- by Norman Cliff

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

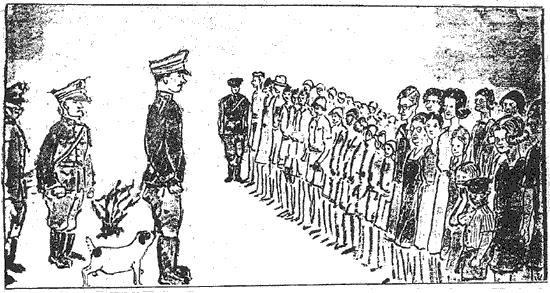

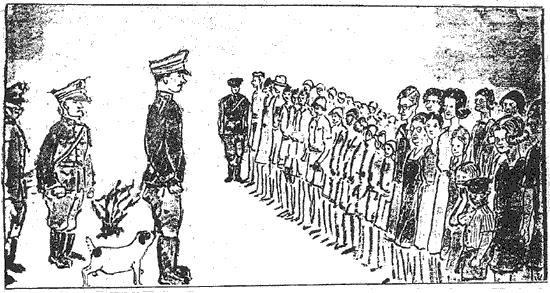

Every morning we had roll-call, numbering off in Japanese. The guard on duty would then salute the commandant and give a speech with which we soon became familiar. It went something like this ― :

Every morning we had roll-call, numbering off in Japanese. The guard on duty would then salute the commandant and give a speech with which we soon became familiar. It went something like this ― :

“This is Camp No. 3. Out of 98 inmates, there are 94 present. Three are on duty, and one is sick.”

As soon as this formality was over two of us boys would carry a crate of ashes out of the back gate next to the pump house. Emptying the contents, we would leave the crate lying upside down for a few moments while we took the coveted opportunity to look across the beautiful countryside and breathe the fresh air. It was a treasured moment of enjoying the open spaces, pretending to ourselves that we were not prisoners, before returning to the narrow confines of what came to be called Irwin House.

[excerpt]

In the spring of 1943 “Candleblower” (so named because of the face he made when listening to the guard’s speech at roll-call) handed over to Kosaka as commandant. This immaculately dressed man, with a kindly face, impeccable manners and a good command of English, stands out in my memory as unique and superior to any Japanese officials with whom we dealt up to that time and subsequently.

He never raised his voice in anger and always approached us with a courtesy which removed all the fear and tensions of those difficult days.

He would query after our health and well-being, and showed a special concern for the older missionaries.

[excerpt]

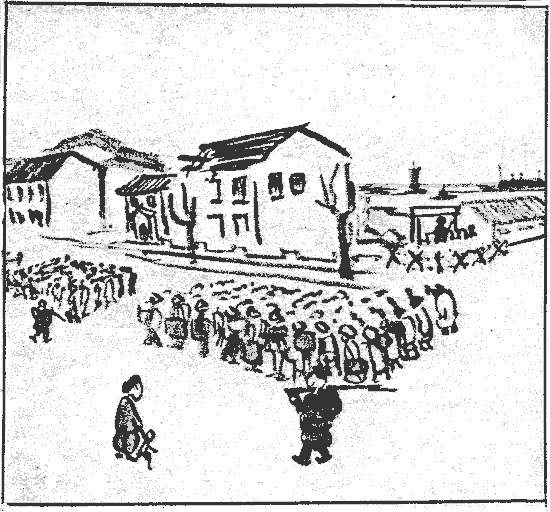

By this time the roll-call bell would ring. We would wait in four groups in different parts of the camp for the Japanese guards to inspect us, count us and make provision for those who were on special duties. While waiting for the guards we read books, studied languages, shared camp rumours and speculated about the future.

[excerpts]

Soon after I had become a roll-call warden, charged with the task of counting the personnel in Blocks 23 and 24, I was taking the guard along a line of internees outside Block 24 when Aunt Lilian (an American Presbyterian lady missionary who had known my parents at Shunteh) asked to see me after roll-call.

When I found her, she said with a tone of uncertainty in her voice, “Norman, I received some Golden Syrup from my mission station, but a rat fell into it as soon as I opened it. I’ve put it in the garbage box behind the building. If you’re interested, take it.”

[excerpt]

[excerpt]

While waiting for the guards to come round during daily roll-call, we would look longingly over the wall through the barbed-wire fences beyond the fields under cultivation to the distant villages on the horizon as far as the eye could see.

From camp rumours — bits of information which had come via cesspool coolies, and speculation — we gathered that the countryside around us was not uniformly under Japanese control.

While our camp was in the heart of Japanese occupied China, and to all appearances the Japanese ruled with undisputed control for hundreds of miles around us, there were in fact “pockets” quite close to us of Chinese puppet groups, officially assisting the Japanese but vacillating in their loyalties. Scattered in the area were evidently also pockets of Chinese Communist troops as well as Chiang Kai-shek units.

