- by Langdon Gilkey

Chapter 4

[excerpts] ...

in The Kitchen ...

[...]

It was at this point that I became an assistant cook, hardly knowing then how to boil an egg. My boss was a gay and talented bachelor named Edwin Parker. With graying hair and a round face, he had been a curio and art dealer from Peking. Edwin knew how to cook, but he hated to boss anybody or to organize his meals too carefully. As a result, our life was filled with confusion and laughter, but also with frequent culinary triumphs. My job was to keep the pans and cauldrons clean, to cut up meat, stir soups and stews, fry leeks, and braise meat—in other words, all the routine chores, while Edwin, as chef, planned, directed, and seasoned the menu.

Since we both wanted to live on as good food as possible, we worked hard. Although we were not the best of the three cooking teams in our kitchen (each one worked every third day), ours came to have a growing favorable reputation among our ordinarily disgruntled diners. As the first winter closed in, I liked to come to work before dawn, to watch our stoker (an insurance man from Peking) coax the fires into life under the cauldrons, to start cooking the cereal in the large guo (caldron), and to fry people’s black-market eggs on our improvised hot plate. Then, after spending the rest of the day preparing lunch and supper, I would return in the dark to the hospital and an evening with Alice, tired but full of the satisfaction of one who has worked with his muscles all day.

It was, therefore, a severe blow when word came from the Japanese that on January first (1944) we would have to move out of Kitchen III into one of the other two large kitchens. Each of these was filled with what seemed to us to be immense crowds of unfamiliar people, and from all reports, enjoyed a notoriously bad spirit and worse food. But since the Japanese insisted—they intended to house the newly arriving Italians in that section of the camp—we had no choice but to leave Kitchen III.

As luck would have it, my first day of duty in the new place, Kitchen I, came on New Year’s morning. I had never been inside the place—so much vaster than our intimate kitchen with two small guos and a team made up of only two cooks—and so I hardly knew my way around its vast interior. What made matters worse was that the night before there had been a very gay dance in the Tientsin kitchen (Kitchen II) to which Alice and I had gone and, reasonably enough, we had not got in until about 4 A.M.

So, sleepy, headachy, and angry, I groped my way, about 6 A.M., into the unknown recesses of Kitchen I. It was a cold, damp morning; the newly made fires created such thick steam that I could only dimly discern the long line of huge guos with many strange figures bending over them. Gradually, as the steam cleared, I became aware that the voice giving sharp orders Belonged to the boss cook, and the feet I kept seeing under the rising steam to the six helpers on the cooking team; also I realized that I was helping to cook cereal and that others were beginning the preparation for lunchtime stew.

It took little longer to grasp that no one there was much concerned about the quality of the food we made, and no one was eager to work more than absolutely necessary. McDaniel, the boss, was a nice enough guy in a rough, indifferent, and lazy way; but we knew that his sharp-tongued wife told him what to cook. He used to run home in the middle of most afternoons because he had forgotten what she had told him about supper! Beyond carrying out these orders, he knew little and cared less about cooking. For my first two months there, I felt frustrated about the job we were doing. There must be some way, thought I, of pepping things up and turning out better food. And so I began to look around for others who might feel the same way, but who, unlike myself, knew how to cook.

Gradually as I worked in that kitchen and learned to know it, its strangeness and size diminished. I even found myself enjoying my hours every third day on duty. There was a sunny courtyard just off the main kitchen, and on good days, when we could prepare the food for stews out there and eat our lunch at the big table, there was an atmosphere of rough, ribald fun that I heartily enjoyed. As this sense of at-homeness grew, I found that the functioning of the kitchen as a complex of coordinated activities came to interest me—for it really was a remarkable organization.

This organization began outside the kitchen when food supplies were brought into camp on carts by Chinese. They were distributed by the Supplies Committee proportionally to each of the two main kitchens. Then the supplies gang carried them in wooden crates to the kitchens—vegetables to the vegetable room and meat to the butchery. At this point the two cooks for the following day looked glumly over the meager supplies they had been given for their eight hundred customers, racked their brains for some new ideas for a menu, and then told the vegetable captains and the butchers what they wanted in the raw preparation of these supplies.

