chapter 2

The Cooke family and me

It is true to say that the most dramatic events in my life occurred after World War II broke out between Japan and the Allied powers largely consisting of the British Empire and Commonwealth and the United States.

However, my family's history before and after those events is relevant to my story.

To explain why my family was in China, let me start my family's story with a summary of the published obituary of my paternal great-grandfather, James Edward Cooke – printed in the North China Herald [2] in 1881.

[2] North China Herald and Supreme Court and Consular Gazette published Shanghai March 1, 1881. Death announcement is given as February 20, 1881 at Ningpo. Notification of death is at front page, obituary is at page 192. The obituary article is similar in style and content to a report carried in The N.-C. Daily News published March 2, 1881. The N.-C. Daily News of February 25,1881 carried a report of Cooke's burial. Cooke's Death certificate obtained from the Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (London) confirm date of death. Bradbury family collection.

James Edward Cooke was born in Jamaica, the son of a planter. He was educated in Bristol, England, and he joined the British Royal Navy after school and served for an unknown period. He left the Royal Navy and at the age of 22 became master of a vessel owned by King & Co, an African Gold Coast exploration company.

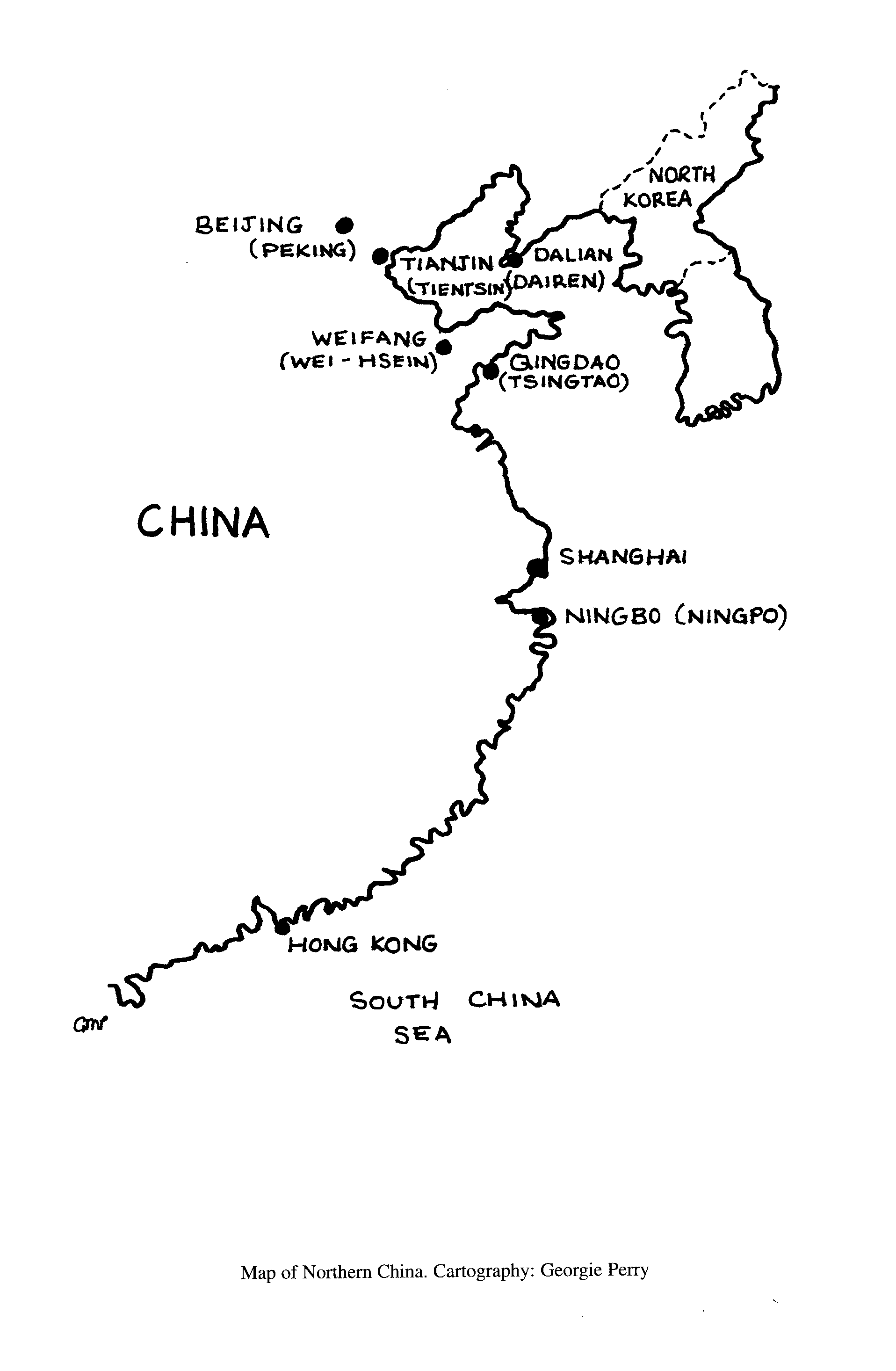

Cooke arrived in Ningpo (now called Ningbo) – a foreign trading port near the mouth of the Yung River in eastern China's Chekiang province (now called Zhejiang province) – in 1861. He was mate of the British barque Alice.

Shortly after the Alice's arrival, the barque's captain was murdered ashore by some of his crew and Cooke became the temporary master. He took the vessel to Hong Kong and left her. At the time Cooke left the Alice civil conflicts were raging in China. Fighting on the governing Manchu dynasty side were Chinese, British and French-led forces.

The conflicts occurred in the aftermath of the ratification of the Treaty of Tientsin (1858) which formally ended the Opium Wars in China. The First Opium War between Britain and China started in 1839. It sharply intensified after opium from British India – which was brought to China to pay for Chinese fine porcelains, silks and tea – was publicly burned by the Chinese in 1840. The Chinese authorities burned the opium because they were deeply concerned by the havoc narcotic opium addiction was having on the people. The burning followed persistent British abstinence in not obeying a Chinese ban on opium imports to China made in 1800. A separate concern of the Chinese was that Chinese payments for banned opium imports were draining China's silver standard-based economy.

