March 27, 1943 ...

From the diary directly as written that day. (version 1)

27-3-43

My dear Freda:

I am afraid I have been compelled to allow a week to lapse before writing to you as I have been extremely busy.

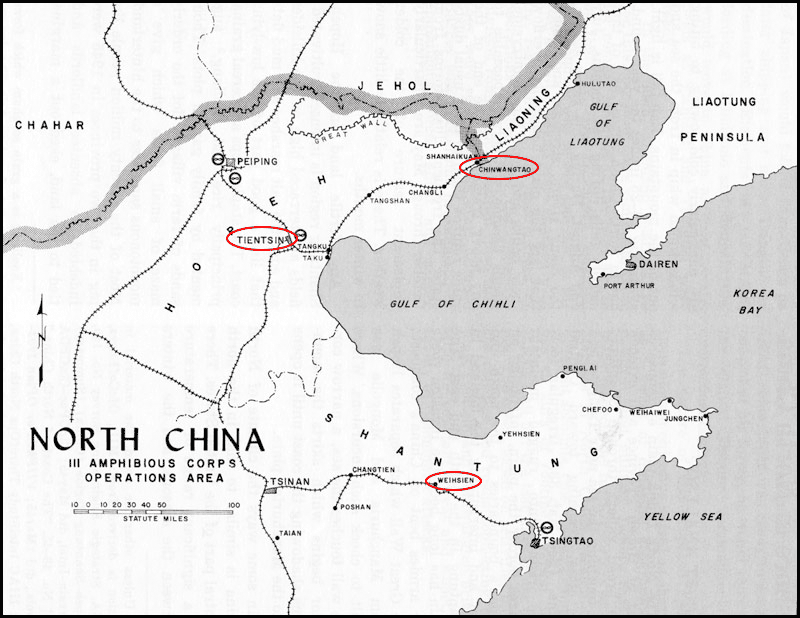

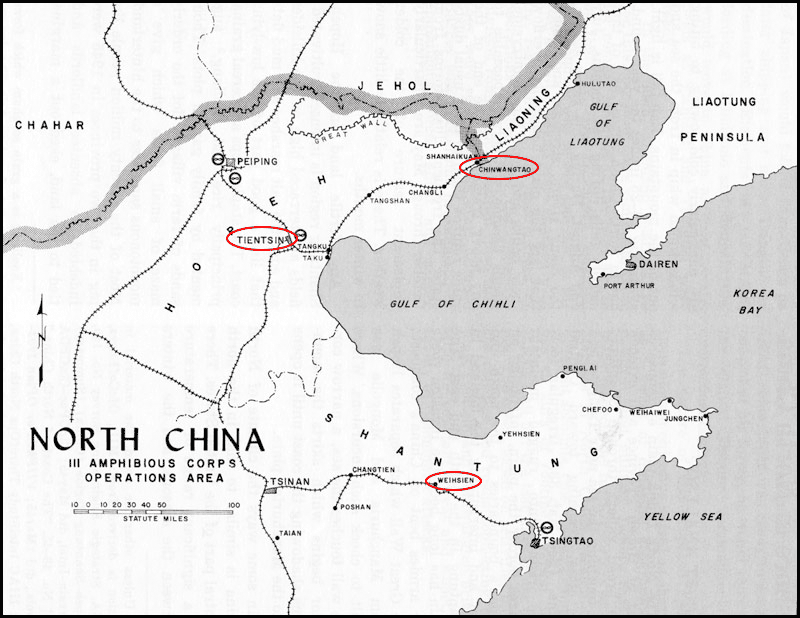

The journey was very long and arduous, the children took it very well. We had terrific receptions at Linsi and Tongshan Stations. At the former Mr Walravens, the Kelseys, and Dufrasne brought a huge quantity of food. Then at Tongshan, Miss Gunn, Miss Hill Murray, Vera Dutoff and Mr Ducuron came with 28 boxes of foodstuff, as well as cigarettes and tinned milk and biscuits.

The Consular Official who accompanied us from CWTao was a particularly nice chap and was extremely helpful. He allowed the foodstuff to be put on board on condition that he examined it to ensure that no booze was brought on. It was only perfunctory as after the first few he said OK.

