- by Emmanuel Hanquet

Father Emmanuel Hanquet remembers … (September 2002)

Father Palmers and Unden decided to work in the bakery.

That helped our group a lot, since every three days, we could bring back a big loaf of bread that was issued as a premium to us heavy workers, going to work at 5 in the morning.

I myself chose to work in kitchen number one and got a job as the 5th “roast-about”. Every third day, I had to work hard there, beginning at 6 a.m., and learned the job as much as possible. So much that, after ascending every rank in the team, I was finally assigned the job of “chef-cook”.

We were a happy team of 7, joyful and cooperating. My assistant was an American named Zimmerman who had a Russian wife who knew a lot about cooking and helped us to create and prepare new dishes. At the beginning, in that kitchen, there were no ladles, spoons and special utensils to ditch the food out, so, we had to ask the repair shop to make new instruments out of tins. The same for the covers of the “kuo”.

There were 5 of them, large kettles of which the bigger one contained twelve buckets of water.

We even had a team song, that was taught to us by a young British from Tsingtao and we sung our song every now and then, especially when we saw some protestant reverend passing alongside the small windows above our kettles. We sang it with a certain smile and even a point of derision for the Holy Book --- it goes;

(like a nursery rime)

“ The best book to read is the Bi-i-i-i-ble (bis)

“ If you read it every day

“ It will make you on the way

“ While turning in our kettles,

(at this point, we yelled) “OUPS!”

“ The best book to read is the Bi-i-i-i-ble “

---- and so on ----

I worked in the kitchen for almost a year. After that, I was assigned to making noodles with two new friends, Langdon Gilkey and Robin Strong.

Somebody had discovered in the attic of the old mission a machine that looked like a wringer for drying the laundry. The machine was made of two cylinders turning in opposite directions and closed together. After many trials of mixing flour with the right proportion of water --- neither too much nor too little --- and by feeding the device with the good mixture between the two cylinders turning slowly, we obtained noodles that could be boiled as such for a few minutes and were a regal for all of us.

It did not last long for me and I switched to “woodcutter”, chopping wood for the stoves of the hospital. ….

N.D.L.R.

(by Leopold Pander)

(by Leopold Pander)

... and here is the true story of how Father Emmanuel Hanquet’s adventure in Kitchen #1 finally ended:

... it is as he told it to me at his home in Louvain-la-Neuve — when he was still alive and healthy !