This organization began outside the kitchen when food supplies were brought into camp on carts by Chinese. They were distributed by the Supplies Committee proportionally to each of the two main kitchens. Then the supplies gang carried them in wooden crates to the kitchens—vegetables to the vegetable room and meat to the butchery. At this point the two cooks for the following day looked glumly over the meager supplies they had been given for their eight hundred customers, racked their brains for some new ideas for a menu, and then told the vegetable captains and the butchers what they wanted in the raw preparation of these supplies.

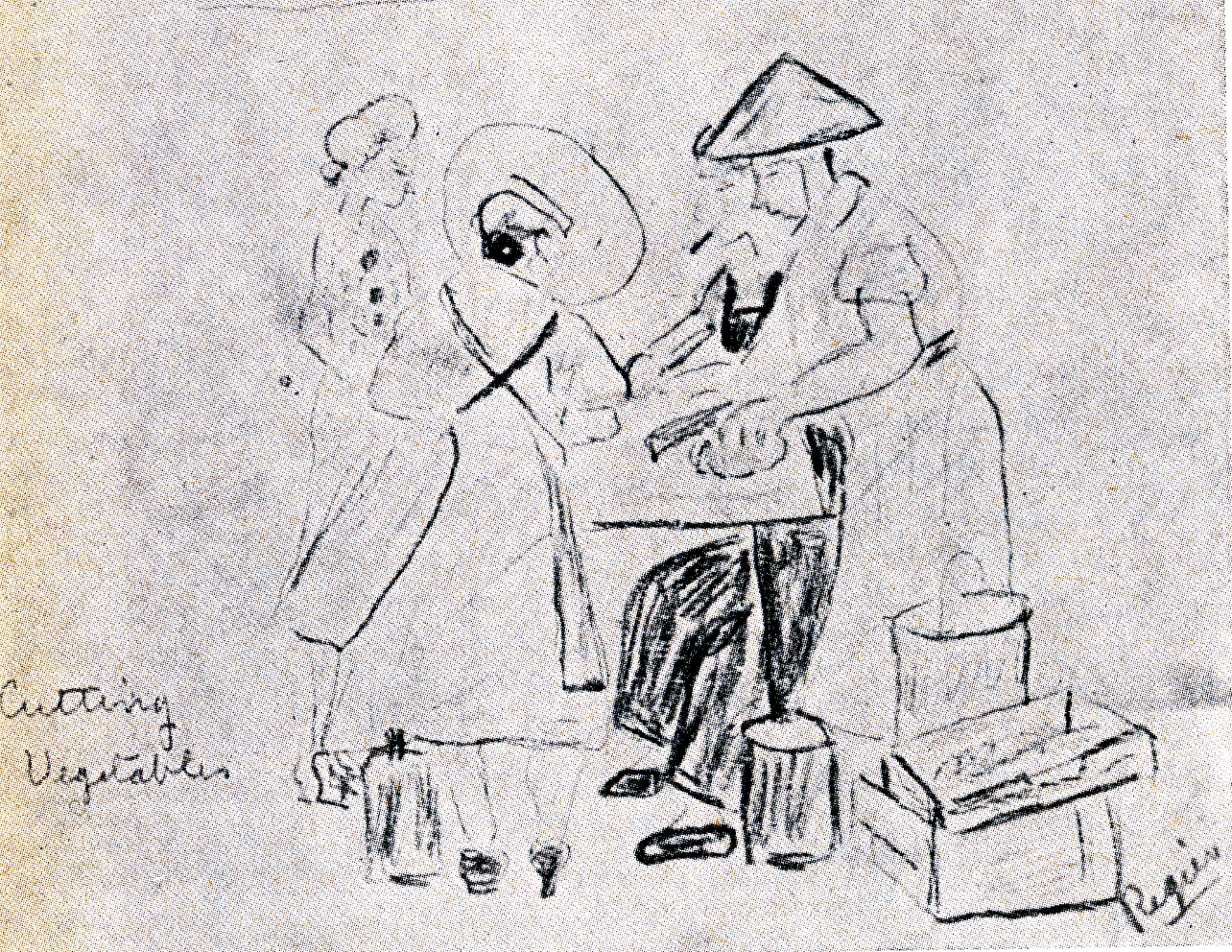

That same afternoon and into the next morning, the two butchers sliced, cubed, or ground the meat (this would be the winter procedure; they boiled it in summer in order to ensure its keeping at least over night without refrigeration). Teams of some fifteen to twenty women diced carrots, peeled potatoes, and chopped cabbage, while middle-aged men helped them by carrying the vegetable baskets around and by cleaning the produce in a pair of old bathtubs taken from the residences in the “out of bounds” section of the compound.

