- by Lagdon Gilkey

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

We deposited our gear on the cold cement floor, and found mats, for our beds. Then some of us went out to look for the toilet and washroom. We were told they were about a hundred and fifty yards away: “Go down the left-hand street of the camp, and turn left at the water pump.” So we set off, curiously peering on every side to see our new world.

We deposited our gear on the cold cement floor, and found mats, for our beds. Then some of us went out to look for the toilet and washroom. We were told they were about a hundred and fifty yards away: “Go down the left-hand street of the camp, and turn left at the water pump.” So we set off, curiously peering on every side to see our new world.

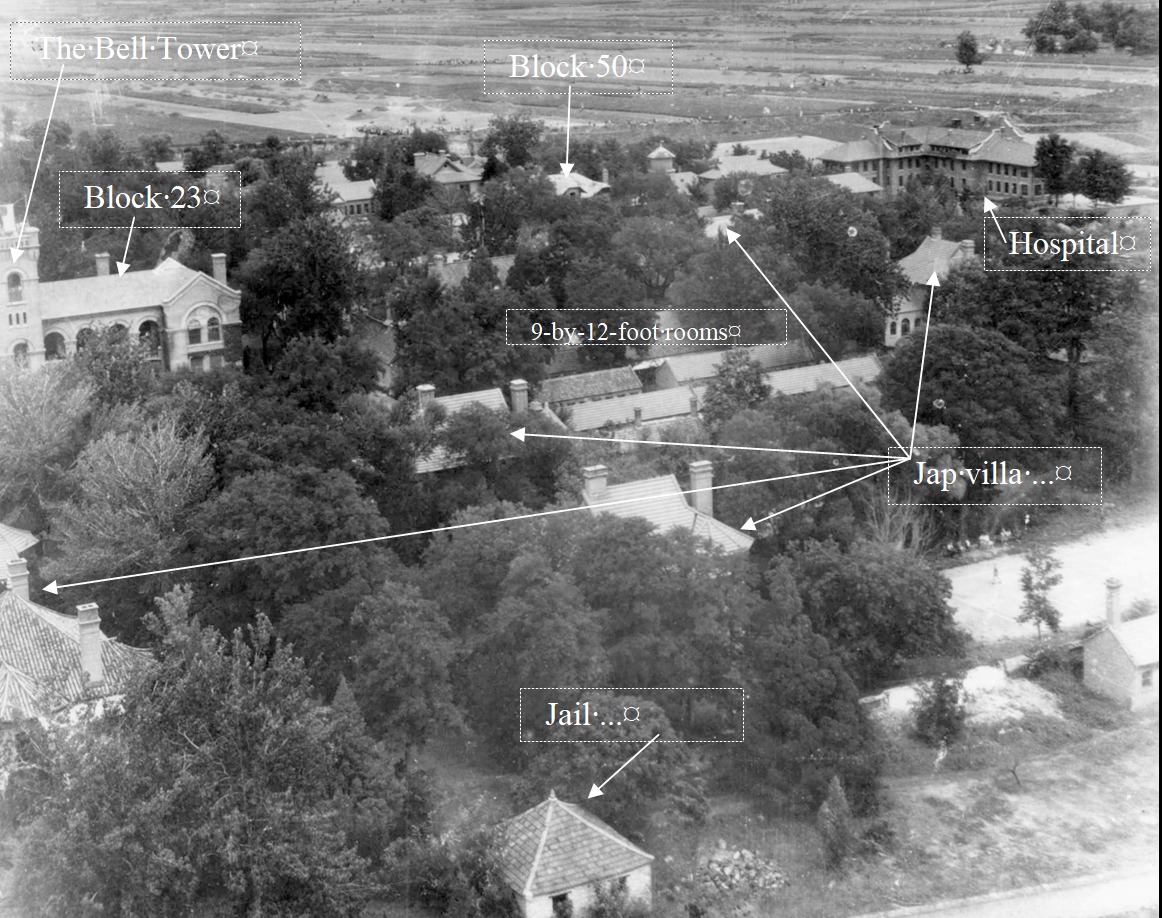