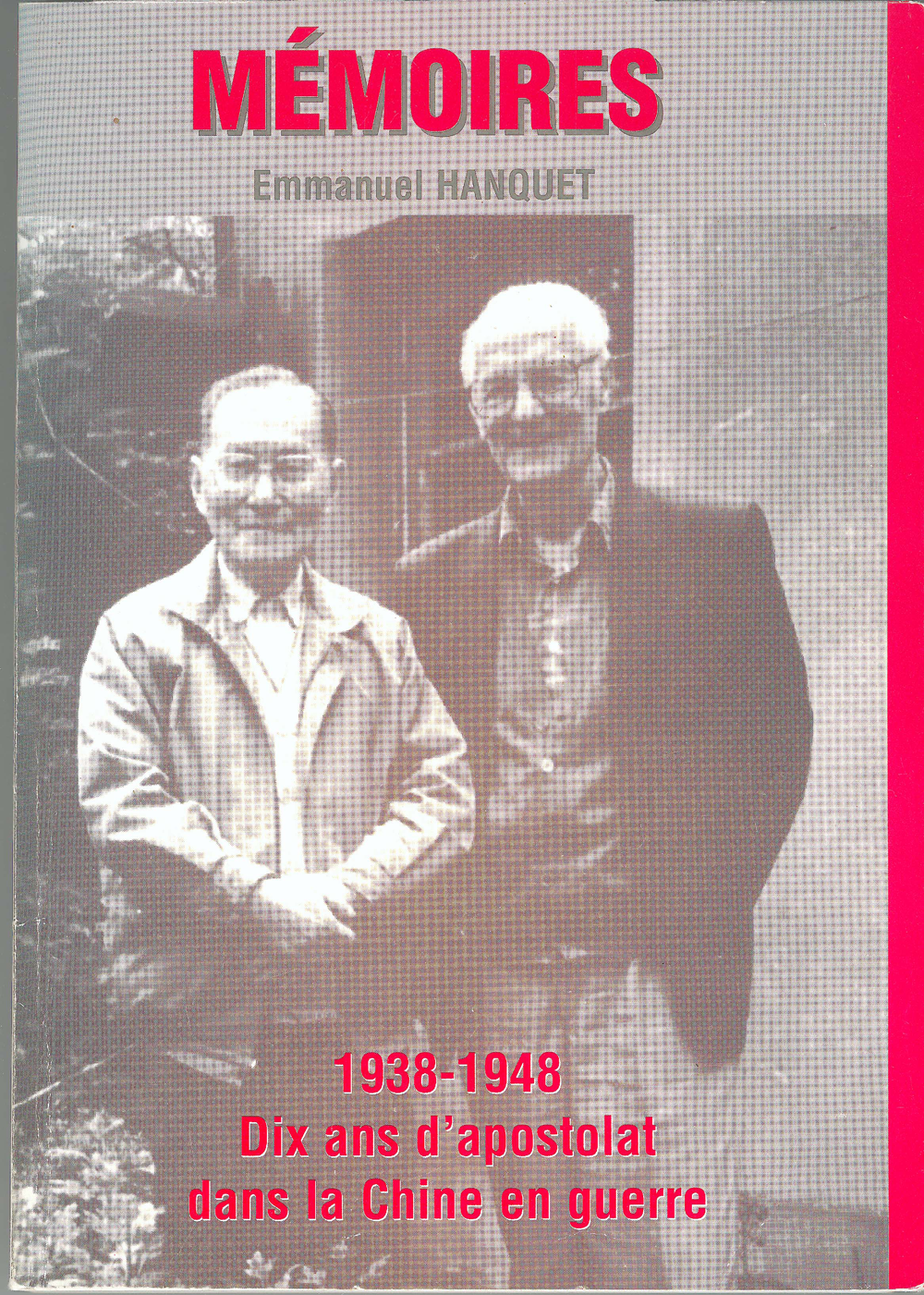

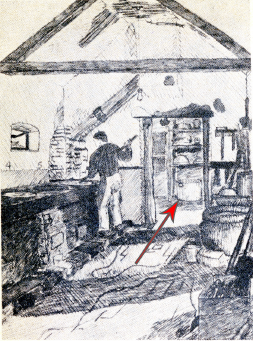

He didn’t say whether it was in the morning or in the afternoon shift but he was chef cook in Kitchen number one and they were preparing a great quantity of boiling stew in a very large cooking pot placed on top of the red-hot burning stove as the one on the image of the kitchen #1. The red arrow points towards the marmite mentioned here. The morning stokers — he told me — had just fed the fires with a new provision of wood.

As Father Hanquet was conscientiously mixing the contents of the boiling stew by stretching his whole body to reach the summit of the large cooking pot he unconsciously leaned a bit too close against the furnace and did not immediately feel that his trousers were burning.

Well, his pants were on fire and when his kitchen mates finally extinguished their flaming chef cook there was evident damage on the most sensitive parts of his body.

He was taken in express — to the hospital where the doctors declared that his family jewels and surroundings were badly burnt and that he would have to stay in hospital for a certain time.

Needless to mention that he was replaced as “chef” in Kitchen number one.

Of course, all his fellow priests had a good laugh at this momentary handicap — .

Once his health re-established and with another pair of trousers Father Hanquet did not return to Kitchen number one. Instead, he had to cut wood for the kitchen fires which he did with so much energy that he broke the axe’s wooden handle. He got it fixed with an iron handle instead.

