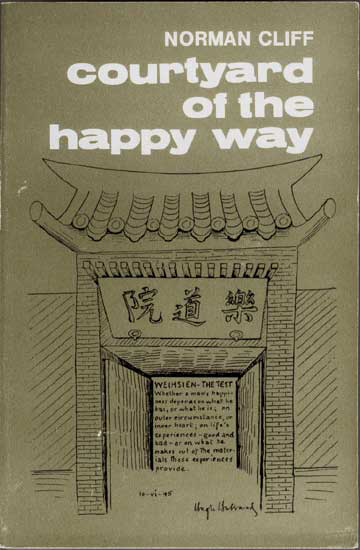

- by Norman Cliff

[Excerpts] ...

[...]

During the following year Mother and Father went on furlough to England, and my Christmas was spent at the school with other children whose parents lived in provinces too far away for holiday travel.

During the following year Mother and Father went on furlough to England, and my Christmas was spent at the school with other children whose parents lived in provinces too far away for holiday travel.

[excerpt]

Gradually the guards at the barrier thawed to the missionary children. They spoke to us in broken Chinese or faltering English. They showed us their bullets, photos of their sweethearts or families at home, and laughed and joked with us. We learned their names and began learning to count in Japanese.

[excerpt]

The months at Temple Hill dragged on monotonously.

Stocks of flour and coal often ran dangerously low to be renewed in the nick of time. Clothes were wearing out, and children were outgrowing what they had. Dresses and shirts were made from curtains brought to camp. We were learning to improvise in a hundred and one ways.

[excerpt]

But when the ship’s siren sounded, the baker had not arrived. The vessel began to glide out of the harbour. The headmaster had visions of a shipload of frantically hungry schoolchildren crying out for food. But the ship stopped in the harbour. A launch was making its way from the docks towards us.

The determined baker had secured transport for his important cargo of food. The bread aboard, we slipped out of the harbour in front of the Bluff towards the open sea. Across the water was the whole port of Chefoo ― the place of my birth eighteen years before, the scene of my upbringing for the previous twelve years, including a year’s internment. Few could lay greater claims to this port as being home.

[excerpt]

The womenfolk and younger children were packed into buses. I jumped on the back of a lorry piled high with luggage. We rattled and bumped along a dusty road for several miles past Chinese farm fields. What we gathered must be Weihsien Camp sprang into view. Rows of juniper trees, long lines of dormitory blocks, the red-tiled roof of an Edwardian-style church ― all surrounded by a wall with electrified wires and with cement boxes here and there.

[excerpt]

Their departure had left a vacuum in effective manpower for such tasks as pumping, cooking and baking. Thus the arrival of our Chefoo community aggravated the situation further, for out of the three hundred of us only about two dozen were potential camp workers, the remainder being schoolchildren and retired missionaries.

[excerpt]

Included in this small group of keen Hebrew students was an Irish boy, Brian Thompson. Several years my junior, he was the life and soul of the group, always up to pranks.

His mother was on the school staff, and he was the eldest of a line of young children.

One afternoon we were having roll-call on the overgrown tennis court outside the hospital. Five hundred men, women and children were in long lines, waiting for the Japanese guard and roll-call warden to arrive. Some were sitting on a deckchair reading, others standing talking and laughing.

A school friend standing a few places away from me said to Brian, who was tall for his age and standing next to him, “I dare you to touch that wire.” Over our heads going diagonally across the field was an electrified wire, running from the power station to the guard’s watchtower behind us. Originally twenty feet from the ground, it had been sagging lower and lower in recent weeks.

Brian, standing with bare feet on damp ground, laughingly took up the challenge and touched the wire.

His fingers contracted around it. Letting out a desperate groan, he pulled the wire down to the ground; it narrowly missed dozens of fellow internees.

The following ten minutes were perhaps the most frightening in my life.

[excerpt]

When we arrived in Weihsien children from Peking and Tientsin already had a school running, largely a continuation of the Tientsin Grammar School. But in mid-1944 discipline was low and studies for this group were grinding to a halt.

The camp Education Committee cast envious eyes at the Chefoo school group, with its well-behaved scholars and smooth-running academic programme. The result was that two Chefoo masters and I were approached to reorganise the Weihsien School ? a change which immediately put it on a new footing. I was given a class of eight-year-olds to teach. We sat in one wing of the church. The group under me included White Russians, Hindustanis and Eurasians. It was a happy experience and the children seemed to get on with their studies with renewed zeal.