The conflicts occurred in the aftermath of the ratification of the Treaty of Tientsin (1858) which formally ended the Opium Wars in China. The First Opium War between Britain and China started in 1839. It sharply intensified after opium from British India – which was brought to China to pay for Chinese fine porcelains, silks and tea – was publicly burned by the Chinese in 1840. The Chinese authorities burned the opium because they were deeply concerned by the havoc narcotic opium addiction was having on the people. The burning followed persistent British abstinence in not obeying a Chinese ban on opium imports to China made in 1800. A separate concern of the Chinese was that Chinese payments for banned opium imports were draining China's silver standard-based economy.

The British deliberately ran mainly Indian-grown opium cargoes into China so they could earn the Chinese silver to pay for Chinese goods which were subsequently exported by the British world wide.

The British succeeded in winning the First Opium War in 1842. As the prize for that victory Britain demanded that five Chinese ports be opened further for trade and the ceding of Hong Kong to British control – which only ended in the late 1990s.

Following further Chinese resistance to imports of opium and for other strategic reasons, a Second Opium War erupted in 1856 with Britain and France in alliance against China. Following China's defeat, the original Opium War treaty was ratified, giving the European powers more extraterritorial trading privileges in China. [It was not until 1911 that the British Parliament agreed to a ban on opium exports to China.]

Although the Second Opium War ended in 1860, the results of the Opium Wars contributed to a wave of civil conflicts in China. Fuelling the Chinese civil conflicts was widespread Chinese community unrest largely triggered by dissatisfaction with the decaying Manchu regime, concerns about the need for societal reforms, and Chinese nationalist worries about the role increasing numbers of European traders were playing in Chinese communal and economic affairs.

The most serious of these civil conflicts was the Taiping Rebellion which ran from 1850 to 1864. The Taiping (which means great peace in Chinese) rebels were led by Hung Hsiu-chuan who wanted to overthrow the Manchu dynasty and introduce rural reform. There also occurred during roughly the same period a secret society Chinese revolt called the Nianfei from 1853 to 1868 and Muslim rebellions in four provinces during the period 1855-1878.