He missed the company of his cooking mates as his woodcuting chore was to be done all alone.

Anyway, he had a good chuckle when telling me that story.

Ha! Ha! Ha!

He loved to laugh when telling stories about Weihsien !

[excerpts] ...

Everything had to be sorted out.

For example, in No. 1 kitchen where I had volunteered to work our only equipment was six huge cast-iron cauldrons each heated by its own stove. We had to improvise lids using planks and carve great spatulas out of good wood in order to stir the grub as it was cooking…

For example, in No. 1 kitchen where I had volunteered to work our only equipment was six huge cast-iron cauldrons each heated by its own stove. We had to improvise lids using planks and carve great spatulas out of good wood in order to stir the grub as it was cooking…

[excerpts] ...

All available skills were harnessed: carpenter, bricklayer, tinsmith, baker, cook, teacher, seamstress, soapmaker[!], instrumentalist, etc

As for me, I offered my services to the kitchen as junior kitchen-hand No. 6. It was a good way of ensuring that you got at least some food! Dare I admit that I hardly lost any weight in camp and that I ended my career in the kitchen as head cook for six hundred souls?! I was proud of my young and active team of six who never complained about the hard graft. My right hand man was one Zimmerman, a Jewish American, who was a far better cook than I was. He had a Russian wife who was a source of good ideas. For example, we were renowned for our Tabasco sauce which was a mixture of raw minced turnip, pili-pili and red peppers which you could sometimes get from the canteen.

With these ingredients we would make a sort of sauce that took the skin off your throat but which had the merit of giving some taste to dishes which otherwise had none.

We used to put up our menus when it was our turn to cook - every third day: it was our way of lifting the spirits of the internees. But one day we realized that a Japanese guard would come and conscientiously copy down our menus for sending to… the Geneva Convention!

That put an end to our gastro-literary efforts!!

The young people had to work too. Their studies came first. We had organized for them two teaching regimes, American and British. So they went to school every day in the makeshift classrooms. But they were also required to pump water for two hours a day. That was the wearisome task for many of the rest of us too, as there were four water towers in the camp from which water had to be distributed to the kitchens and the showers. Otherwise you got your own water in jugs. The latrines were inevitably very primitive, and had a system of pedals such as used to be found in French railway stations. They were well kept. Oddly enough they were often the responsibility of the Fathers , of us missionaries, although we were few in number! But I have to say that our willingness to undertake this task was not entirely disinterested. The latrines were one of the few places you could meet Chinese, who came to empty them, and we developed good relationship with them with an eye to planning escapes.

To complete the account of the types of work I chose to do or found myself obliged to do during those thirty months I would tell you that I was also a noodlemaker, a woodcutter and, last but not least, a butcher.

That was the work I most liked, though you had to be very careful not to get infected fingers. Much of the meat was very poor, but we tried to rescue enough to make so-called hamburgers or stews, though they were mainly of potato.

And choosing the job of butcher was also calculated, since there too you could meet Chinese people as they came to deliver their merchandise.

Occasionally, and fleetingly, you found yourself alone with one of them and that gave you a chance to exchange news.

That was how I learned of the Japanese military collapse…

I hastened to pass on the amazing news to the other prisoners. I remember that some English friends whom I had told of the rumour invited me to take a thimble of alcohol to celebrate the glad tidings. But ‘Beware lest you be wrong’ they said to me ‘for if you are you will have to buy us a whole bottle’.

In the event I had no cause to regret my optimism.

etc.

[excerpts] ...

The White Elephant Shop

The needs of everyday camp life made you ingenious and resourceful. Some internees had managed to bring into camp in their baggage more than they needed. Others, in contrast lacked everything. I remember a silver tea service which was sold for a few kilos of sugar to the king of the black market, a certain Goyas, who arrived late in camp but who was preceded by his reputation as a notorious fraudster.

Goyas had the tea service melted down into ingots that could be used for currency exchange.