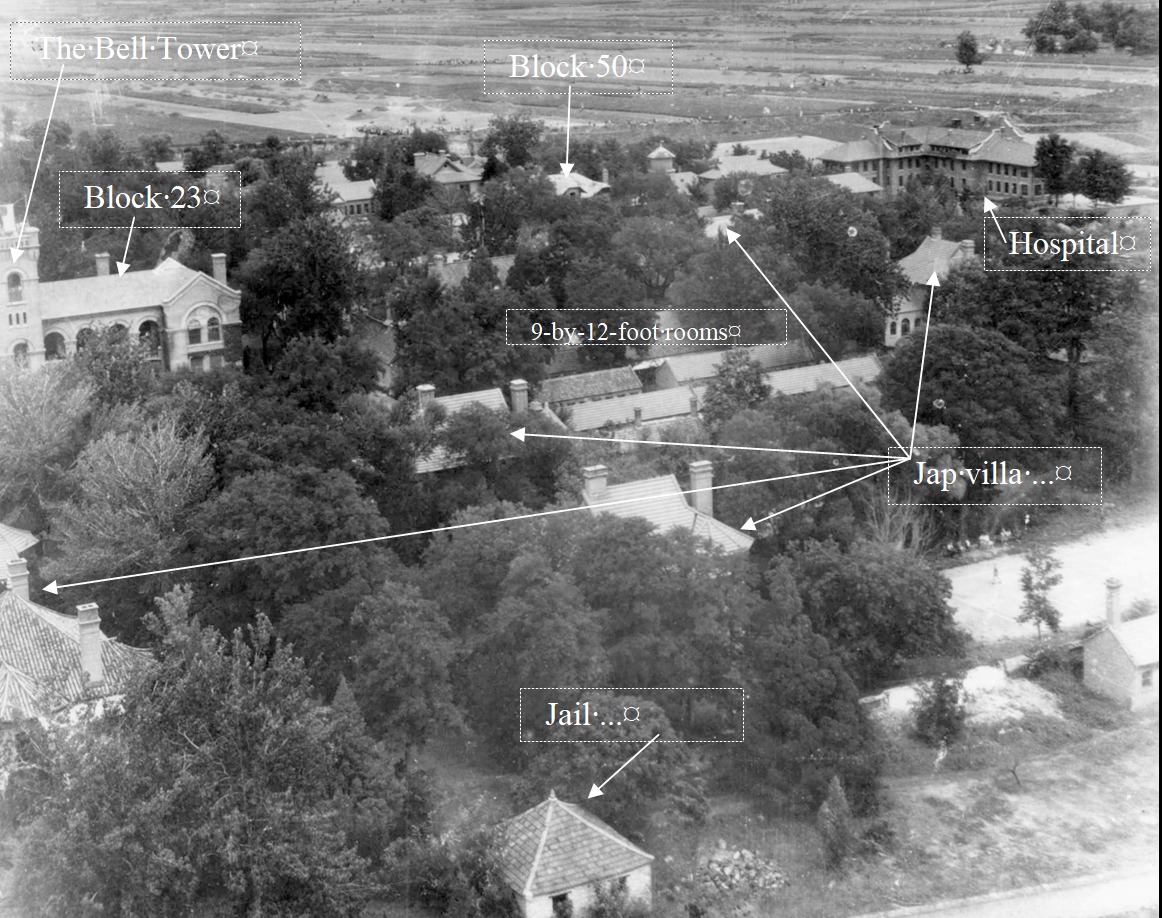

After an open space in front of our building, we came to the many rows of small rooms that covered the camp except where the ballfield, the church, the hospital, and the school buildings were.

Walking past these rows, we could see each family trying to get settled in its little room in somewhat the same disordered and cheerless way that we had done in ours. In contrast to the unhappy mutterings of miscellaneous bachelors, these rooms echoed to the distressed cries of babies and small children.

Then we came to a large hand pump under a small water tower. There we saw a husky, grinning British engineer, stripped to the waist even though the dusk was cold, furiously pumping water into the tower. As I watched him making his long, steady strokes, I suddenly realized what his presence at that pump meant.