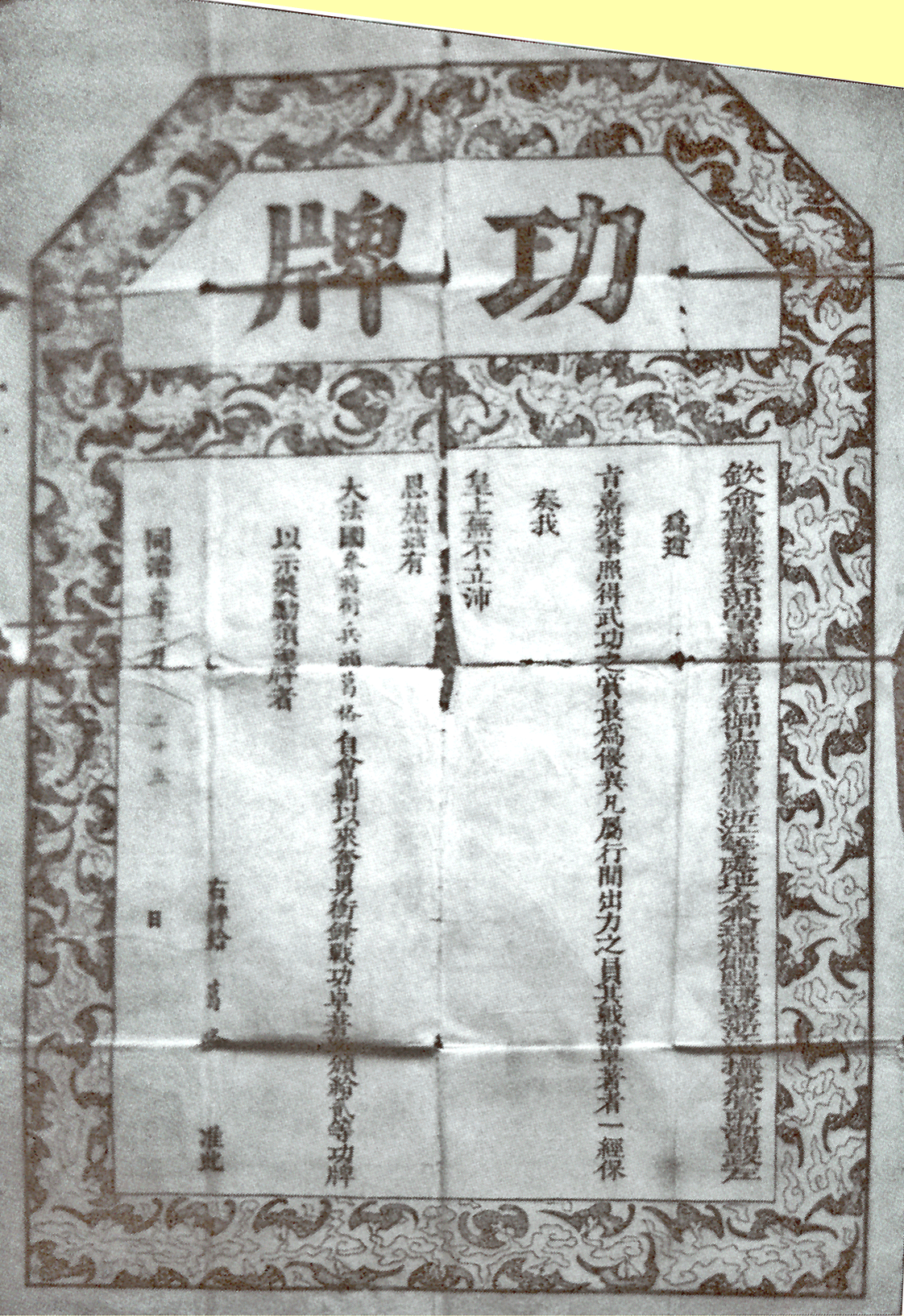

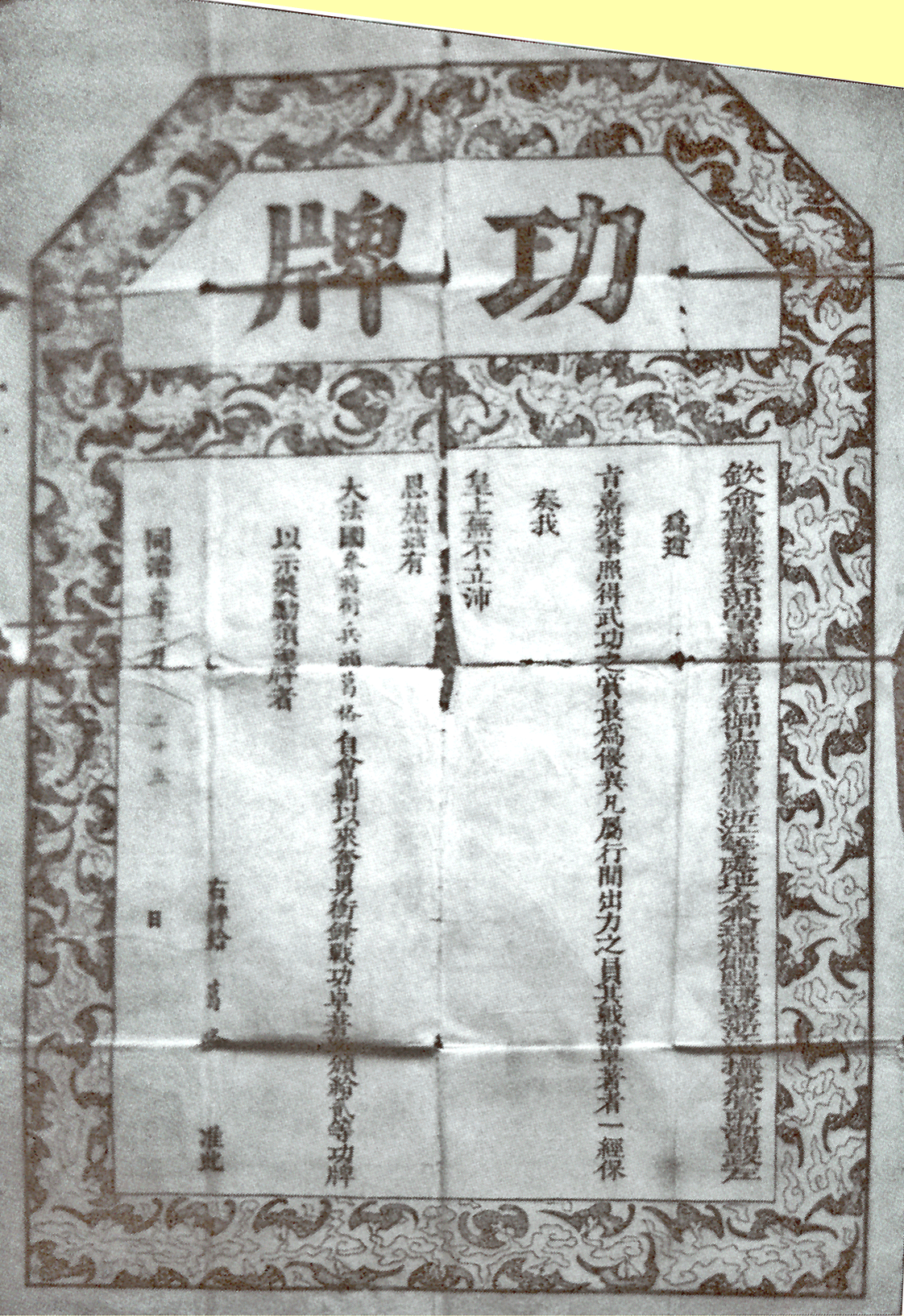

Chinese Imperial honour given Colonel Cooke.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

Because of the great support among many Chinese for the Taiping rebels, the commanding officer of the local Anglo-Imperial Chinese contingent involved in suppressing the Taiping rebels, General Ward [who was an American mercenary soldier], was looking for officers for his army.

General Ward offered great-grandfather Cooke a position as mate of the SS Paoushun. He accepted and later became the vessel's commander.

The obituaries for Cooke say General Ward was impressed by Cooke after forces under Cooke's command destroyed a Taiping artillery battery and successfully fought onshore. Ward persuaded Cooke to go ashore and take command of a company of men fighting the rebels. After many battles resulting in the capture of towns and cities, Cooke – who had been wounded in action – took overall command of General Ward's force after the general was killed in action.

Cooke later fought during the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion under then-Colonel Charles George Gordon (1833-1885) of the British Army who was colloquially called `Chinese Gordon'. Colonel Gordon later became known as `Gordon of Khartoum'.

Following the suppression of the Taiping Rebellion, Cooke was appointed to take command of the Anglo-Chinese Military Contingent in Chekiang province [3] headquartered at Ningpo with the rank of Brigadier [4].

