- by Emmanuel Hanquet

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

It is 10 o’clock in the morning. To pass away the time a few people are walking about on the assembly ground which we generously call the sports field. It is the only place in the camp where it is possible to play baseball without running the risk of breaking a window or hurting a passer-by. It is also the place chosen by our gaolers to assemble the internees to reassure themselves that no prisoner has escaped.

It is 10 o’clock in the morning. To pass away the time a few people are walking about on the assembly ground which we generously call the sports field. It is the only place in the camp where it is possible to play baseball without running the risk of breaking a window or hurting a passer-by. It is also the place chosen by our gaolers to assemble the internees to reassure themselves that no prisoner has escaped.

The weather is marvellously sunny and the temperature is tolerable. And what was I doing on the sports field where there was no shade at this time of day?

I seem to remember that I had noticed the sound of a plane engine, strange and unusual because it sounded different from the engines of the Japanese planes that we were used to hear.

Curiosity had drawn me to the sports field, which was more open and was on one boundary of the camp. Some in the group on the field with their heads in the air have spotted a red, white and blue roundel painted on the side of the fuselage of the plane which is now flying over us.

Speculation were rife: ‘Might it be a French plane?’ ‘What’s it doing in these parts?’

Later we were to learn that American planes have the same colours as the French ones. ‘Has it lost its way?’ ‘Is it doing a reconnaissance?’ I should explain that from the air our camp looks like a Chinese village but the Allies were to recognise us because of the coloured shirts that a number of us were wearing.

Once the camp has apparently been recognised the plane begins to circle then, above some nearby fields not far from the perimeter wall it releases ten or so parcels dangling from red, yellow and green parachutes. What a lovely sight! A few minutes later a second drop releases a further dozen bundles.

On the third run, we see things that look like sacks of potatoes appear, then these suddenly acquire arms and legs and above them we see big white parachutes opening. There are seven of them.

What should we do?

Despite the expressionless faces of our gaolers, a rumour had been going round the camp that the Japs had been having some setbacks. We knew nothing of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki which had brought Japan to sign a document of unconditional surrender on the15th of August 1945.

I had tried to find out more from some Chinese who had delivered a cartload of vegetables to us. Taking advantage of one opportune moment, I had gleaned in confidence that the Japanese were abandoning the nearby town.

I had spread this long hoped-for news throughout the camp.But only on that marvellous morning of the 17th of August did this great hope seem to become a reality…

Now, while one of our comrades, strong and bold, had hitched himself up onto the boundary wall to see just where the parachutes had fallen, the rest of us had, as one, rushed towards the gate to the outside which was guarded by two sentries.

There were twenty or thirty of us hurtling down the slope towards it.

Were those Japanese who were on duty going to react?

After a few seconds of uncertainty, we were out in the countryside running towards those that we supposed, and hoped, were our liberators.

In the midst of tall heads of maize, standing on the tomb of a Chinese notable, an American major was giving orders. He seemed to us to be the liberating angel in person. What a welcome.

We looked around for his companions. ‘There are seven of us,’ he said, ‘and we have twenty bundles to gather up as well as the parachutes.

To work, now!’ It took barely an hour to assemble the team and the materiel. One member of the commando, a 17 year-old Chinese, a volunteer interpreter, making his first jump, had broken his foot on landing.

We returned to the camp in triumph bearing them all on our shoulders. We were wild with joy.

However, the major calmed us down and advised us to let him go ahead with his men, each armed with a Bren gun and with revolvers in their belts.

They could reasonably fear a violent reaction from our guards. Nothing of the sort, happily.

The Japanese commandant had assembled all the guards and was impassively waiting for the parachutists to arrive. He knew full well that the war was over…

Two interpreters, British Eurasians who had been interned with us, were present. The exchange between the Americans and Japanese passed off smoothly.

Orders from on high confined our former gaolers to their accommodation while entrusting to them the guarding of the camp at nighttime.

We learned that a guerilla force of communists were heading for the camp hoping to take us hostage.

Despite our hungry curiosity to know everything, our rescuers were too busy, that day, to tell us about the operation that had been devised to rescue us.

But the following day we got to know the details: they were all volunteers for the mission, and had been brought together just twenty-four hours beforehand in order to get acquainted with one another and to clarify individual tasks. When told of the risks they were likely to run, none of them had backed out. The team consisted of a major in his thirties, the leader of the mission; a captain; two other officers - one for liaison and one a radio specialist; an orderly; a Nisei [an American of Japanese origin]; and a young Chinese who would act as interpreter if needed.

