- by Sr. M. Servatia

[excerpts] ...

[...]

The Commandant of the Camp, Mr. Sukigawa, spoke fairly fluent English, having previously held a consular position in Hawaii. I think he tried his very best to keep away any friction between us and the guards.

The Commandant of the Camp, Mr. Sukigawa, spoke fairly fluent English, having previously held a consular position in Hawaii. I think he tried his very best to keep away any friction between us and the guards.

The guards, being in Consular Service, fared far better than those in the war areas, but they were changed occasionally although none of us knew how often or for what reason. Mr. Ibara was the Commandant’s aide. He was more straight-laced than was Mr. Sukigawa, but like the guards I am sure he appreciated the position he had.

During that first week papers were being sent around, asking us what work we were most interested in.

While we were at the camp, we did not know how long we would remain and some thought that perhaps the Japanese would in time send us over to Japan and we would have to work for them at their pleasure. As a result, this form caused us some concern. We did not realize that the paper was coming from our own side and certain people of the camp were trying to get organized. There was much work to be done, particularly because there were few conveniences.

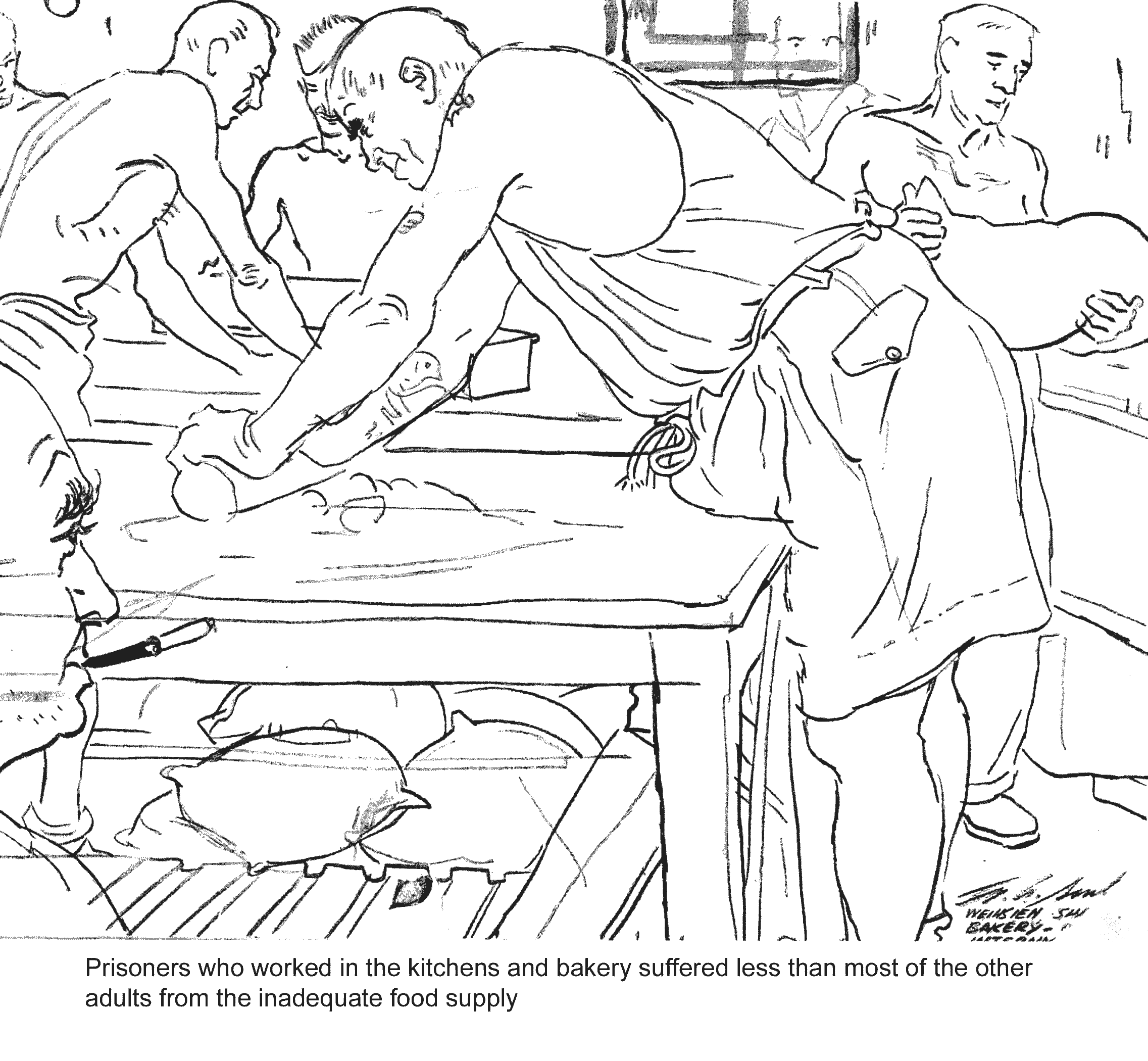

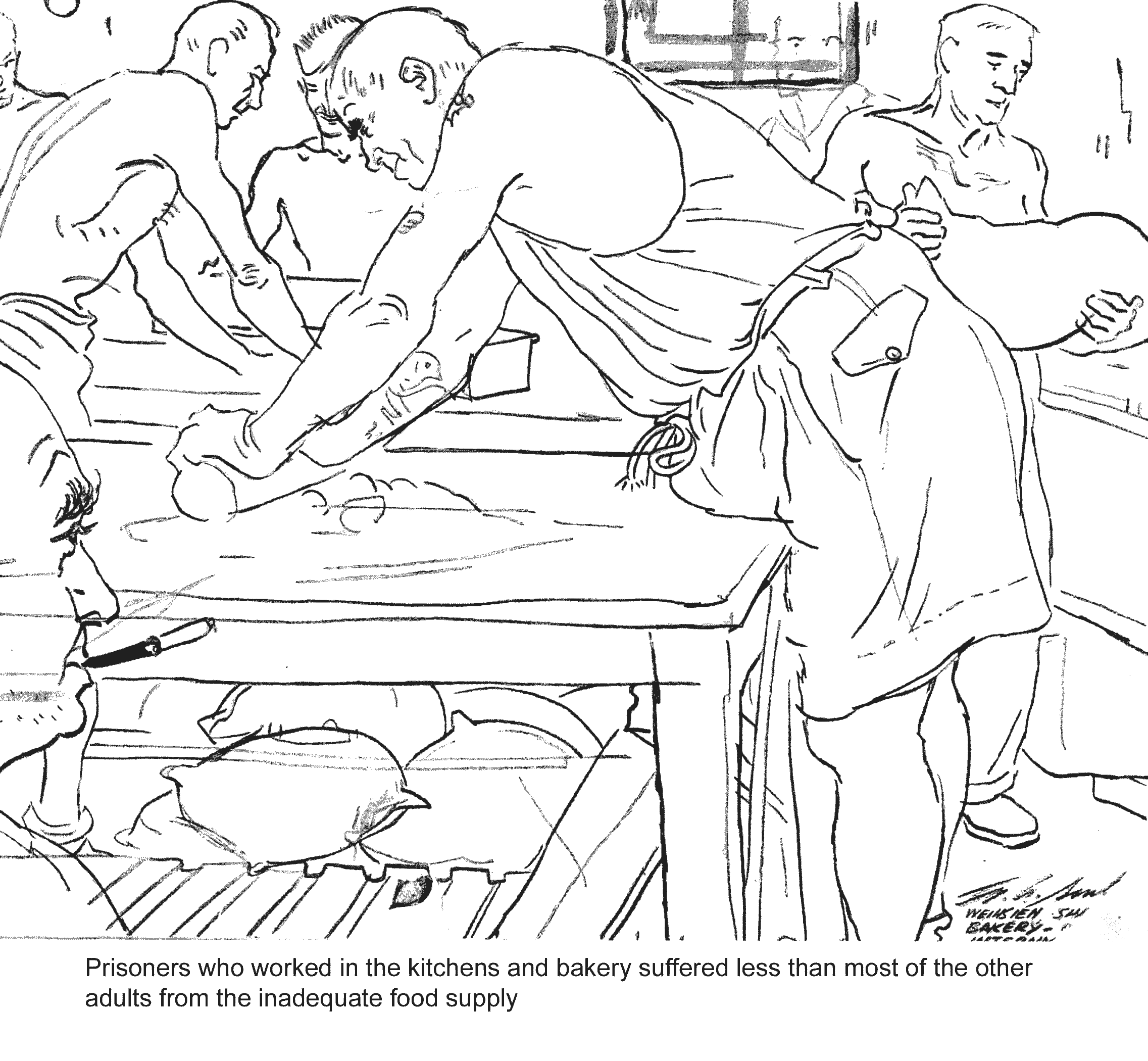

Water had to be pumped by a steady shift of men at several pumps. Cooking and preparing of vegetables, meat, fish was also necessary. The bakery was a problem. The hauling of coal, care of the lavatories, teaching of the children, washing, keeping the grounds clean, etc., etc. were all vital chores.

I signed up for kitchen duty and got it. Each person in the camp was required to perform at least three hours of camp duty. In no time the labor committee organized the camp.

[excerpts]

[excerpts]