We ourselves would have to do all the work in this camp; our muscles and hands would have to lift water from wells, carry supplies in from the gates. We would have to cook the food and stoke the fires —

... [further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/BOOK/Gilkey-BOOK(WEB).pdf

[excerpt]

Back outside, we strolled around for our first real look at the compound. I was again struck by how small it was—about one hundred and fifty by two hundred yards.

Even more striking was its wrecked condition.

Before the war, it had housed a well-equipped American Presbyterian mission station, complete with a middle, or high, school of four or five large buildings, a hospital, a church, three kitchens, bakery ovens, and seemingly endless small rooms for resident students.

We were told that, years before, Henry Luce had been born there.

Although the buildings themselves had not been damaged, everything in them was a shambles, having been wrecked by heaven knows how many garrisons of Japanese and Chinese soldiers. The contents of the various buildings were strewn up and down the compound, cluttering every street and open space; metal of all sorts, radiators, old beds, bits of pipe and whatnot, and among them broken desks, benches, and chairs that had been in the classrooms and offices.

Since our “dorm” was the basement of what had been the science building, on the way home we sifted through the remains of a chemistry lab.

Two days later we carried our loot to the hospital to help them to get in operation.

[excerpt]

With so many people living in such unsanitary conditions and eating dubious food at best, we expected a disaster in public health any day.

The greatest need was for a working hospital.

The doctors and the nurses among us grasped this at once, and so began the tremendous job of organizing a hospital more or less from scratch.

Perhaps because the mission hospital building had contained the most valuable equipment, it was in a worse state than any of the others. The boilers, beds, and pipes had been ripped from their places and thrown about everywhere. The operating table and the dental chair were finally found at the bottom of a heap at the side of the building. None of the other machinery or surgical equipment was left intact.

Under these conditions, considering that there was as yet no organization of labor in the camp, it is astounding that these medics and their volunteers were able to do what they did.

Inside of eight days they had the hospital cleaned up and functioning so as to feed and care for patients. In two more days they had achieved a working laboratory. At the end of ten days they were operating with success, and even delivering babies. This was, however, not quite quick enough to save a life.

Four days after the last group arrived, a member of the jazz band from Tientsin had an acute attack of appendicitis. Since the hospital was not yet ready for an operation, he was sent to Tsingtao six hours away by train, but unfortunately he died on the way.

[excerpt]

We were, in the words of the Britisher, “a ruddy mixed bag.” We were almost equally divided in numbers between men and women. We had roughly four hundred who were over sixty years of age, and another four hundred under fifteen. Our oldest citizen, so I discovered, was in his middle nineties; our youngest was the latest baby born in the camp hospital.

[excerpt]

Almost as soon as our committee was formed, a house-to-house count began. Gradually we filled in with names and numbers the great map of the compound that hung in the office. All went well until we came to the hospital.

There on the upper floors lived about 250 Dutch and Belgian monks. To our dismay, we discovered that apparently not even the Catholic leaders had any idea how many monks lived there or who they were. They were so jammed into each dorm that no man in a given room knew how many it held. Thus we almost had to buttonhole them one by one in order to make our list.

[excerpt]

After being badly burnt, the doctors in the hospital did a wonderful job.

A British doctor for the Kailan Mining Company put picric acid on the bandages and did not take them off for about ten days.

Due to the sulphanilamide that was smuggled into camp through the guerrillas, I was able to avoid infection. When the bandages finally came off, new skin had grown almost everywhere.

Within three weeks, I was hobbling around. In six months all that was left to show of the burn was a rather grim abstract color effect of yellow and magenta.

I learned through my experience that ours was a remarkable hospital.

Devoid of running water or central heating, it managed to be not only efficient but personal. It seemed to me a far better place in which to be sick than many “modern” hospitals, equipped with the latest gadgets but run on impersonal terms. It is this negation of the individual person, this sense of being “the bladder case in Room 304,” or “that terminal heart case down the hall”—not its food or even its service—that makes many an American hospital, despite its vast efficiency, a dreaded place in which to be sick.