To facilitate exchanges of goods between prisoners the camp committee had the idea of opening a shop where clothes and other items, ticketed with a price, could be exchanged. For example, you could buy some winter garment so long as you brought along another object of the same value, or paid for it with the Japanese yuans which were meted out sparingly to us and referred to as comfort money . This was in the form of a loan which had to be repaid to our governments at the end of the war!

The White Elephant shop ran for about a year, until there was practically nothing left to turn into cash or to exchange.

Cigarettes were another source of currency, at least for the non-smokers. We were entitled to a pack of a hundred cigarettes once a month from the canteen. That was not nearly enough for the serious smokers, but it was handy for those who could use them for barter.

The children from Chefoo school – a protestant school which had arrived in camp complete with staff – used them to augment their bread ration, which was never enough to satisfy their hungry young stomachs.

[excerpts] ...

The Black Market…

In the early days of our internment, the Japanese did little to stop us communicating with the outside world. Apart from the perimeter wall and the barbed wire beyond there were only the watchtowers – or perimeter towers – which occurred on the wall wherever there was a corner.

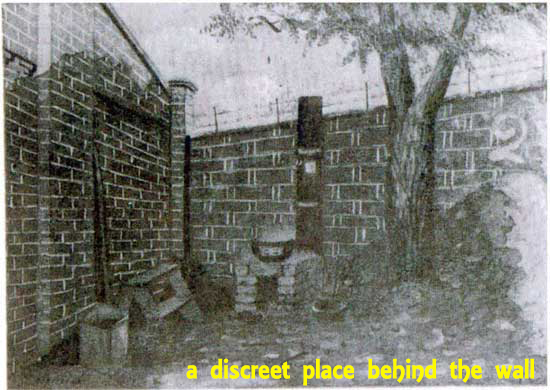

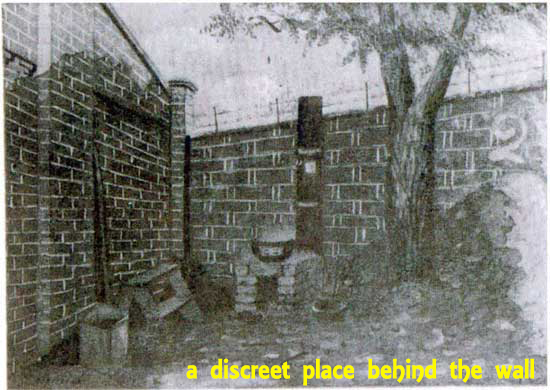

There was however an exception: the camp was not an exact rectangle, and there were blind spots including one section of wall which was hard to see from a watchtower.

There was however an exception: the camp was not an exact rectangle, and there were blind spots including one section of wall which was hard to see from a watchtower.

The Trappist monks’ accommodation was near to this stretch of wall and Father Scanlon had made it the HQ of the black market, with the wall itself serving as the … counter.

The Chinese outside the wall had been quick to take advantage of this feature of the wall to come - by day - and prowl around, offering to sell things, mainly sugar and eggs.

At first the orders were delivered over the wall by Chinese who climbed over the barbed wire, but the day came when the wire was electrified and one of the traders was electrocuted and left hanging dead on the barbed wire.

The black market was a pretty risky business…

Nevertheless Father Scanlan continued unfazed with his little egg trade and was thus a great help to those families with children. He had found another discreet way to take delivery of his egg orders: a length of guttering which served to carry away rainwater.

When the weather was dry the eggs arrived one by one along this guttering, despatched discreetly by a Chinese posted on the other side of the wall.

However, Father Scanlan was being closely watched. Already a guard had once come upon him pacing the wall at nightfall, breviary in hand. He had been challenged:

- ‘What are you doing here?’

- ‘As you can see, I am reading my breviary.’

– ‘Impossible, it is far too dark’ retorts the guard.

– ‘Yes, but I know it by heart’ replies Father Scanlan.

Alas, what he was up to was stumbled on one day when he was sitting on a stool with his Trappist robes covering the stool below which the eggs were gently rolling out.