[excerpt]

Soon life in this new camp was running smoothly and we were feeling very much part of this new social environment. I was housed with other boys of the school in Block 23, an attractive building at the far end of the camp, superior to the small blocks of rooms in which the families were housed. The Labour Representative placed me in a kitchen shift of Kitchen I that fed some six hundred people.

Our mode of life was simple and primitive.

The day began with filling buckets at the pump for purposes of cooking and washing. Firewood was collected from trees and bushes, and used in the stove in the middle of the room. From this, water was heated for shaving and washing, and at a later stage for cooking breakfast, that is whatever we had privately for supplementing the official rations. We queued up in Kitchen I for a ladle of bread porridge and some bread. Into our mugs was poured black tea ladled out of a bucket.

Back we went to the bedroom to mix the kitchen issue of food with our own dwindling resources in the most enjoyable combination possible.

Then followed washing of dishes, cleaning of rooms, hanging our mattresses in the sun in a bid to kill the bed bugs, washing our clothes, hanging them out to dry, and so on.

[excerpt]

Then, in addition to problems with hygiene, pilfering and labour was that of keeping the education going of those who, had they not been in camp, would still have been at school preparing for Matriculation.

The Chefoo school on moving to Temple Hill, then to Weihsien, had kept its identity as an educational unit, and to a remarkable degree had maintained a regular programme of studies; in spite of limited supplies of textbooks, paper and other necessary materials they had kept abreast of their prescribed syllabi, leading up to the Oxford School Leaving Certificate.

[excerpt]

It was quite evident that the four hundred Catholic priests and nuns had made a great impact and profound impression on the internee community. They had turned their hands to the most menial tasks cheerfully and willingly, organised baseball games and helped in the educational programme for the young.

But inevitably romances had been formed between admiring Tientsin and Peking girls and celibate Belgian and American priests from the lonely wastes of Manchuria. Anxious Vatican officials had solved the delicate problem by careful negotiations with the Japanese, as a result of which all but thirty priests had been transferred to an institution of their own in Peking where they could meditate and say their rosaries without feminine distractions.

[excerpt]

Christmas came. We bought small presents for each other at the White Elephant, made little gifts from our limited supplies of wood, cloth and paper. We had games and parties, as well as a joint Christmas service in the camp church.

A group of us went from block to block on Christmas Eve singing carols, and we invariably ended each visit with this significant postscript:

“We wish you a merry Christmas,

a merry Christmas,

a merry Christmas;

We wish you a merry Christmas,

and a Happy New Year,

And hope it won’t be here!”

Imagine our surprise and amusement when on Christmas Day a Japanese guard off duty walked happily down the main road from the guardroom, singing merrily:

“Ha, ha, ha, hee, hee, hee,

Elephants nest on a rhubarb tree,

Ha, ha, ha, hee, hee, hee,

Christmas time is a time for me!”

[excerpt]

A guard off duty invited me to play him a game of chess. He took me to the officers’ quarters at the far end of the camp from the gate ? a part I had been to only once previously to sweep and spring clean some houses for Japanese officers moving in.

I sat in his room and looked round his abode simple, clean and cheerful. A picture of his sweetheart was on the wall. Uniforms were hanging up in the window to dry in the summer sun. He passed me a “ringo” (apple) as we played. It was hardly an inch and a quarter in diameter. I devoured it, small though it was. It was the only fruit I had tasted during the two years in Weihsien camp.

Playing chess proved to be a most effective way of diverting one’s mind from the trials of those days — the shortage of food, the possibility of a Japanese victory in the Far East and the frustration of losing valuable years of one’s life in internment.

Thus when off duty I went the rounds of certain chess enthusiasts and played for hours. The intricacies of the game so absorbed my mind that fears and forebodings were temporarily squashed.

Another pastime for me was learning French conversation. I had learned to read and write French, and had had good results in my Matric exams.

Now it was the opportunity to put theory into practice. The Belgian priests working alongside me in Kitchen 1 spoke French frequently to me, while I in turn helped them with English. Several evenings a week I went to the bachelor quarters of a Mr. Dorland for French conversation. Sitting on his porch in the dark (there was no electricity in the living quarters) we discussed architecture, theology and camp life in general. Rumour had it that Dorland was a spy for the Japanese, and so I steered the conversation along uncontroversial lines.