We changed at Tientsin. Fortunately, we didn’t have to cross over to the Tsuipu Line, our train was shunted back to where we were.

We arrived at Tsinan 2 hrs. late and therefore missed the express connection. Reached Weihsien at 6.30 and were transported to our Camp in busses. The first night we slept in a common dormitory, we had straw mats and some fortunate people had mattress, the crowd who arrived a couple of days before we did, rallied around and brought us blankets and mattresses. Everyone envied Christine as she was carried around in her own self-contained Moses basket, complete with bedding.

We changed at Tientsin. Fortunately, we didn’t have to cross over to the Tsuipu Line, our train was shunted back to where we were.

We arrived at Tsinan 2 hrs. late and therefore missed the express connection. Reached Weihsien at 6.30 and were transported to our Camp in busses. The first night we slept in a common dormitory, we had straw mats and some fortunate people had mattress, the crowd who arrived a couple of days before we did, rallied around and brought us blankets and mattresses. Everyone envied Christine as she was carried around in her own self-contained Moses basket, complete with bedding.

This campus must have belonged originally to some college, as there are blocks and blocks of little rooms mostly single and a few of 2 connected. The type you know well. The following morning we had to go to the wash house for the necessities and it was bitter cold. After breakfast a roll call was made, after which we, the Talbots, were allocated a double quarter because we are 5 in number, thank goodness, quarters l and 2. The Wallises are our neighbours then, Dregges, Jones, Carters, Barns, Ladows and last of all the Marshes. I have not spoken to Marie and do not intend to. Daisy and George have come out trumps, they are behaving as all good neighbours do. I was pleasantly surprised. It is a long way off to the Ladies’ lav. from where we live. The Gents are situated in the next block, so Sid, has had to shed all sense of false modesty and take the gerry suitably veiled to empty it in the Gents as often as was necessary.

Version 2 of "March 27th 1943" was written by Ida Talbot after the War.

There are several versions as she wanted to publish them eventually.

This seems to be the first copy as the paper is same size as the diaries and beige and thin.

Dear Freda

(version 2)

I am afraid I have been compelled to allow a week to lapse before writing, as I have been extremely busy. Huge quantities of diverse furniture were heaped in piles at various points in the courtyards and alleys and I managed to pick up a table, a couple of chairs, rough stools and planks of wood which will later, I hope, be made into shelves.

Let me get back to the journey, from the starting point: it was long, monotonous and arduous after a very long and dreary wait at Chinwangtao Station. It was not long before we had exhausted our small talk and we not allowed the distraction of talking to the porters, booking clerks, etc., as they were not in evidence. In fact, no one paid any attention to us, which is quite unusual for the normally inquisitive Chinese peasantry and the Chinese travellers just behaved as though we were not there. We were joined at the Station by an American missionary, wife and son, they look very pathetic with their few belongings but how mistaken we were by their appearance. Suddenly we all packed up as there seemed to be a rippling movement, we knew

that the time for our departure was near, this ripple was caused by the arrival of some very officious-looking Chinese minor officials who ordered us to place our baggage in piles and then stand by them. When this was done, the leader shouted in a harsh voice whether there were any cameras, radios, etc. in our luggage. And yet he seemed to be relieved at our concerted “no”, and passed the luggage.

We had a terrific reception at the Mines. At Linsi Mr Walravens, Dufrasne and Kelsey brought a huge quantity of food, it was so unexpected that we were speechless and very touched. And parting was a very tearful one.

Then at Tongshan, Bill Gunn, Grace Hill Murray, Vera Dutoff and Ducuroir came with 28 boxes of foodstuff as well as cigarettes, tinned milk and biscuits. The Japanese Consular Official who accompanied us from Chinwangtao was a particularly sympathetic man, looking extremely spruce and smelt of perfumed soap. He tried to be helpful and Jock Allan knowing that I could speak a smattering of Japanese asked me to interpret. Very haltingly I asked the Consular Official if we could take this vast quantity of on board, he agreed providing he could examine the boxes. It was only perfunctory, of course, and everyone’s “face” satisfied. It was sadder this time for we were leaving Britons behind.