The next day the two cooks and five helpers came on duty about 5 A.M. They prepared breakfast cereal if there was any, and then lunch and supper for that day. A pan washer on my shift (actually a scholar of Chinese literature, and now a professor at Cornell University) washed the containers we used in preparing the food and from which we ladled out the dinner. Then women servers distributed the food to the waiting lines collecting food for our eight hundred people. They were checked and watched over by elderly men counters who made sure no one came in twice, and kept tabs on how fast the food was running out.

Girls then passed tea—if there was any—around the tables in the dining room. Men tea servers poured it into flasks for the majority who, being families preferred to collect their food in covered containers and to eat it en famille in their rooms. Near the serving tables was the bread room where five or six older men sliced two hundred loaves of bread daily and distributed to each his ration. And finally, two teams of women dishwashers cleaned up the dishes after the meal of those who ate in the dining hall. All of these groups got time off depending on the hours and heaviness of their work.

Cooking food and boiling water, however, required heat. For this purpose, coal and wood were brought to the kitchen yard from the supply house in carts. In our yard two men were always chopping wood while others molded bricks out of the coal dust that made up most of our usual coal issue. Two stokers got up the fires and tended them, one in the cooking area and the other where water was boiled for drinking. Stoking was a job which called for great skill since the coal was poor and the cooks extremely demanding about the level of heat they had to have under their precious stews.

To keep this intricate organization running smoothly, there was at first only an informal structure, headed by the manager of the kitchen, who seemed to do everything, and two women storekeepers. The latter kept an eye on our small stores of sugar and oil; also they purchased raw ginger, spices, and dried fruits when they were available in the canteen; and generally functioned as advisers of the manager on his many problems.

One morning my career as a kitchen helper was rudely interrupted by a fairly serious accident. It was a raw February day in 1944. Since there was nothing much to do in the cooking line, some of us, spurred on by the complaints of our more sensitive diners, decided to clean up the south kitchen where water was boiled for drinking. Our kitchens were terribly dirty; soot from the fires covered ceiling and walls; grease was inevitably added to this layer on the cauldron tops; and the floor combined all this with its own tracked-in mud.

Cleaning meant trying, with brooms and cloths, to get as much of this dirt and soot off the walls, ceiling, and pipes as possible.

Along the wall above the top of the cauldrons was a chimney ledge that protruded about five inches. Thinking that it was wide enough to stand on, I clambered up. I had not been there twenty seconds when I felt myself losing my balance, and instinctively I stepped back—into a cauldron of boiling water. “Boy, that’s hot,” I half-said to myself, and in the same instant I was across the room. I can recall no conscious mental command telling me to jump as I found myself leaping out of that cauldron. In fact, I catapulted out so fast that my working mate only saw me crashing into the wall opposite and thought, he admitted later, that I had simply gone mad. Next I found myself hopping up and down as fast as I could. Then I sat down and eased off my shoes and socks to see what had happened to my feet.

I had no idea I was badly burned until, taking the sock off my right ankle and foot, I found the skin coming off with it. By that time the boss cook had come over from the north kitchen. With one look at my now skinless ankles, he gave quick orders to take me to the hospital immediately. Two burly fellows on the shift made a chair with their arms and trundled me off. It was not until we got out in the air that I became conscious of real pain. To be sure, when I was hopping up and down, my feet stung; but this was worse. From that time on for about five hours, my burns hurt a lot.

The doctors in the hospital did a wonderful job. A British doctor for the Kailon Mining Company put picric acid on the bandages and did not take them off for about ten days. Due to the sulphanilamide that was smuggled into camp through the guerrillas, I was able to avoid infection. When the bandages finally came off, new skin had grown almost everywhere. Within three weeks, I was hobbling around. In six months all that was left to show of the burn was a rather grim abstract color effect of yellow and magenta.

#

[further reading]

copy/paste this URL into your Internet browser:

https://www.amazon.com/Shantung-Compound

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/BOOK/Gilkey-BOOK(WEB).pdf

#