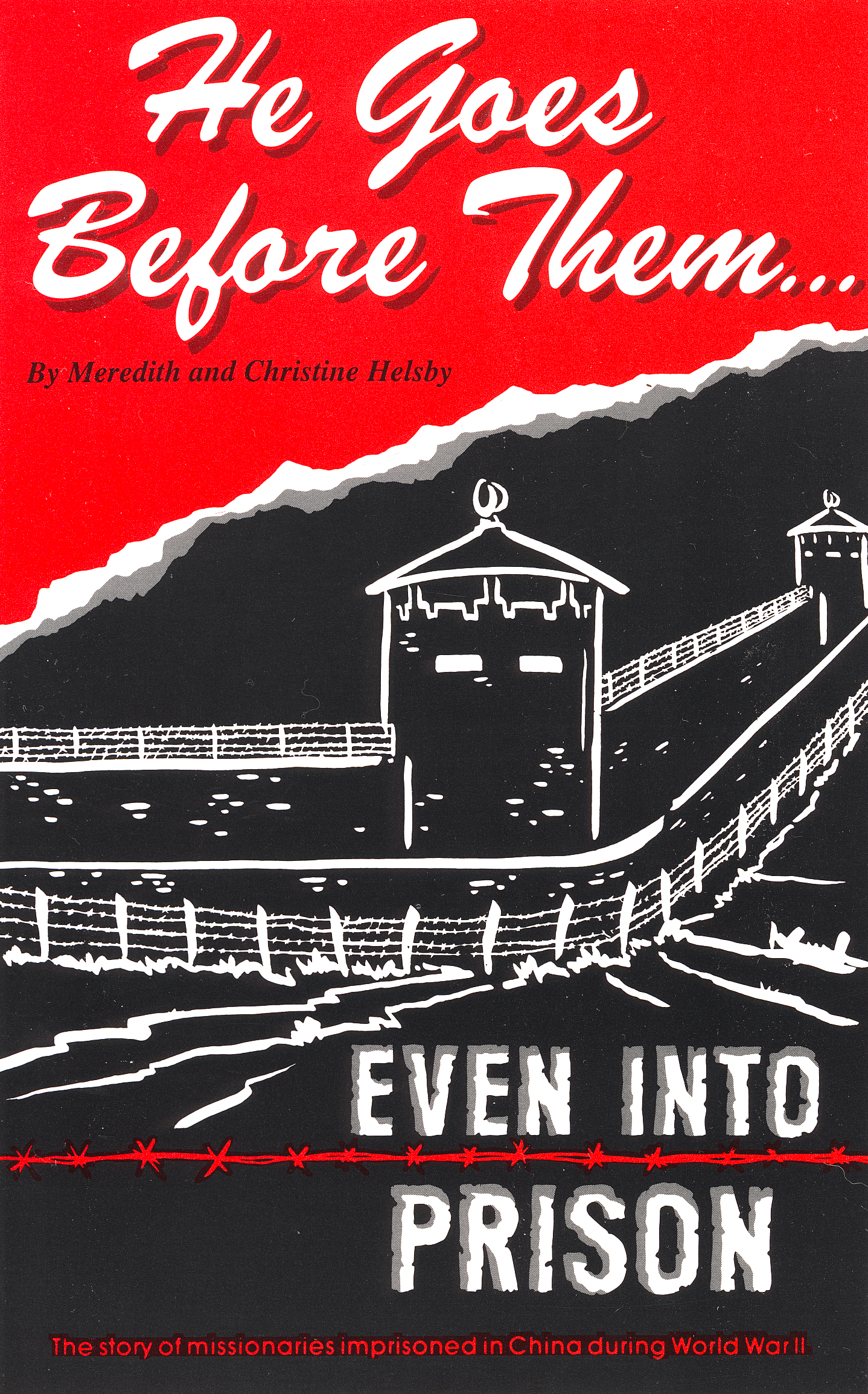

- by Meredith & Christine Helsby

[excerpts] ...

[...]

or the most part, the guards’ treatment of us was marked by decorum and good discipline, and efforts were made to observe the articles of the Geneva Convention governing treatment of civilian prisoners of war. A few, like Mr. Kogi who had studied in a mission school, had come in contact with Christianity in Japan and went out of their way to treat us with consideration and courtesy.

or the most part, the guards’ treatment of us was marked by decorum and good discipline, and efforts were made to observe the articles of the Geneva Convention governing treatment of civilian prisoners of war. A few, like Mr. Kogi who had studied in a mission school, had come in contact with Christianity in Japan and went out of their way to treat us with consideration and courtesy.

Still when our captors, small of stature and looking almost like children beside a 6 foot 2 inch American or Englishman, felt intimidated they could respond with unfeigned arrogance or fly into a rage barking, ranting, gesticulating, slapping and kicking. When in dress uniform these diminutive men strutting back and forth, their long Samurai swords trailing in the dirt, looked so much like small boys at play it was hard to suppress a smile.

Smiling or laughing in their presence, however, is something we early learned to avoid — as this was often taken as a sign of contempt, insolence or lack of respect, inviting angry reprisals and threats.

Among 70 men of any nationality one will, of course, discover tremendous diversity. And while some of these guards early identified themselves as friendly, others we soon learned to give a wide berth. A few acquired interesting nicknames.

The commandant, a heavy scowling man of surly disposition, was soon dubbed “King Kong.”

Another officer, who looked like the Japanese counterpart of Sergeant Snorkle, took a perverse delight in squelching any activity which appeared suspiciously like fun. The sight of an internee sunbathing or a couple holding hands would elicit a growled “Pu Hsing Ti.” (You can’t do that!)