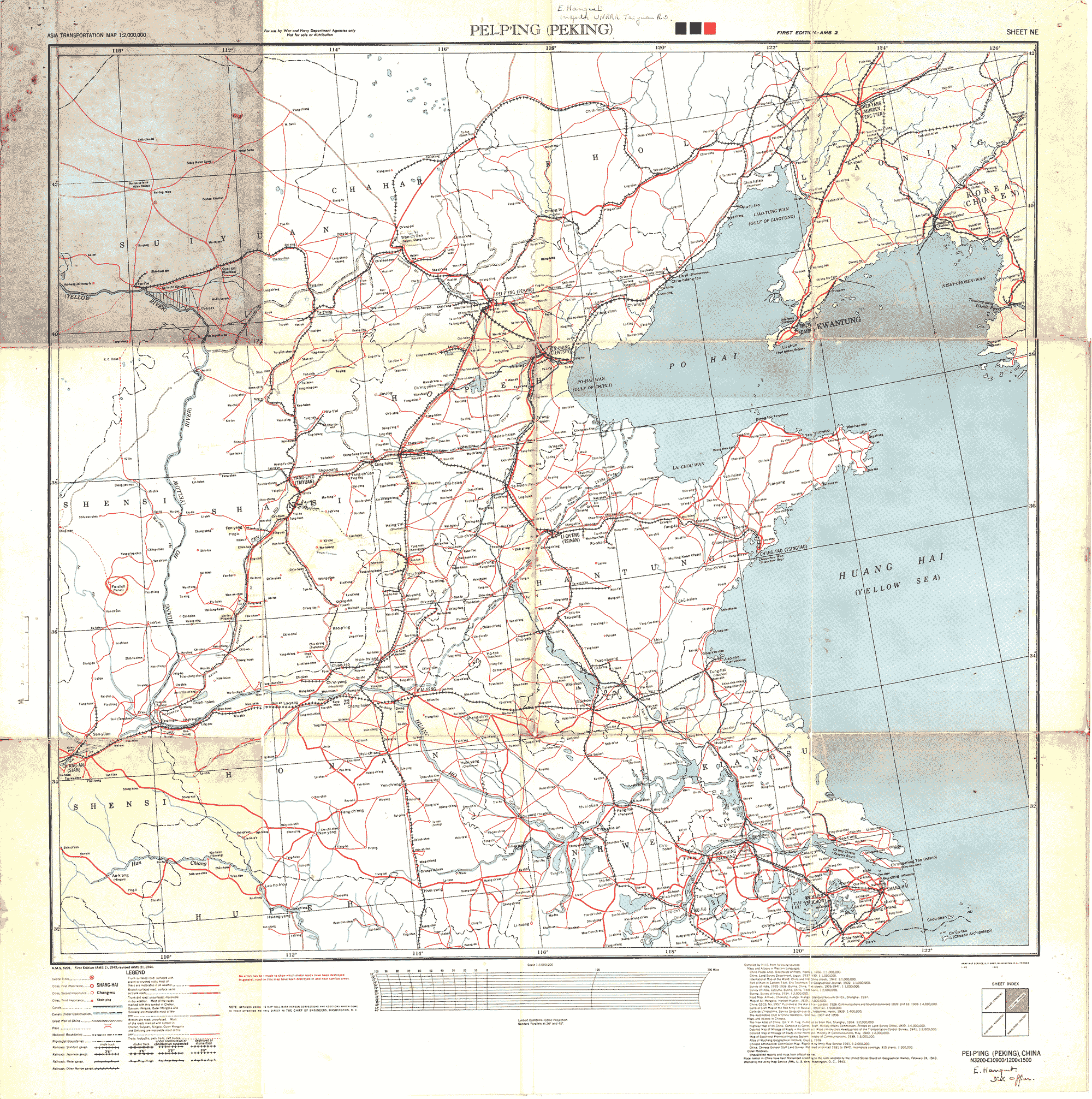

They had come from Kunming, an American base in Yunnan Province in South China, and had flown for six hours to reach Shantung Province and begin the search for our camp. After dropping them the plane had continued northwards to a base which had recently been liberated and which was not so far to fly. In the following days, other packs arrived from the sky containing clothes, food and shoes.

[excerpt]

As already told by many of you, and in spite of the armed guards standing at the entrance of the camp, we forced the gate and rushed into the fields out of the camp in order to cheer and congratulate our rescuers.

Major Staiger was in charge of the team.

He had already put his harness and parachute aside and was standing on top of a mound when we first saw him.

This mound was a tomb. For centuries, the Chinese used to bury their ancestors in the fields and they built a mound to mark the place of the burial.

The highest mound was assigned to the oldest ancestor.

Major Staiger accepted our cheers but very soon, wisely said: “Please gather next to this tomb, all the parachutes with their loads and also, bring here the men who had jumped with their white silk parachutes.

About more or less an hour later, everything was ready and we hoisted the seven men on our shoulders as, of course, we wanted to honour them as our heroes.

When we approached the walls of the camp, Staiger gave us the order to let them down so that they could encounter the captain of the camp and the guards who were watching us coming.

This was a wise measure , since the guards were all armed and our rescuers did not know at that moment what the Japanese’s reaction would be in regard to this particular situation.

As I re-entered the camp on my own, I met two friends who were standing alongside the wall ready to defend us in case of a violent Japanese reaction. They were Roy Chu and Wade.

Both had an axe in their hands, and they had put their red armbands to be recognised. Only then, did I discover that a group of bachelors in the camp had organised a secret brigade to protect us from the Japanese, in case they would start their plan to exterminate us all.

Fortunately, this did not happen.

Everything went smoothly when the rescue team met the guards. Both groups received instructions not to fight and we would sleep in peace during the next two more months that we had to stay in camp, allowing intelligence officers to screen the former history of every one of us and to finally be able to evacuate my group to Peking by a plane, a C-46, on October 17, 1945.

[further reading] ...http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/hanquet/book/Memoires-TotaleUK-web.pdf

#