- by John Hoyte

[Excerpt] ...

[...]

August 1945 had come, and there were

rumors of Allied victories at sea. The Japanese published a weekly newspaper in English that was full of propaganda. Reported Japanese victories were closer and closer to Japan, so we sensed that the war was coming to an end.

August 1945 had come, and there were

rumors of Allied victories at sea. The Japanese published a weekly newspaper in English that was full of propaganda. Reported Japanese victories were closer and closer to Japan, so we sensed that the war was coming to an end.

The two prisoners who had escaped earlier, Arthur Hummel and Christopher Tipton, were with the Nationalist forces out in no-man’s-land, and they managed to get news into camp by means of the coolies who emptied the septic tanks each week. The coolies tended to have terrible teeth, with lots of cavities into which a message on a tiny scrap of paper could be stuffed. They also tended to spit, dislodging the message so it found its way unobserved to the ground, where a prisoner in the know could get the message.

This was all kept very secret so that the rest of us were out of the loop.

August 17, 1945, was clear, cloudless, and warm. We were in class that morning when the distant drone of an airplane caught our attention.

As it grew louder, we perked up our ears, for very few planes ever flew over the camp, and those that did were at high altitude. Quite suddenly, the sound was so loud that we rushed to the windows and looked out.

There, unbelievably, was an American bomber, a B-24, flying low over the trees, so low that we thought it might almost touch them. It climbed, circled, and came in low again.

The bold American star on its flank was unmistakable; it was clearly one of ours.

Everyone was outside waving wildly but also wondering if the Japanese would try to shoot it down. After all, as far as we knew, the war was still on. But the plane came down toward us so brazenly, so exquisitely, with such unimaginable reality.

The meaning was profound: This plane was for us! It was to give us a personal message.

Our little camp, out in the boonies, had been remembered. Could it be that the war was over?

The magical plane gained altitude, heading away, after passing over us three times. There was a gasp, a hint of disappointment. Someone said, “They are leaving us! One day they will come back and deliver us,” and so it seemed when an even-greater marvel took place, almost in slow motion.

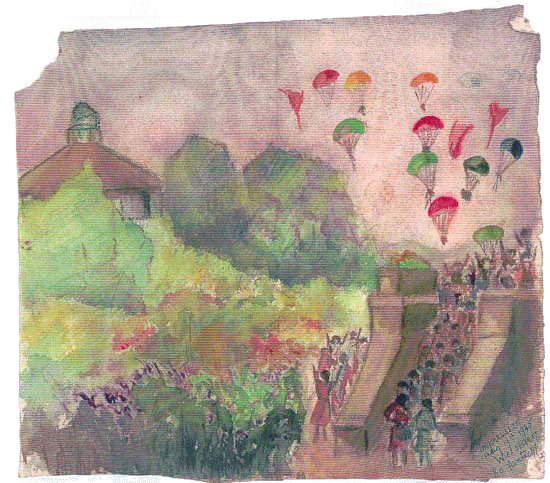

The plane’s undercarriage opened and seven dots appeared. Now it became clear that they were seven men parachuting down toward us.

And what parachutes! Their color was drab, but to us, they were in brilliant colors, the glorious colors of freedom.

How they contrasted with the shabbiness of the camp, for indeed we were drab. After all those months in captivity, most color had gone from our lives, with our clothes in tatters, devoid of color, and our food almost as colorless as it was tasteless.

So I can understand why the parachutes—so important to me—appeared to my mind as in brilliant colors. The more significant reality was that seven very real men were dangling from them.

The parachutes floated down to earth at such a leisurely pace, indeed like a vision from on high, almost too wonderful to take in and all in slow motion.

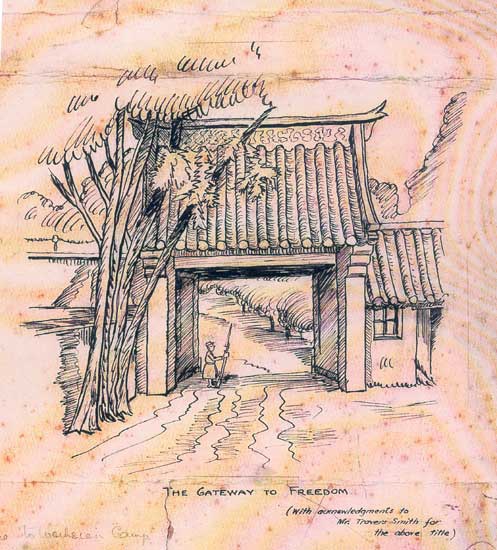

Without hesitation and disregarding the danger involved, we rushed toward the main gate of the camp, burst it open, and ran out into the fields. As we passed through it, a couple of guards brought their automatic rifles into firing position, but, in obvious confusion, they slowly lowered them.

Our goal was to reach the seven airmen. We prisoners were barefoot, and the ground was rough with broken glass, sometimes jagged metal, and prickly kaoliang vegetation, but we did not care.

Half a mile out in a field high with kaoliang corn, our seven godlike heroes were unbuckling their parachutes. They had their rifles at the ready, preparing to fight their way into the camp if necessary, but were now taken by total surprise by this horde of ragtag, barefoot prisoners surrounding them in jubilation.

I was one of the first to reach Jimmy Moore, an alumnus from Chefoo, who had volunteered for the mission to help free his old school. His uniform was impeccable, his ruddy complexion like a god’s, and just to touch his smart uniform was breathtaking. This was as close to worshipping a human being as a boy could get. Some of the adults and bigger boys carried him into camp on their shoulders, with us smaller ones tagging along.

The seven dismounted from their human chariots just inside the main gate, and their commander, Major Staiger, asked to see the Japanese commandant. A prisoner pointed to the hall where the Japanese officers had assembled.

Staiger, who was only twenty-seven, drew his two revolvers and strode in to face the commandant, seated at his desk with his hands spread out in front of him.

The moment was crucial for both sides, as the commandant probably could not be sure that Japan had actually surrendered. If it had, he knew, killing the seven would make it tougher for him and his men. If their country hadn’t, for him to surrender would be an extreme act of military cowardice and might lead to hara-kiri.

In the crucial moment, the commandant drew his samurai sword and revolver and handed them to the major.

In a brilliant response, Staiger handed them back and insisted, with one of the parachutists who spoke Japanese interpreting that they would work together in arranging relief for the camp.

We who were waiting outside were relieved to see the major come out with his revolvers in their holsters and a smile on his face. It is hard to describe the sensation of freedom that came over me.

Theo and I walked out through the guard-less gate with a sense of ecstasy. I asked him, Do you mean that we can go wherever we like?

After nearly four years in captivity, it was incredible that we now had freedom. After we had first come into camp, the world beyond the walls began to shrink and become unreal. It was almost a two-dimensional stage set. Our only reality was the narrow, colorless existence of confinement.

Suddenly, the outside world became not only three-dimensional but had also taken on the fourth dimension of apparently infinite possibility. From grayness, we now looked on a multicolored world. Indeed, the world was our oyster.

We were free.

For the next two weeks, the camp was run by the “fabulous seven”.

They were intelligent, reasonable, and gracious, and put up with our adulation with quiet ease.

[further reading] ...http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/JohnHoyte/JHoyte(web).pdf

#