The nurses and doctors, who formed the backbone of the staff of our hospital, had, of course, to work for long hours since no one could replace them at their tasks. But as I soon came to realize, a lot more than their skill was needed.

Among the essential services provided were a pharmacy where medicines (bought with a camp fund derived from a tax on comfort money) were given out and a lab where urinalyses, blood and other tests could be performed.

There was also a diet kitchen with its own staff of cooks and vegetable preparers (all women), a butcher, a supplies gang, a stoker, and a wood chopper. The hospital also had a hand laundry; there five women and one man washed the many sheets, towels, and bandages that were needed for the thirty or so in-patients.

To keep the building itself clean, a crew of moppers, dusters, and window cleaners daily made the rounds of the rooms and wards.

And finally, there was a staff of men orderlies and girl servers who helped the nurses to wash the patients and make them comfortable.

What made this small hospital unique in my experience was the unusual relationship between staff and patients, and among the patients themselves.

The workers, who came every day to the wards, sweeping under a patient’s bed or bringing him tea, were not strangers moving impersonally in and out of his area. Rather, they were friends or, at least, acquaintances who entered the patient’s life and communicated with him there.

They had known him as a person in camp before he became a case in the hospital, and thus, greeted by them as a person, the patient never felt himself to be merely a rundown organism whose end might well be the disposal in the basement. And, of course, the patients in the ward knew each other, too.

For example, when old Watkins in the bed at the far end reached the “crisis” of his serious case of pneumonia, we were all aware of it, and waited in concern for him to ride it out. When the ex-marine bartender, the foreman of a “go-down” in Tientsin, and the Anglican priest—all of whom were the orderlies in the ward I was in—made up our beds and carried out our slops, they would find time to ask me about my feet, kidding me for thinking I could walk on water.

Thus, quite unconsciously, because this was so normal among friends, they created a sense of personal community that for the sick is one of the few real guards against inner emptiness and despair. I left the hospital refreshed and sorry to return to normal internment life.

One of the hospital’s greatest trials was keeping up its stock of medicine. We had each brought into camp quantities of medicines in our trunks, as our doctors had directed, but this supply ran out before the end of 1943. The Japanese supplied only a fraction of the medicines we needed. The Swiss representative in Tsingtao, who came to camp once a month with the comfort money, was able to buy for us in local pharmacies only the most commonplace drugs.

What in the end saved our health was the happy collaboration between American logistics and the Swiss consul’s ingenuity.

The solution of this problem, when finally found, was so unusual we came to regard it as one of the best stories in the camp.

The two men who escaped from camp in June, 1944, were able to report via radio to Chungking that we were in desperate need of medicines. In answer, the American Air Force “dropped” a quantity of the latest sulfa drugs to the nationalist guerrillas in our immediate neighborhood.

But how were these supplies, obviously of Allied origin, to be smuggled into the camp past the Japanese guards?

The only man from the outside world permitted access was the Swiss consul in Tsingtao.

During a war, while other nations draft civilians into their armies, Switzerland, the perennial neutral, drafts civilians into its diplomatic corps—and with equally strange results. I remember, for example, dear old Duval, whom we had known as the nearsighted, brilliant, charming, ever courteous, but utterly unorganized, professor of history at Yenching University. Duval was a man with great popping eyes, a large, bald dome of a head, and an enormous black mustache. To our surprise and mild dismay we found that he had been made the assistant Swiss consul in Peking charged with extracting concessions for us from the Japanese military police! No man at the university was more respected and loved.

But it was hardly for his practical competence, his wily ingenuity, or his crushing dominance of will that we held him in such high esteem.

An even more unlikely selection—if possible—was Laubscher of Tsingtao, the temporary Swiss consul for Shantung Province. Laubscher [= Mr Egger] was, therefore, the man slated by the vagaries of fate to visit us regularly at Weihsien camp and to represent us and our governments to the Japanese. According to those who knew him in Tsingtao, he had formerly been a small importer.