[3] For his services as an officer in the combined British and Imperial Chinese forces during the Taiping Rebellion, Cooke was offered and received a Certificate of Merit under an edict issued by the Imperial Chinese Emperor, T'ung chi. The certificate outlines his battle victories and the wounds he sustained as a member of the Chinese-styled "Ever Victorious Army". Cooke in 1868, through the Ningpo British Consul, had to separately receive the permission of Queen Victoria before he could accept the certificate because of his British citizenship. Certificate and consular letter are in the Cooke family collection.

[4] The newspaper articles (see Footnote 2) referring to Cooke's death refer to him as a Colonel or a Brigadier. On the Marriage certificate obtained from Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (London) for the November 15, 1884 marriage between Cooke's daughter Nellie and Arthur Vere Brown, Cooke's rank is given as Major-General. Bradbury family collection.

He held this position, which required him to superintend policing and military duties, for 16 years. He died at Ningpo from reported cerebral congestion on February 20, 1881. He was interred after a service conducted by the

Church of England (Anglican) Bishop of Shanghai the Right Reverend Bishop G E Moule in Shanghai's new cemetery [5]. Local military units accompanied the cortege and fired a military salute.

[5] The Shanghai Cemetery Register for the 1880s has Cooke listed at Number 999.

Bradbury family collection.

The key benefit of the Opium Wars and the Chinese rebellions to non-Chinese [mainly European] interests as a result of the military actions involving the European nations was the widened concessions granted to foreign nationals that enabled them to live and trade in many parts of China. Because mainly British, French, German, US, Italian, Austrian, Belgian and later Russian and Japanese traders took advantage of the concession trading arrangements, trade with China and the rest of the world quickly grew.

Japan benefited well from China in other ways. It defeated China in a separate war in 1895 and China was forced to yield Korea, Taiwan and the Pescadores (a small group of islands in the Taiwan Strait) to the Japanese.

Under treaty arrangements with China, the foreign citizens living in China were largely immune from Chinese laws but were subject to laws of their own countries. Their children retained the nationalities of their parents' countries even if born in China – provided their births were registered with the relevant diplomatic consul.

Cooke's wife, Mary Sage [6], was a daughter of William Vincent Sage, a shipowner. She may have been part-Chinese but she also was a British subject. They had eight children. John Edward Cooke – one of their sons – was my father's father (my paternal grandfather). John Edward Cooke ran away to sea at the age of about 14 and did not return home for at least five years.

[6] Marriage certificate of February 14, 1881. Copy obtained from Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (London). Certificate shows Cooke was 44 and Sage 30. Bradbury family collection.

On February 12, 1898 after his return to China, John Edward Cooke married [7] Mary Steiglich [8] aged 18. She was born in England of Danish and possibly Chinese extraction. John Edward Cooke became an auctioneer and died in Shanghai on May 26, 1919 [9]. They had six children, one of whom was my father.

[7] Marriage certificate of February 12, 1898 obtained from Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (London). Bradbury family collection..

[8] Marriage Certificate spells her name Steiglich but her Death certificate spells the name as Steglich.

[9] Death certificate of May 26, 1919 obtained from Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages (London). Bradbury family collection.

My father, Edmund James Clarence Cooke, was born in Shanghai on June 16, 1898 and after leaving school worked for Probst Hanbury, a Shanghai trading firm. Later, he became manager of Jardine Matheson, importers and exporters in Tsingtao which is in the Chinese province of Shantung (now called Shandong).

On a visit to Peking (now called Beijing) my father met my mother Vera, who was born in Harbin on July 28, 1908. Mother was then working for a Mr Jernigan, an American business associate of my father. She was a daughter of Vladimir Booriakin, a Russian who had been the Harbin manager of the East Asiatic Bank. Her mother, my maternal grandmother, was Elfreda Booriakina (nee Auer), daughter of a German couple. The ‘a’ is added to the surname or family name of Russian women.

My parents married on July 19, 1927 in Harbin, northern China. I have a photograph of their bridesmaid, Ira Petena. Ira married a Mr Bussy and she later became a Metropolitan Opera (New York) singer.

#

Chinese Imperial honour given Colonel Cooke.

Photograph: Georgie Perry.

Bradbury family collection.

My parents with me as an infant.

Photograph restoration: Advance Photo