I am afraid I dozed whenever I could as Christine slept quite a lot. The two older children managed to occupy themselves playing with the others along the aisles. If they became too exuberant some parent soon told them off. We stopped at the various stations, more internees came aboard and as these people were not as fortunate as we, it was generally agreed to share our food with them, then at Changli almost a hundred Priests from the Dutch Lazarist Mission joined us. The sight of so many men heartened us for until then the women and children were in the majority.

We had to change trains in Tientsin and, of course, here one of our dreaded ordeals had to be lived through, the usual vast horde of porters were conspicuous by their absence in fact we were roped off from the general public and the Japanese sentries made sure that the public would not be contaminated by concourse with us. I believe Mr Joerg came to the station to see how things were going, I was too much tied up with the children to have even noticed him but providentially after we had painfully de-trained ourselves, for some unaccountable reason the authorities decided that after all they would shunt the train we had just left on to the Tsinput

line, so back to the train again we went.

We arrived at Tsinan 2 hours late and thereby missed the express connection. We managed to change trains in record time for on this occasion the authorities had recruited men to shift the baggage from one train to the other whilst we “helpless women” looked after the arriving pieces. When the train started moving, we had to pick up threads again, some of us to feed our babies, others to re-settle the old folks and still others to amuse the older children. But the train was very badly overcrowded, the priests and men stood packed like sardines in a tin. The train suddenly stopped in a very desolate valley we were surprised to see a squad of Japanese soldiers march out and proceed to do P.T. It was a blind, of course, as apparently the rails further along had been blown up and we had to wait for the completion of the repair work.

Arrived at Weihsien at 7.30 and again we lined up beside our luggage, Christine still sleeping peacefully in her Moses basket. Those Chinese who were allowed on to the platform could no resist coming and having a peep at the baby sleeping so confidently in the wicker basket. After a great deal of fuss and palaver, we were told to pile into busses, the one I went on kept breaking down but I wasn’t worried as it was full of hefty Priests. It was quite dark when we arrived at the Assembly Camp after standing around, it seemed for an age, being counted and recounted we were told to go to a largish building for the night, the priests were allocated the ground floor and we upstairs: you never saw such a sight in your life. Men, women and

children: some looking tired, others happy, babies crying. The Tsingtao which came in the day before prepared a sort of supper for us, I don’t know how they managed it. Sister Eustella made her first appearance and she certainly made a grand debut – that of a lady of mercy. She borrowed blankets, mattresses, etc. for those who needed them. As soon as we were allowed to

we scrambled for those Japanese tatamis, we managed to get two, and slept till the wee hours. The medley of noises and smells, what a hell pot.

This campus must have belonged originally to some school or other as there are blocks of little single rooms and a few connecting rooms.

The following morning after a cold wash in an icy wash place and toilet, we had

breakfast of millet and bread.

Then presently there was a roll call, the riot act was read out to us and rooms allocated. We were given two connecting rooms in Alley 6: the playing field is immediately behind and the bakery to be immediately in front. The Wallisis, then Dregges, Joneses, Carters, Barnes and last of all the Marshes. As Sid has been allocated the first house, he was made warden of the row. The Ladies’ Latrine is a good distance away from where we live, whereas the gents next door to the bakery which is in front of us, so Sid, with false modesty laid aside has to empty gerries every morning. It's hard on him, but there you are.

Letters and comfort parcels are admissible: the mail is passed out once weekly – on Mondays.

The life is one continual work for me as I am having to feed and look after Christine all day. It is hard, but I have no time to be bored. As we take Christine with us to the dining room for our three meals and is placed at the bottom of the table close to the wall to be propped up, and being always dressed in her blue coat ( which I had made in Chinwangtao) she is known as the little baby in blue.

I have never seen such a congregation of religious folk – so many priests – and as for the nuns, the prettiest seem to wear the veil.

The American sisters are extremely jolly, the Dutch and Belgian quite subdued and mouse like. We all eat together in a common dining barn to which we have to bring our own utensils, line up for servings, help ourselves to bread and tea and seat ourselves any table for a feed. Many of us seem to have brought a lasting amount of butter, jam and milk – the religious folk are not excluded, so far, the food is excellent although it is always sloppy and much to my relief conducive to ample milk supply for Christine. Breakfast at 8.30, lunch at 12.30 and supper at 6.30.