He seemed formal, stiff, and somewhat reticent in his old-world ways, and certainly he was red-nosed and rheumy of eye—probably, so the report ran, from years of silent sipping while he sat on the club porch or while playing a quiet game of bridge in the men’s bar.

To look at Laubscher was to know that he would be quite incapable of pounding a table, even if he dared to, without hurting his hand. He seemed far too vacant of eye and unreal of being, too much inclined to try hard for a time but to effect nothing in the end. To be sure, we did not expect him to free us with a wave of his umbrella or even to force anything out of the Japanese against their wishes.

We were, however, aware that a firm will, steady and unrelenting pressure, and an ability to appear loudly outraged and genuinely angry while keeping a cool head could work wonders.

No one gave Laubscher the slightest chance of producing these traits out of his seemingly flabby ego. We waited, without much hope, to see what he could do for us.

What he did in fact accomplish, he explained to a group of us shortly before the end of the war. “You see, friends,” said he in his soft, old-world voice,

— “it all started when a Chinese dressed like a coolie rang the Swiss consulate bell in Tsingtao late one night and asked for me.

Since he would allow no one else in the room when he spoke to me—he said he did not trust my servants!—I was a trifle nervous. However, I tried—ahem!—to keep a walking stick near me!”

A small chuckle went round his group of listeners at the picture of the 120-pound (72.5 kg)Laubscher defending himself in single combat! “He told me,” Laubscher continued, “he had sneaked into town that night from the guerrilla band in the hills.

The day before the American Air Force from West China had made one of its usual ‘drops’ to the guerrillas.

Among the packages were four large crates.

It said in an attached letter—fortunately, friends, the Yanks had enough sense not to mark the crates!— these were designated for the camp at Weihsien.

The letter also said the crates were full of medicines. The next night, said the coolie, four of their band would come to the consulate at two A.M. to give the crates to me. I was to receive them quite alone and to tell no one.

It was up to me to get those crates into the camp to the internees.

“With these abrupt words the coolie left me. I must admit, friends, I was dazed and worried by all this. Not only was it risky; it was baffling—how could I carry off the role of fearless and omnicompetent secret agent?

For the first, but not the last, time during this episode, I allowed myself a little drink to calm my nerves!

“Sure enough, the next night at two, the bell rang at the gate. Having cleared the residence of servants, I opened the gates myself. Without a word four coolies marched in, each with a large wooden crate on his shoulder. At my order they piled them in my private office—I had planned to stow them away myself afterward in the consulate strong room adjoining it.

Then they left.

“I stared at this treasure: four boxes of medicines! How wonderful for the camp, I said to myself—but then I stopped dead, paralyzed by my next thought. How the hell—pardon me!—was I going to get those crates into the camp?

The Japanese knew well that bicarb and aspirin were the principal medications I could buy in Tsingtao. Where would I have run across all of this? For three hours I sat there on one of the crates almost in despair, trying to think of an answer—and again friends, I cheered myself a very great deal with a nip now and then!

“I kept asking myself: `What will I say when I try to get approval for this list at the consular police office here in Tsingtao?’

Discouraged there, I would then ask, `What can I tell the Japanese at the camp one hundred miles away when I arrive with all of these crates?’

And friends, it came like a flash! Suddenly my brain focused on the distinction between these two authorities, one in Tsingtao and the other at Weihsien, and my plan began to form.

“The next morning I told my Swiss secretary—I could, I decided, trust her—to type me out a list of all the drugs I could buy in Tsingtao.

There were about twenty-five to thirty such items, I should think. Most important, I told her, she was to leave four spaces in her list between each item.

Puzzled, but obedient to my command—ahem!—she did this and gave me a list about four pages long.

“Then I rushed with this list to the office of the Japanese consular police for their approval— everything I bring into camp must, you know, be okayed first by them.

I must admit that the official looked at the open spaces on my list with some amazement; then he looked at me curiously, as if to ask, `What the hell is this little fool up to?’ I tried not to notice his look or to seem nervous, so I hummed a little tune to myself, tapped my umbrella impatiently on the floor, and gazed out the window. Hopefully, so I told myself, this official cannot figure out anything wrong or dangerous about all those spaces. How could he, I thought, even form a sensible question to me about it?