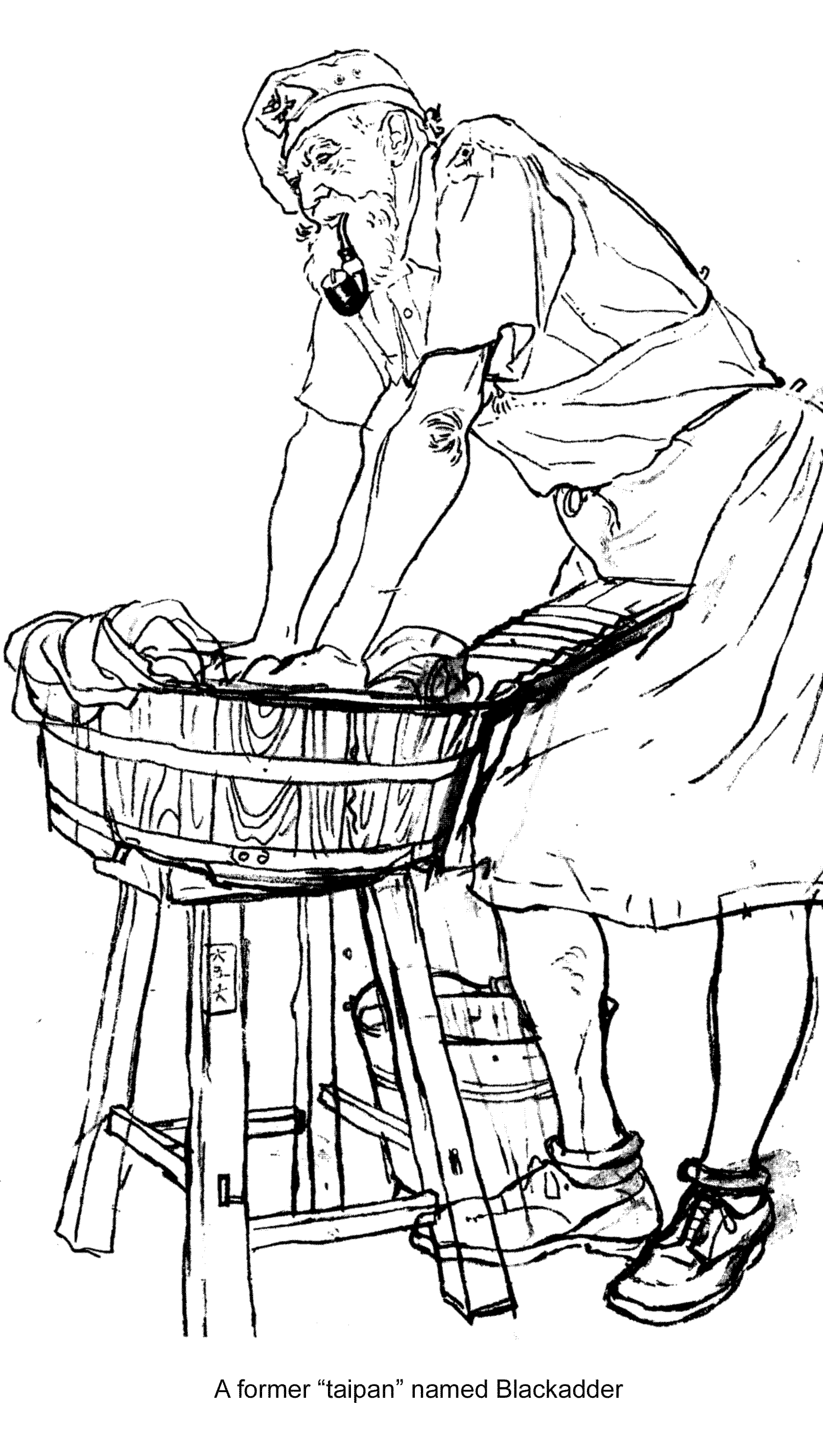

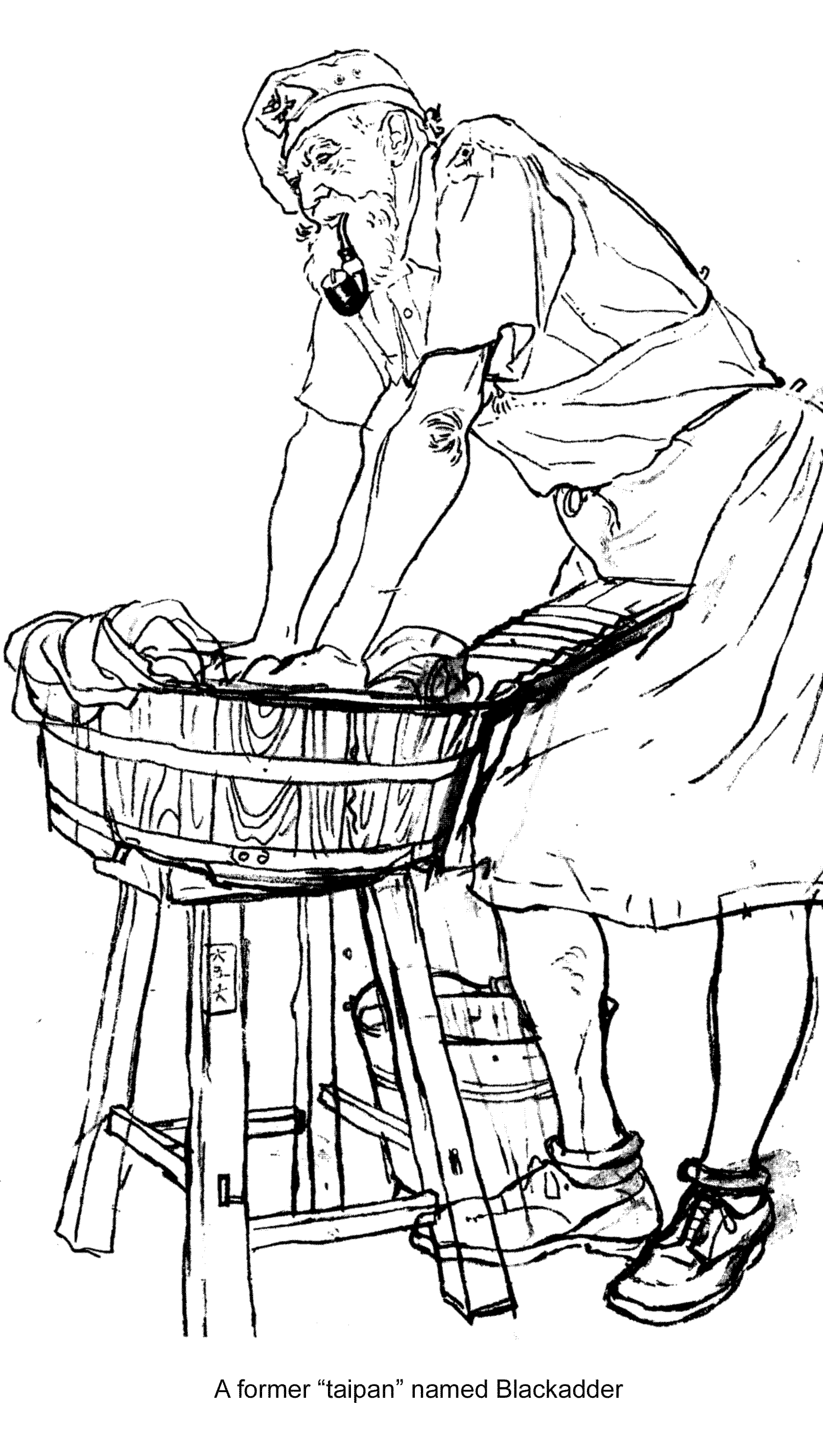

The next week Sr. Reginald asked Sr. Esther if she could do the washing for the five Trappists. There was enough to keep us busy, crowded as we were, but Sr. Esther said she could, on condition that she asks none of us to help her. I felt sorry for her because I thought the washing for five men would be too much so I offered to help. She went over to get the sheets and other wash and came back loaded down. Father Scanlon offered to carry the water and Sr. Reginald managed to find someone who would lend her a twenty-four-inch basin and I took our two basins along and we found a place outside to wash. The sheets were made of a material almost like canvas and we wondered when they had been washed last. Sister managed to borrow two scrubbing brushes and together we scrubbed. I had only a small basin so I could scrub about a six-inch square at a time, but we felt we were doing good work so we might as well enjoy it while it lasts. Each week after that we did their washing, with Father Scanlon standing by to get us hot water from the boilers about two blocks away. And while we scrubbed, he would talk.

One day Sr. Reginald got tired because she couldn’t scrub and listen intently at the same time to his Australian dialect, so she told him to please go away. He was hurt and so after that he sent Father Alphonsus L’Heureux instead.

[excerpts]

The leeks were interesting things. They were about two feet long, and of course, mostly greens, which the one in charge said were to be cut off and put into the garbage. Gradually we began to recognize the value of these greens and used them in Kitchen One.