Fighting a common foe, the Japanese, there was an uneasy and uncertain truce between these heterogeneous groups.

[excerpts]

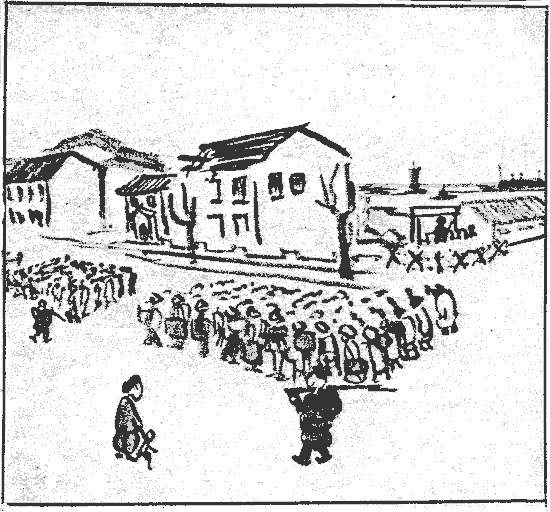

Roll-call that afternoon took three times the normal duration. Over the months it had become loosely organised and carelessly administered. As a roll-call warden, waiting outside the guardroom to ring a bell as a signal that the community could break up and return to work, I had noted that the figures chalked up on the blackboard in the guardroom had one day totalled 1,492 and the next day 1,518, and so on, with little effort to account for the discrepancies.

But from now on it was an exercise computed with the utmost care. The Japanese guards would count us over and over again. The roll-call period was prolonged. The Guards were gruff and their attitude one of distrust. If rows straggled crookedly, they shouted and swore.

Bit by bit details of the escape leaked out, [...]

[excerpt]

One afternoon we were having roll-call on the overgrown tennis court outside the hospital. Five hundred men, women and children were in long lines, waiting for the Japanese guard and roll-call warden to arrive. Some were sitting on deckchair reading, others standing talking and laughing.

A school friend standing a few places away from me said to Brian, who was tall for his age and standing next to him, “I dare you to touch that wire.” Over our heads going diagonally across the field was an electrified wire, running from the power station to the guard’s watchtower behind us. Originally twenty feet from the ground, it had been sagging lower and lower in recent weeks.

Brian, standing with bare feet on damp ground, laughingly took up the challenge and touched the wire.

His fingers contracted around it. Letting out a desperate groan, he pulled the wire down to the ground; it narrowly missed dozens of fellow internees.

The following ten minutes were perhaps the most frightening in my life.

Panic spread throughout the group. Brian’s mother rushed to free him from the live wire, but someone thought quickly enough to hold her back, or she too would have been electrocuted. Screams and cries came from all sides, and pandemonium prevailed everywhere. Some calmer men slashed at the wire with their wooden deck chairs, which would not be conductors of electricity, and belatedly freed the victim, who was rushed in a lifeless state into the hospital, given artificial respiration but to no avail.

A shocked group of internees remained for the completion of roll-call formalities. For the rest of the evening, we waited outside the hospital in the hope that Brian would be revived, but it was not to be.

[excerpts]

[excerpts]

Social calls became popular. At roll-call, we made dates to visit each other to try the latest menus and recipes. The White Elephant swung into action again, and as we cooked over the hot cauldrons in Kitchen 1 we would overhear the latest exchange rates for Red Cross food: one packet of cigarettes could be bartered for two bars of chocolate, two tins of spam for one of coffee, and so on, according to the law of supply and demand.

The arrival of these supplies definitely saved the day for our community. Scrounging and quarrelling about rations and perquisites subsided as every family worked out its own method of spreading the food over as long a time as possible. Physical hunger and exhaustion were less acute, and with this the general morale was clearly lifted.

During 1945 we became more and more convinced that the war was turning in our favour in Europe and in our own theatre of fighting in the Far East.

[excerpt]