I forgot to mention that Mrs Simmie, Louis Ladow and wife and Bill live in our alley. Louis has been very helpful.

The morning after we arrived, as I was coming down the stairs, I met the Consular Official who greeted me and asked me if I had a stove, when he heard that I hadn’t he said that he would see that I would get one. (Gratitude for the little interpreting I did for him I guess.) So I did get a stove but we had a lot of trouble lighting it because we didn’t have sufficient lengths of piping, the minimum is three but the contractor’s coolie only brought 2. However, we later greased his palm and got a third one. Now I have to cope with Christine’s food, I have to make cream of heat porridge, etc. and we also have frequent visitors who come for a warm, as only families with children under one are receiving stoves.

In our 2-room shack, we put Marie and Wendy when they arrived two days’ later, then when they went to live in their one room, we put the Hennings who came from Peking and actually it was Bill Chilton who asked Sid to do this. They were friends of my father’s and quite elderly so we felt it was the only decent thing we could do. We were a little squashed because the Talbots, all 5, had to sleep in the backroom and the 2 Hennings had the front room. One camp bed was lifted up during the day. W.B. Chilton will climb to be top dog I think, because he has

the personality and organising ability, as you know. I haven’t seen much of him yet.

Our lodgers left today so we will now be able to straighten things out.

The K.U.K. have done a good job, not a thing lost. I wish I knew that I could have brought more useful household articles, such as pails, curtains, fancy plates, tea pots, etc. I do miss them.

I will work on my promise soon and it will be a humdinger. The people here are full of fun and I am getting more laughs in one day than I would have in one year in Chinwangtao.

Please remember me to Will, Olaf, August and yourselves. I will write next week. Thank you very much for your friendship. I appreciate it much. Without you I should

have been extremely lonely and you helped to make my days pleasant ad companionable.

Love to you all,

Ida

It looks as if she wrote this while still working for BB Vos as it is on their typical green paper.

Dear Freda,

I am afraid I have been compelled to allow a week to lapse before writing, as I have been extremely busy to settle in. Scrounging furniture from the piles placed are various points in the courtyards and alleys, I managed to pick up a table, a couple of chairs, rough stools and planks of wood which will I hope later be used for shelves.

Let me get back to the journey, from the starting point: it was long, monotonous and arduous after a very long and dreary wait at Chinwangtao Station. The formerly familiar faces of the porters, booking clerks, etc. were not in evidence and in fact no one paid any attention to us which is quite unusual for the normally inquisitive Chinese peasantry. We were joined at the Station by an American missionary, wife and son looking very pathetic with their few

belongings. When suddenly there was a ripple of movement, we knew that the time of our departure was near, this was borne out by the arrival of some very officious looking Chinese minor officials who ordered us to place our baggage in piles and when this was done, the leader barked out the query whether there were any cameras, radios, etc. in our luggage. He was relieved at our concerted “no” and passed the luggage.

We had a terrific reception at the Mines. At Linsi Mr Walravens, Dufrasne and Kelsey brought a huge quantity of food, it was so unexpected that we were speechless and very touched. And parting was a very tearful one. Then at Tongshan, Bill Gunn, Grace Hill Murray, Vera Dutoff and Ducuroir came with 28 boxes of foodstuff as well as cigarettes, tinned milk and biscuits. The Japanese Consular Official who accompanied us from Chinwangtao was a particularly sympathetic man, looking extremely spruce and smelt of perfumed soap. He tried to be helpful and Jock Allan knowing that I could speak a smattering of Japanese asked me to interpret. Very haltingly I asked the Consular Official if we could take this vast quantity of on board, he agreed providing he could examine the boxes. It was only perfunctory, of course, and everyone’s “face” satisfied, the “cargo”was put on board and once again farewells had to be made. It was even sadder this time for we were leaving Britons behind.

I am afraid I dozed very much for Christine slept quite a lot and was causing no trouble at all. The two older children managed to occupy themselves playing with the other children along the aisles. As we stopped at the various stations picking up more internees and as these people were not as fortunate as we, it was generally agreed to share our food with them, then at

Changli almost a hundred Priests from the Dutch Lazarist Mission joined us. The sight of so many men heartened us for until then the women and children were in the majority.