One day we found Sr. Ludmilla trying to fry onion tops with some potatoes she had gotten somehow. On being asked where she got those from she said, “from Kitchen 3’s garbage box”. She had taken them from the top of the bin and washed them off.

One day I happened to be working alone in a room outside the kitchen chopping the tops off. I had a bunch cut off and when I turned to them, they were gone. Mr. Echford was just snatching them away. The British ex-Consul of Peking and here he was scrounging onions! He said, “Doctor’s orders!” and left. I did not respond as it was better not to say anything about it.

Cleaning of the vegetables was a job for the ladies and we had ladies at it who perhaps hadn’t ever done it before in their lives, and now for want of something else, they got that job. They willingly peeled the potatoes and clean the vegetables but when it came to the leeks, there was always trouble.

That seemed to be something too demeaning.

Some generous soul had donated two potatoes paring knives but it didn’t take long and we had only one, then none. We were given a few knives for use on the vegetables, but the one in charge had to guard them with hawk eyes because they were precious things.

It was the men’s duty to bring the vegetables to the kitchen and also to wash the potatoes.

Outside the kitchen were two bathtubs which we figured, the army personnel had taken out of the houses in “out of bounds” because they preferred showers. The men were to fill them with water from the well and scrub the potatoes for the ladies to peel. Brother McCoy got that job and he hated it. I gently reminded him of what he said about not having anything to do in a concentration camp and he advised me that his opinion had changed.

[excepts]

[excepts]

One of the worst jobs in camp, although there were many other unwanted ones, was cleaning fish. We finally got a little crew together. Sr. Mercedes and I, three of the Protestant missionaries and perhaps one or two others. Each time the fish came in we would be alerted and we clung to the job and if the rest didn’t want to do it.

. . . well let them go hang. In winter it wasn’t less pleasant because the fish were packed in huge boxes of ice and we had to pull them apart and besides the work had to be done outdoors on an old table. It was always interesting to note the different kinds of fish that came out of the box and sometimes we wished one of us had studied fish before we came because there were varieties none of us had ever seen before, even baby octopus.

[excerpts]

The lavatories must have been a problem to those who were preparing the place. Generally speaking, Japan does not have lavatories such as we have in the States. The ones in the camp were in separate buildings, the men and women each having their own. Each building had about eight toilets, separated by a wall. On top was a water box for flushing, but since all water had to be pumped and there were so many to use them, it took about three days and these boxes were useless from then on, which meant that it had to be periodically flushed with pails of water.