Up comes a guard. No chance of warning off the Chinese who continues to send along the eggs. One unfortunate egg, more fragile than the others, comes and cracks open against the others.

The sound alerts the guard who uncovers the ploy.

Father Scanlon was taken to the cells which were close by the building where the guards lived.

The Father, as a good Trappist, was untroubled by solitary confinement and would sing the different hours of the breviary at the top of his voice.

This drove the Japanese mad, and after trying him in another cell they decided to send him back to us.

That was the end of the black market…

[excerpts] ...

Have I ever been afraid in camp ?

As an answer to Mary Previte’s question, I believe that once or twice, I feared reprisals from the Japanese guards, and for that, yes, I was afraid that something nasty could have happened to me.

I specially remember this little adventure that finally had a favourable outcome though it could have sent me directly to jail for several days if ever I got caught red handed.

You all know of the food shortage problems and how much we suffered from the lack of primary food necessities such as, oil, eggs and sugar. Sugar was in great demand by the children’s parents who tried getting small provisions through the black market.

We, adults, were quite accustomed to the shortage of sugar. That is the reason why my friend C.B. made an inquiry to find out where exactly the Japanese stored the bags of sugar. In precisely which house in the compound it was kept, and when he finally had this valuable information, he decided to act immediately.

To act quickly, he needed an accomplice to watch our side of the compound wall while he was on the other side, in the Japanese quarters, rigorously reserved to the Japanese and them alone. Another problem to resolve, was the hiding of the precious sugar before transferring it into little bags for the few families who had asked for it.

Just outside our quarters, (bloc n°56) there was, in a small garden, a dry well which must have been dug in the past years for keeping vegetables during the winters. That was an ideal place for our sugar. Safe and discreet.

So, on one autumn evening when darkness fell around us, my friend made a rendezvous with me near the wall, just behind the Japanese accommodations. I was watching while he was on the other side. I walked to and fro, trying to make believe I was just a passer by.

After what seemed to be a long time, I saw a head emerging just above the wall, and all of a sudden I had in my arms, a whole bag of sugar of 10 kilos. It was quickly hidden in an old jacket and off we went to bloc n°56 to hide, the old jacket with the sugar in the well.

We didn’t meet anybody on the way. The following days, C.B. made a few nightly visits to our little garden, taking in tiny bags, small amounts of the precious sugar to those who needed it.

I would like to add a comment about “scrounging” in camp. You can only imagine how we felt, as civilians, rounded-up, imprisoned behind walls and guarded by armed Japanese soldiers.

To pinch away something from them was not an act of stealing, it was just a correct return of what they had taken from us.

***

[excerpts] ...

[further reading] ...

copy/paste this URL into your Internet browser:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/hanquet/book/Memoires-TotaleUK-web.pdf

#

... and here is the true story of how Father Emmanuel Hanquet’s adventure in Kitchen #1 finally ended:

... it is as he told it to me at his home in Louvain-la-Neuve — when he was still alive and healthy !

He didn’t say whether it was in the morning or in the afternoon shift but he was chef cook in Kitchen number one and they were preparing a great quantity of boiling stew in a very large cooking pot placed on top of the red-hot burning stove as the one on the image of the kitchen #1. The red arrow points towards the marmite mentioned here. The morning stokers — he told me — had just fed the fires with a new provision of wood.

As Father Hanquet was conscientiously mixing the contents of the boiling stew by stretching his whole body to reach the summit of the large cooking pot he unconsciously leaned a bit too close against the furnace and did not immediately feel that his trousers were burning.

Well, his pants were on fire and when his kitchen mates finally extinguished their flaming chef cook there was evident damage on the most sensitive parts of his body.

He was taken in express — to the hospital where the doctors declared that his family jewels and surroundings were badly burnt and that he would have to stay in hospital for a certain time.

Needless to mention that he was replaced as “chef” in Kitchen number one.