We had to change trains in Tientsin and, of course, here one of our dreaded ordeals had to be lived through, the usual vast horde of porters were conspicuous by their absence in fact we were roped off from the general public and the Japanese sentries made sure that the public would not be contaminated by concourse with us. I believe Mr Joerg came to the station to see how things were going, I was too much tied up with the children to have even noticed him but providentially and for some unaccountable reason the authorities decided that after all they would shunt the train we had left on to the Tsinput line, so back to the train again we went.

We arrived at Tsinan 2 hours late and thereby missed the express connection. We managed to change trains in record time for on this occasion the authorities had recruited men to shift the baggage from one train to the other whilst we “helpless women” looked after the arriving pieces. When the train started moving, we had to pick up threads again, some of us to feed our babies, others to re-settle the old folks and still others to amuse the older children. When suddenly the train stopped and to our surprise, we saw a squad of Japanese soldiers march out and proceed to do P.T. It was a blind, of course, as apparently the rails further along had been blown up and we had to wait for the completion of the repair work.

Arrived at Weihsien at 7.30 and again we lined up beside our luggage, Christine still sleeping peacefully in her Moses basket. Those Chinese who were allowed on to the platform could not resist coming and having a peep at the baby sleeping so confidently in the wicker basket. After a great deal of fuss and palaver, we were told to pile into busses, the one I went on kept breaking down but I wasn’t worried as it was full of hefty Priests.

It was quite dark when we arrived at the Assembly Camp after standing around, it seemed for an age, being counted and recounted we were told to go to a largish building for the night, the priests were allocated ...

(here ends this manuscript)

N.D.L.R.

by Leopold Pander Jr.

In those days, and with the facilities given by the bank, our dad had a steady correspondence with his family in Belgium.

We found this letter in our family archives.

Here is a large excerpt:

lundi, 21 avril 1941

Chers tous,

Pour la première fois depuis longtemps, je ne vous ai pas écrit le dimanche, hier ! Je suis parti vendredi pour Tongshau, le patelin où habitait Deugis, pour faire visite aux Belges résidant là-bas et surtout pour vous expédier des Liebesgaben qu'il est impossible d'envoyer d'ici. Vous recevrez - si vous n'avez déjà pas reçu - de la viande, du lard, du jambon et du saindoux (12 colis pour la maison, 12 pour Martin) expédiés par un Mr. Heyman. C'est un bon camarade, très dévoué, qui sera très touché par la petite carte de remerciements que vous ne manquerez pas de lui adresser.

Je suis rentré hier soir, fourbu par le voyage, fatigué par les nombreuses réceptions en mon honneur et dégoûté une fois de plus du climat du Nord de la Chine. Les vents jaunes et de poussières sont encore assez supportables lorsqu'on est bien installé chez soi, portes et fenêtres fermées, mais en voyage, en train, sur les routes, ils deviennent horripilants. Je ne sais pas si vous vous rendez bien compte de ce que c'est qu'un «vent jaune» et peut-être ne me croyez-vous pas lorsque je vous raconte que depuis trois semaines nous croquons du sable, nous en mangeons, nous en respirons, nos oreilles en sont tapissées, nos yeux piquent, notre nez chatouille, notre peau craque de sécheresse, notre linge est sale, tout ce que l'on touche est couvert de poussières, on est énervé et on ne songe, on ne rêve, on ne parle que de pluie et on souhaiterait pouvoir se vautrer dans la boue ! Hélas ! Les augures chinois, après avoir annoncé que l'on n'avait plus vu depuis trente ans une telle intensité de vents jaunes, prédisent que pendant quarante jours encore les sables de Mongolie viendront se déposer dans nos parages et que nous pourrions espérer, avec la bonne volonté de Bouddha, avoir quelques pluies de printemps au mois de juillet. Quand Clava et moi parlons de Bruxelles, nous souhaitons nous trouver dans la forêt de Soignes sous une pluie battante ! Ah ! Rien qu'un peu de cette bonne odeur de la drache, de ce délicieux parfum que dégage la bonne terre humide de chez nous...

»

[the rest of the writing is all family gossip]

Translated by Google

Translated by Google