There were no seats, just an elongated, enamel bowl on the floor about a foot wide. The matter was flushed to a place outside the room and Chinese were allowed to come and remove to their fields where it was used for fertilizer.

Cleaning these places was another duty not to be envied and it was finally resolved that all ladies take their weeks for the W.C.’s and men for the M.C.’s.

Sometime in the beginning of 1945 the Japanese got in a long urinal along the other wall of the room. We wondered why and finally it was thought that since in Japan there is no distinction between men’s and women’s facilities they expected the men to use ours too, but we dared them and there was no challenge.

[excerpts]

The next thing we needed was a diet kitchen with food of a little better quality for the sick, so one was organized. Mrs. Wormsby was put in charge, and she was good because she could put everybody under her in their place, whether you liked it or not. Rough as she was, I finally got to like her. I was placed in charge of dining room service and she told me just how much to give each so there was something left over and I could give seconds. The work wasn’t hard since I only had to be there at meal times. Several of the Fathers had jobs around the kitchen and dining room. Father Corneille Louws, a Dutch priest and Superior of the mission of Yungping, was under me and the tables were his job. I was the boss of a Superior, and Mrs. Wormsby told me in no uncertain terms I shouldn’t be afraid to tell them what to do. One of the Trappists was sick for a few weeks and Father L’Heureux would come to get his ration for him. He would bring the little bucket, stand it down for me to fill, and then go out. Sometimes it was late when he would return. One day we were all finished in the dining room and Father had not returned. I took the bucket and walked the three blocks over to the Trappists house, knocked at the door. Someone inside said:

“Ching!” (“Enter”—in Chinese) and there sat the sick Trappist on his bed eating his ration from the kitchen which one of the Fathers evidently brought him, and it looked like a proper portion to me. I spoke a few words in Chinese but he didn’t understand. I gave him the dinner and left.

[excerpts]

One of the White Russian ladies requested an English teacher. She didn’t want to attend classes so I went over to her room a few times a week.

Her husband, Johannes Johannsen, had been a sea captain, and had travelled around the world working in different countries. He was quite ill, but he loved to have company and I often thought that was his wife’s main reason for not wanting to leave him alone while she went to class. He had many stories to tell and he used to joke about the fact (and we all knew it was true enough) that he had always felt best on sea and now that he had to stay on land, he was ill, while it was just the opposite with the rest of us. The English lessons were interesting indeed. I listened to more sea stories than she to English. The captain got gradually worse and finally passed away.

I continued teaching and one day she told me that she had come to China with her ex-husband to escape the Revolution in Russia but later they separated. Then she met the captain and married him. She had a servant girl in Shanghai, also a Russian, who married, and later left her husband and married another. She scolded the girl for doing so, not realizing that she herself had done the same thing.

Probably she thought because she was of a higher class, it didn’t make so much difference. One has to marvel at the way the faith of the Orthodox Church is handed down from generation to generation. Although most of these didn’t care about Sunday services, still there must be Baptism, weddings and funerals according to the rites of the Church.

[excerpts]

It was said that Goyas made a million dollars on the black market while in Weihsien, but even if that were so, when eggs were $5.00 apiece, a million dollars wasn’t what it was at that time in the States. It was also said that he had four passports and we all believed that story. One night we were awakened by a noise in the little corridor outside our room. It was a hot summer night and we had not locked the door; there was just a little sliding half-door which was hooked. Then a loud knock on Sr. Eustella’s door. There were a few more quiet noises and all was still.

In the morning I asked Sr. Eustella about it and she said the guards most likely were after Goyas again and that our quarters were one place he thought it was safe for hiding. The Japanese would not easily come into the nun’s quarters.

But try as the Discipline Department could, they could never stop the scrounging any more than they could stop the breathing of the camp.

Those who worked in the bakery took home flour, those in the kitchen meat, and the ladies at the vegetables stuck some vegetables in their pockets. It was nice to have a job where you had a chance to scrounge something to cook on your little stove at home, and it just meant somewhat less in the dining room and fewer seconds.

[further reading]

http://weihsien-paintings.org/books/Servatia/Servatia(WEB).pdf

#