Another officer, who looked like the Japanese counterpart of Sergeant Snorkle, took a perverse delight in squelching any activity which appeared suspiciously like fun. The sight of an internee sunbathing or a couple holding hands would elicit a growled “Pu Hsing Ti.” (You can’t do that!)

Soon he had earned the moniker Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti. Before long wherever this gentleman appeared, he was greeted by throngs of small children who followed, dancing up and down chorusing, “Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti, Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti.”

This was most disconcerting, of course. So much so that the man appealed to the commandant, and a short time later the following announcement appeared on the camp bulletin board:

“Henceforth in the Weihsien Civilian Center, by special order of His Imperial Majesty, the emperor of Japan, Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti is not to be known as Sergeant Pu Hsing Ti but as Sergeant Yomiara.”

[excerpt] ...

Life is full of surprises, and we soon learned it was a mistake to judge the Japanese by their appearance. One internee described a surprising encounter with a menacing-looking guard:

It was with great apprehension that we saw one afternoon at tea time one of the soldiers, loaded down with every kind of portable weapon, approach a building where, among others, an American family with a baby was housed. I was the only male present at the time.

Gingerly I opened the door at the guard’s brisk knock. He bowed and sucked air in sharply through his teeth. Then unloading his extensive armor, to my utter amazement he opened his great coat and pulled out a small bottle of milk.

“Please,” he said haltingly, “take for baby.”

After we had recovered from our surprise sufficiently to invite him to come in, we asked whether there was anything we could do for him in return.

“May I hear classical records?” he asked. Again we gasped and said, “Who are you?” He answered, “I, second flutist in Tokyo Symphony Orchestra. Miss good music!”

[excerpt] ...

One of the most pressing concerns in the early days of camp was continuing education for the children. After the entire faculty and student body of Chefoo (the China Inland Mission School for missionary children) arrived at Weihsien in the fall of ‘43, we had more than 400 youngsters under age 18 in our community.

Organizing classes for all the students, kindergarten through 12th grade (the responsibility of the education committee), was a Herculean task indeed. There were virtually no textbooks or equipment and the only regular classrooms on the compound were of necessity being used as dormitories. The dedication and resourcefulness of teachers and staff were a marvel to behold. Yet, regular classes continued until our liberation, and three classes of seniors actually took the Oxford Matriculation Exam.

Many of the students in Chefoo boarding school, when war broke out, were separated from their parents. The teachers were more than ever now not only instructors but surrogate parents, a responsibility they did not take lightly. This noble corps of missionaries resolved that even in prison camp, under the most appalling conditions, they would not relax standards of decorum and good breeding one whit.

[excerpts] ...

Sandra, along with the other children, was allotted about two eggs a month or as the Japanese could obtain them. To prolong the pleasure and nutrition of these treasures, Christine fashioned a concoction by mixing the egg with “tang shi” (kaoliang molasses). Used as a spread to top our bread, the food value of that egg could be extended several days.

To supplement the bone meal which we brought into camp (but ran out of almost a year before we were freed), we pounced upon eggshells discovered on a trash heap, dried them for days on our window sill, then rolled them as finely as possible with a glass. Sandra consumed about a quarter teaspoon mixed daily in her food. (Her adult teeth are now as strong and beautiful as any whose childhood was spent in “replete” America.)

There was a critical need for milk, especially for small children. When the commandant was appealed to, surprisingly he arranged to have a quantity of milk brought regularly into camp. This was properly sterilized in the hospital kitchen and distributed to children under three years of age, enough for each child to have about a cup of milk daily, though not available every day.

[excerpt] ...

Situated throughout the compound were unspeakably foul, open cesspools, dug to receive the waste produced by our camp’s 1800 residents.

As we have mentioned, periodically these pools were emptied by Chinese coolies with their “honey buckets.” Why a child would choose the vicinity of a cesspool for a playground is a mystery beyond the ken of any adult. Yet, it is the nature of children to be oblivious to many things that their elders find impossibly distasteful. And so it was that John and Mary Kelly had chosen to play on the low, stone rim of the cesspool situated not far from kitchen number one.

Johnny’s father was a British missionary who worked in Mongolia. There he met and married a Chinese woman. The whole family lived “native style”, wearing Chinese clothes, eating Chinese food and speaking very little other than Chinese. In camp they kept aloof from most of the missionary community.

How it happened no one seemed to know for sure, but the fact is, Johnny fell head first into the loathsome pool. The frantic cries of his sister, Mary, brought men working in the area to investigate.

One of these was our dear friend, John Hayes.

Kelly had gone under and bobbed up the fourth time when Hayes plunged into the pool to rescue him, thus averting another camp tragedy. It was inevitable that little Johnny, thereafter, was always referred to as “Cesspool Kelly.”

And thankfully, neither Johnny nor our friend, John, seemed any the worse for their cesspool “baptism.”

[excerpt] ...

During the two-and-one-half prison years, the camp was devastated by succeeding epidemics of dysentery and hepatitis. Others suffered from severe mental disorders. Despite the handicaps, doctors performed many major operations, among them a good number of deliveries.

There were 32 children born during our years in camp, and in that same time 28 people died.

Many of these were elderly, who without sufficient nourishment grew weaker and weaker. The father of our friend, John Hayes, was one of the elderly who died early in camp. But all the victims were not the elderly and fragile. Clarice Lawless was a young, uncommonly robust woman who lived three doors down from us. She led the Chefoo girls in calisthenics every morning on the softball field. Yet Clarice was taken down by typhoid, surviving only eight days after she was stricken.

[further reading] ...

http://weihsien-paintings.org/GordonHelsby/photos/p_FrontCover.htm

#