If I wanted to use up the consulate stationery in such a scandalously wasteful way, then that was my funeral! I almost chuckled at this thought, as I stared out the window. At last, with a skeptical sigh, the Japanese reached in his drawer, pulled out his little seal, and gave the list his official chop.

“Elated I sped back to the consulate. I told my secretary to use the same typewriter and now to fill in the vacant spaces on the list with the names of all the drugs in the crates.

I must say, gentlemen, she did look at me then with new eyes!

“The next day I caught the early morning train to Weihsien, and was at the camp gates with the crates by mid-afternoon. Again the Japanese officials were puzzled. Where had this little foreign fool gotten all these drugs? Had a shipment come from Japan that they didn’t know about?

Again they looked curiously first at my list and then at me—and again I hummed my little tune and gazed in the other direction.

Apparently they decided it must be all right since there was no doubt about the consular chop at the bottom of the list.

The official said, `Okay’; at last the gates swung open; and my cart filled with the crates rolled into camp and up to the hospital door.

I shall never forget the look on the faces of you doctors when I took you out to show you the crates and then gave you that list with their contents!

“Again, friends, I must tell you that I had myself quite a nightcap when I got home again to Tsingtao!”

When Laubscher had finished and stepped down, everyone looked at him with as much amazement and curiosity as had the Japanese officials he had so completely outwitted.

From then on he was greeted whenever he came to camp with a new affection and certainly a new respect. I often thought that he deserved at the least a small statue placed somewhere near the hospital, complete with battered homburg, rolled umbrella, stiff collar, and rheumy—but cagey—eye! ‘

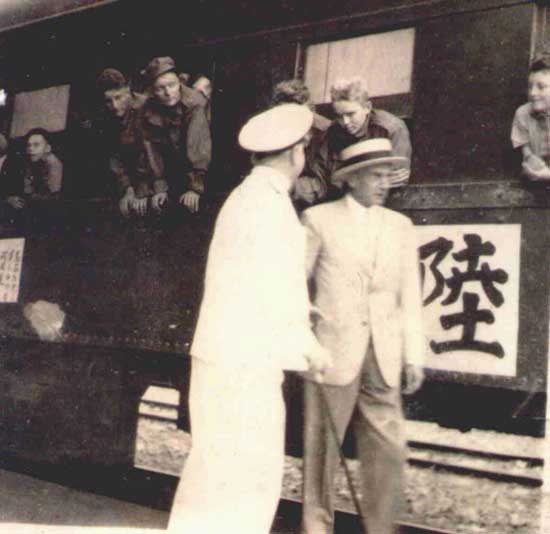

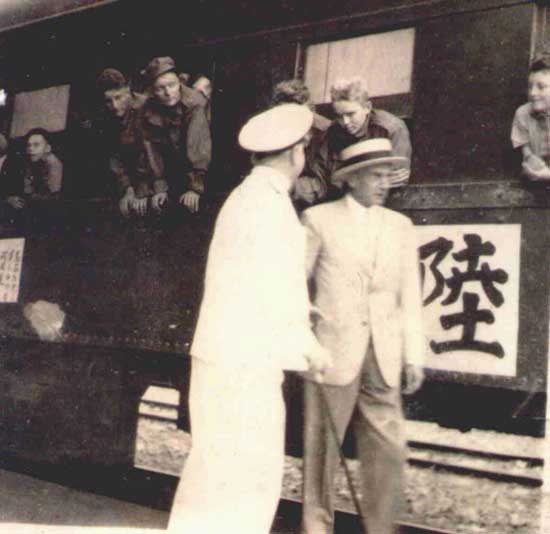

‘Qingdao Railway Station, Sept 25 1945 ---

‘Qingdao Railway Station, Sept 25 1945 ---

The Swiss Consul’

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/BOOK/Gilkey-BOOK(WEB).pdf

#

The Swiss Consul’