips to the nearby walled city of Weihsien, usually for a Chinese meal.

We enjoyed the magazines the boys brought in, though there were many terms and abbreviations which had come into use during the war with which we were totally unfamiliar.

One day a Britisher said to me, “Mary, what’s a pin-up girl?” I performed some mental gymnastics trying to figure it out, but finally had to confess that I didn’t know.

Finally, we went to our rescuers with a list of terms and abbreviations we did not know (LCVP, LST, etc.) and asked them to make up a glossary so we could post it on the bulletin board.

We were as hungry for news and understanding as we had been for food.

Each internee in camp was permitted to send two radiograms anywhere in the World via the Army radio.

Though the messages were short (I don’t remember how many words we were allowed), I sent a message to Dr. Jones in Kansas City and one to my brother, Ed, in Hammond, Ind. While in the beginning it was out of the question to airlift all of us out of camp, the rescuers, very soon after their arrival, requested the quarters committee to prepare a list of those seriously ill or in need of immediate medical attention. A list of the children whose parents were in West China was also provided. Internees in these two categories were flown out as soon as transportation could be arranged in Kunming.

On September 25, the first large contingent of about 600 internees bound for home, wherever that might be, left camp for Tsingtao, the seaport about 100 miles away. Here they were put up in the “Edgewater Beach” hotel which had been commandeered by the American army.

They wrote back telling of the plush carpets, spacious rooms, dining tables with sparkling white tablecloths and cutlery “a mile long,” to say nothing of the variety of delicious food, including steaks. All these luxuries they enjoyed until the ships arrived that would take them to England, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, or Canada.

The next large group of about 600, made up largely of older people and mothers with children who were returning to points in China, was all ready to leave by train. In fact, some were already waiting at the train station when word came that the Communist guerrillas had blown up the railroad bridge. Six hundred extremely disappointed and frustrated people had to return to camp.

The army officers in charge decided that it would be necessary to organize an airlift because they had no assurance that, if they repaired the bridge, it would not be blown up again.

On October 14, the huge operation began, using mostly C47s with bucket seats along the sides.

I was in the next to the last load to leave the Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center and enjoyed my first aeroplane ride. I must confess that I was glad when we landed at the Peking airport.

The internment camp chapter of my life in China was closed, but it left rich rewards and memories.

By the grace of God, what in itself could not be called good had brought new insights and experiences which God worked in and through to enrich my fellowship with Him and strengthen my faith that “all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose.” I wouldn’t take $1 million for the experience—or give a nickel for another one unless it came in the path of duty and in His will.

#

[further reading] ...http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/KeptInSafeguard-MaryScott/MaryScott(web).pdf

#