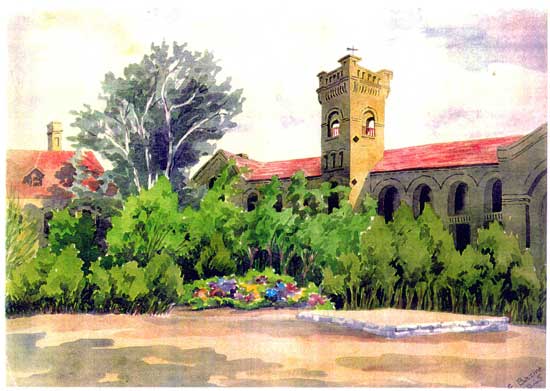

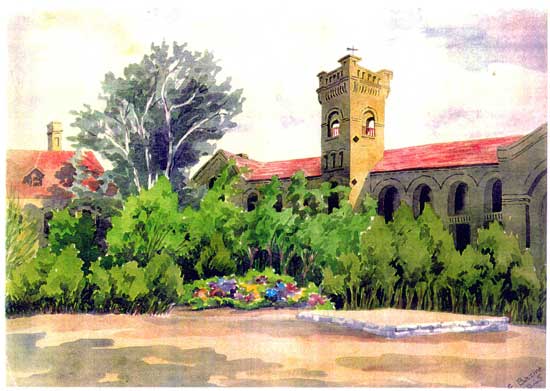

By this time I had moved back from the top floor of the hospital to a bachelor dormitory of Block 23, and was once again a roll-call warden. In the centre of this attractive building was the tower and bell which had been used in earlier days to call the Bible School students of the then American Presbyterian Mission to their classes. But now it was used by the Japanese to announce twelve o’clock noon every day, so that clocks and watches could be adjusted. In fact, it rang at 11.45 a.m. one day and at 12.25 p.m. the next. We could only conclude that for security reasons the Japanese did not wish us to have the exact time.

In the middle of a night in May 1945, we awoke rubbing our eyes. The Block 23 bell was ringing. We sat up in bed and speculated anxiously as to why the bell should be ringing at that unearthly hour. Was the Japanese war now over as well as the European one? Was there some kind of emergency?

Outside we could hear the heavy boots of guards, and shouts of anger in Japanese. Then a member of the Discipline Committee came in and said that everyone had to line up for roll-call outside in his or her usual group. Had some more fellow internees escaped?

As a roll-call warden for Blocks 23 and 24, I went to all the bachelor and spinster dormitories in the two blocks, passing on the instructions. I passed the message on to the Mother Superior at the other end of Block 23 — a number of American nuns in her room were sleeping under mosquito nets.

We lined up outside, not very wide awake. The Japanese guard counted us with a pistol in his hand, pointing at each person as he was counted.

His manner was abrupt.

We could hear shouting and orders being given out at some of the other roll-call groups.

As we tumbled back into bed the explanation for the crisis reached us. Months before V.E. Day one man had “dared” another that, as soon as the war in Europe was won by the Allies, his friend was to ring the tower bell at midnight. He had taken up the dare and carried it out. The Japanese were given the explanation for the bell ringing that same night, though the names of the offending internees were carefully withheld from them as recrimination would be certain and serious. But in spite of the explanation, the Japanese were still convinced that the bell ringing had been the signal for a further escape ? Hence the careful roll-call.

Another source of information about the war was a pro-Japanese English newspaper, printed in Peking and distributed in small quantities in the camp. The statistics of casualties, sinking of ships and destruction of aeroplanes were heavily loaded in favour of the Japanese, the intention being to convince us that the Allies were losing the war in the Pacific. But it told us more than that.

[excerpt]

ALARM AT WEIHSIEN

Incident of 5 May 1945

The camp lights had been extinguished at the usual hours, 10-p.m., and most internees soundly sleeping.

Just before 11-p.m. the startling sound of a rolling bell customarily used as the signal for roll-call, broke the stillness of the night and aroused the sleeping community. This was followed at a short interval by scurrying feet racing round the alleys, and the raucous sound of agitated Japanese voices and then the wail of a siren.

What could it all mean was the somnolent enquiry of many so rudely awakened from their slumbers: not the usual roll-call signal and surely not parade at such an hour. Perhaps an outbreak of fire or escaped internees!

What could it all mean was the somnolent enquiry of many so rudely awakened from their slumbers: not the usual roll-call signal and surely not parade at such an hour. Perhaps an outbreak of fire or escaped internees!

Voices in semi wakefulness were raised in protest against the speculative suggestions of those prepared for “a bit of fun”. “Let people sleep” was the angry retort of many, weary with a day’s heavy labour. Those anticipating an early call to duty next morning.

But sleep was not to be, for an order from the police chief was quickly conveyed to internees through the chief discipline officer for a roll-call outside blocks at once.

More grousing from sleepy voices, but eager anticipation from those with the mood for sound excitement. A weary wait for more than an hour in the cold of the early morning whilst the guards checked numbers only aroused further speculation and discussion of the alarming incident, ending in no more satisfaction than the hope of an early resumption of sleep.

“Did YOU ring the bell” was the query one met with throughout the camp the next day, and the usual discussion of the war news contained in the newspapers issued the previous day was completely overshadowed by the night’s events.

The mystery was still not solved until a threat of punishment by the authorities brought for the following confession:-

“The bell was rung by me last Saturday night as an expression of joy & thanksgiving for peace in Europe. I regret any unforeseen inconvenience caused to anyone.”

PEACE! Not yet for us but still the great joy and happiness of knowing that the Old Folks at home are at last released from the miseries and horrors of war and for us – NOT LONG NOW.

16/5/1945

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/Books/Courtyard/p-Frontcover.htm

#