Of course, all his fellow priests had a good laugh at this momentary handicap — .

Once his health re-established and with another pair of trousers Father Hanquet did not return to Kitchen number one. Instead, he had to cut wood for the kitchen fires which he did with so much energy that he broke the axe’s wooden handle. He got it fixed with an iron handle instead.

He missed the company of his cooking mates as his woodcuting chore was to be done all alone.

Anyway, he had a good chuckle when telling me that story.

Ha! Ha! Ha!

He loved to laugh when telling stories about Weihsien !

Everything had to be sorted out.

[excerpts] ...

All available skills were harnessed: carpenter, bricklayer, tinsmith, baker, cook, teacher, seamstress, soapmaker[!], instrumentalist, etc

As for me, I offered my services to the kitchen as junior kitchen-hand No. 6. It was a good way of ensuring that you got at least some food! Dare I admit that I hardly lost any weight in camp and that I ended my career in the kitchen as head cook for six hundred souls?! I was proud of my young and active team of six who never complained about the hard graft. My right hand man was one Zimmerman, a Jewish American, who was a far better cook than I was. He had a Russian wife who was a source of good ideas. For example, we were renowned for our Tabasco sauce which was a mixture of raw minced turnip, pili-pili and red peppers which you could sometimes get from the canteen.

With these ingredients we would make a sort of sauce that took the skin off your throat but which had the merit of giving some taste to dishes which otherwise had none.

We used to put up our menus when it was our turn to cook - every third day: it was our way of lifting the spirits of the internees. But one day we realized that a Japanese guard would come and conscientiously copy down our menus for sending to… the Geneva Convention!

That put an end to our gastro-literary efforts!!

The young people had to work too. Their studies came first. We had organized for them two teaching regimes, American and British. So they went to school every day in the makeshift classrooms. But they were also required to pump water for two hours a day. That was the wearisome task for many of the rest of us too, as there were four water towers in the camp from which water had to be distributed to the kitchens and the showers. Otherwise you got your own water in jugs. The latrines were inevitably very primitive, and had a system of pedals such as used to be found in French railway stations. They were well kept. Oddly enough they were often the responsibility of the Fathers , of us missionaries, although we were few in number! But I have to say that our willingness to undertake this task was not entirely disinterested. The latrines were one of the few places you could meet Chinese, who came to empty them, and we developed good relationship with them with an eye to planning escapes.

To complete the account of the types of work I chose to do or found myself obliged to do during those thirty months I would tell you that I was also a noodlemaker, a woodcutter and, last but not least, a butcher.

That was the work I most liked, though you had to be very careful not to get infected fingers. Much of the meat was very poor, but we tried to rescue enough to make so-called hamburgers or stews, though they were mainly of potato.

And choosing the job of butcher was also calculated, since there too you could meet Chinese people as they came to deliver their merchandise.

Occasionally, and fleetingly, you found yourself alone with one of them and that gave you a chance to exchange news.

That was how I learned of the Japanese military collapse…

I hastened to pass on the amazing news to the other prisoners. I remember that some English friends whom I had told of the rumour invited me to take a thimble of alcohol to celebrate the glad tidings. But ‘Beware lest you be wrong’ they said to me ‘for if you are you will have to buy us a whole bottle’.

In the event I had no cause to regret my optimism.

etc.

Goyas had the tea service melted down into ingots that could be used for currency exchange.

To facilitate exchanges of goods between prisoners the camp committee had the idea of opening a shop where clothes and other items, ticketed with a price, could be exchanged. For example, you could buy some winter garment so long as you brought along another object of the same value, or paid for it with the Japanese yuans which were meted out sparingly to us and referred to as comfort money . This was in the form of a loan which had to be repaid to our governments at the end of the war!

The White Elephant shop ran for about a year, until there was practically nothing left to turn into cash or to exchange. Cigarettes were another source of currency, at least for the non-smokers. We were entitled to a pack of a hundred cigarettes once a month from the canteen. That was not nearly enough for the serious smokers, but it was handy for those who could use them for barter.