N.D.L.R. from Leopold Pander:

... in fact, Mr. Dorland — as written in the text above — is Father Emmanuel Hanquet, a Catholic missionary in Weihsien. He told me what really happened, many years later when I was assembling the various parts of this present website about Weihsien. It is also thanks to Emmanuel Hanquet who convinced Norman Cliff to trust me using all his scrapbooks about Weihsien for the veracity of all you are reading within.

...

[... the same story]

... in fact, Mr. Dorland — as written in the text above — is Father Emmanuel Hanquet, a Catholic missionary in Weihsien. He told me what really happened, many years later when I was assembling the various parts of this present website about Weihsien. It is also thanks to Emmanuel Hanquet who convinced Norman Cliff to trust me using all his scrapbooks about Weihsien for the veracity of all you are reading within.

...

What good has come from Weihsien ?

by Gordon Martin

It was good that missionaries and business people should live together. Both sorts live in China absorbed in their own lives there is usually little intercourse and too much feeling of difference. In internment camps, missionary and business man were neighbours, knowing each other’s ways and temper; sharing camp duties, sweeping, carrying garbage; standing in the same queues, silent queues, impatient and resentful queues, talkative, cheerful queues; seeing each other take hardship or responsibility. Many of us are very grateful for the chance of knowing fine men and women from the business world, whom we should never have met but for internment.

Then what a chance to meet our missionary partners ! The whole missionary body of North-East China was in Weihsien, except for German or neutral missionaries. We were of different denominations and diverse in outlook; but we had a Weihsien Christian Fellowship, a Fellowship in spirit as well as in organisation. In this matter we owed very much to Harold Cook, of the Methodist Missionary Society, and to Bishop Scott (S.P.G.). We all had a chance of enrichment, and we shall have friends everywhere, as a result of internment.

These new contacts made possible new duties.

We from Chefoo were no longer living in a small largely feminine community. We had to work with men and commend our Gospel by being active and efficient. Some of us were Wardens looking after the needs of people in our blocks ; others were cobblers, bakers, butchers. Gordon Welch became manager of the camp bakery - a vital function! - and for a long time he served on the most difficult of the camp committees, the Discipline Committee. Managing the games for the camp, running a Boys’ Club in the winter, running Scout and Guide activities, and many other tasks gave us new chances of being useful. Cleaning vegetables, issuing stores, managing the sewing room, mending clothes were less interesting tasks : but all meant new contacts; and new contacts and necessary tasks were for our profit.

As I think about the Chefoo boys and girls in the camp, what was their gain? We know that their book learning was curtailed, that they went through considerable discomfort, and that they were tested severely in character. Some minds have been contaminated, early training has been shaken, standards have become uncertain or lowered. Close contact with men and women of every sort has opened the eyes of our boys and girls: they have seen dishonest and vicious people; they realize how widely diverse are the standards of conduct and amusement, even among people of upright life; they have seen many varieties of Christian life and worship. To assimilate so much experience was not easy without some upsets. But in these matters they are the better fitted by these experiences to enter the adult world of their home countries. And tests are God-given: we do not know the end of these testings.  To counterbalance those boys and girls whom we think of as defeated, we look at others who not only survived the tests, but triumphed; who were shaken, but ended with their convictions settled on the Rock. I believe that most of our boys and girls will be stronger for life because of Weihsien.

In self-reliance, in manifold abilities they have gained greatly: cooking, stove building and tending, household duties are familiar to them. To choose their own occupations, their own reading, friends, way of spending much of Sunday, the fashion of their private devotions - these choices have been forced upon them by circumstances. For choosing adult careers, they are better equipped both by what they have done and by the contacts they have had, than by the ordinary training of school and college.

To counterbalance those boys and girls whom we think of as defeated, we look at others who not only survived the tests, but triumphed; who were shaken, but ended with their convictions settled on the Rock. I believe that most of our boys and girls will be stronger for life because of Weihsien.

In self-reliance, in manifold abilities they have gained greatly: cooking, stove building and tending, household duties are familiar to them. To choose their own occupations, their own reading, friends, way of spending much of Sunday, the fashion of their private devotions - these choices have been forced upon them by circumstances. For choosing adult careers, they are better equipped both by what they have done and by the contacts they have had, than by the ordinary training of school and college.

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/Aftermath/GordonMartin/p_GordonMartin.html

and:

[further reading]

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/NormanCliff/Books/Courtyard/p-Frontcover.htm

#