The children from Chefoo school – a protestant school which had arrived in camp complete with staff – used them to augment their bread ration, which was never enough to satisfy their hungry young stomachs.

The Trappist monks’ accommodation was near to this stretch of wall and Father Scanlon had made it the HQ of the black market, with the wall itself serving as the … counter.

The Chinese outside the wall had been quick to take advantage of this feature of the wall to come - by day - and prowl around, offering to sell things, mainly sugar and eggs.

At first the orders were delivered over the wall by Chinese who climbed over the barbed wire, but the day came when the wire was electrified and one of the traders was electrocuted and left hanging dead on the barbed wire.

The black market was a pretty risky business…

Nevertheless Father Scanlan continued unfazed with his little egg trade and was thus a great help to those families with children. He had found another discreet way to take delivery of his egg orders: a length of guttering which served to carry away rainwater. When the weather was dry the eggs arrived one by one along this guttering, despatched discreetly by a Chinese posted on the other side of the wall.

However, Father Scanlan was being closely watched. Already a guard had once come upon him pacing the wall at nightfall, breviary in hand. He had been challenged:

- ‘What are you doing here?’

- ‘As you can see, I am reading my breviary.’

– ‘Impossible, it is far too dark’ retorts the guard.

– ‘Yes, but I know it by heart’ replies Father Scanlan.

Alas, what he was up to was stumbled on one day when he was sitting on a stool with his Trappist robes covering the stool below which the eggs were gently rolling out.

Up comes a guard. No chance of warning off the Chinese who continues to send along the eggs. One unfortunate egg, more fragile than the others, comes and cracks open against the others.

The sound alerts the guard who uncovers the ploy.

Father Scanlon was taken to the cells which were close by the building where the guards lived.

The Father, as a good Trappist, was untroubled by solitary confinement and would sing the different hours of the breviary at the top of his voice.

This drove the Japanese mad, and after trying him in another cell they decided to send him back to us.

That was the end of the black market…

I specially remember this little adventure that finally had a favourable outcome though it could have sent me directly to jail for several days if ever I got caught red handed.

You all know of the food shortage problems and how much we suffered from the lack of primary food necessities such as, oil, eggs and sugar. Sugar was in great demand by the children’s parents who tried getting small provisions through the black market.

We, adults, were quite accustomed to the shortage of sugar. That is the reason why my friend C.B. made an inquiry to find out where exactly the Japanese stored the bags of sugar. In precisely which house in the compound it was kept, and when he finally had this valuable information, he decided to act immediately.

To act quickly, he needed an accomplice to watch our side of the compound wall while he was on the other side, in the Japanese quarters, rigorously reserved to the Japanese and them alone. Another problem to resolve, was the hiding of the precious sugar before transferring it into little bags for the few families who had asked for it.

Just outside our quarters, (bloc n°56) there was, in a small garden, a dry well which must have been dug in the past years for keeping vegetables during the winters. That was an ideal place for our sugar. Safe and discreet.

So, on one autumn evening when darkness fell around us, my friend made a rendezvous with me near the wall, just behind the Japanese accommodations. I was watching while he was on the other side. I walked to and fro, trying to make believe I was just a passer by.

After what seemed to be a long time, I saw a head emerging just above the wall, and all of a sudden I had in my arms, a whole bag of sugar of 10 kilos. It was quickly hidden in an old jacket and off we went to bloc n°56 to hide, the old jacket with the sugar in the well.

We didn’t meet anybody on the way. The following days, C.B. made a few nightly visits to our little garden, taking in tiny bags, small amounts of the precious sugar to those who needed it.

I would like to add a comment about “scrounging” in camp. You can only imagine how we felt, as civilians, rounded-up, imprisoned behind walls and guarded by armed Japanese soldiers.

To pinch away something from them was not an act of stealing, it was just a correct return of what they had taken from us.

***

[excerpts] ...