by Pamela Masters, née Simmons

Chapter 13

[excerpts] ...[...]

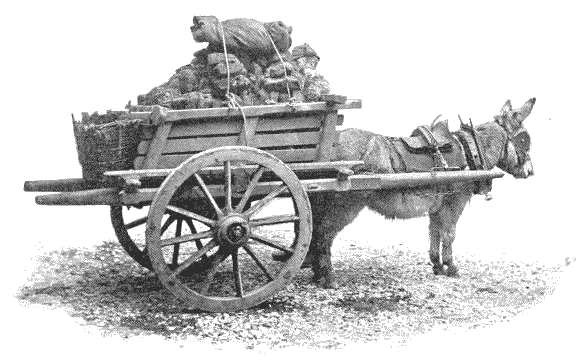

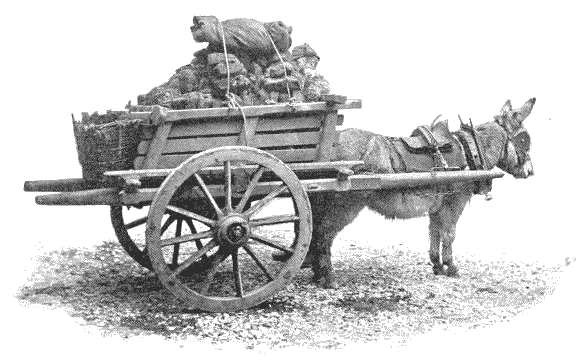

Then, one day in mid-January 1945, when snow and sleet were coming down to add to our misery, the main gates were dragged open, and a line of donkey carts loaded with Red Cross parcels started weaving and side-slipping up the grade!

Then, one day in mid-January 1945, when snow and sleet were coming down to add to our misery, the main gates were dragged open, and a line of donkey carts loaded with Red Cross parcels started weaving and side-slipping up the grade!

I stood in total disbelief as load after load came into the camp. In my excitement, I hadn’t noticed the crowd that had gathered around me until Pete Fox picked me up and spun me around shouting, “Now do you believe in Santa Claus?!”

“They say American Red Cross, like those back in July,” I said, remembering the handful of parcels that had come in the previous year and been doled out to the Americans.

“Yeah, but I counted a hundred boxes on each cart. And there were fifteen carts; that’s more than enough for every one of us in camp!”

Pete had to be right—these parcels were for all of us! So Christmas was late, so what!?!

“Yeah, but I counted a hundred boxes on each cart. And there were fifteen carts; that’s more than enough for every one of us in camp!”

Pete had to be right—these parcels were for all of us! So Christmas was late, so what!?!

I found myself dreaming of their contents, and the anticipation was delicious. I knew what I needed: soap. And, luxury of luxuries: toothpaste. I knew what I wanted: tea, coffee, and maybe some candy; my craving for something sweet was almost unendurable. I would have loved eggs and butter, but knew they were perishable items that could not stand weeks and months in transit. I dreamed on and savored every minute it.

Strangely, the parcels arrived with no instructions, and as there were just over fourteen hundred internees left in the camp now, including two hundred Americans, the Commandant posted a notice stating that the parcels would be given out the following day, one to each internee, and one-and-a-half to each American.

His orders didn’t prevail though. He was mobbed by a contingent of angry Americans, who stormed into his office and told him that those parcels were for them and no one else, and that he had no right to give away American property; it was not his to give.

I was with Dan when we learned of this turn of events, and he was sick and disgusted with his fellow men. “What the heck would my Mom and I do with fifteen comfort parcels!” he exploded. “How could we possibly enjoy them while all our Allied friends were going without.

This is ridiculous! I bet, if they polled the Americans, they’d find most of ‘em want everyone to get a parcel.”

Dan was wrong though. The generous Yanks had made an about-face, and even if the majority didn’t like the stand that had been taken, they backed the group that made it, stressing the parcels were American property and reiterating that they were the only ones entitled to receive them.

Afraid of an uprising, the Commandant took immediate control and had all the parcels locked up until he got instructions from Tokyo.

While we waited for them, the camp that had once been tolerant of all the different nationals, became bitterly divided.

The ensuing two weeks had to be the slowest I’d ever known, and when the instructions from Tokyo were posted—just in time for my eighteenth birthday—they stated that every American and Allied inmate would get one comfort parcel; anything over would be sent to another camp.

Although this decision was final, the Hattons in our block decided to ignore them, and when the happy block wardens, along with their helpers, starting lining up for the parcels, they were met with a half-ton human blockade.

To our cellblock’s embarrassment, the six Hattons were lying on top of the piles of cartons. The parents, over three hundred pounds apiece, were spread-eagled on the larger stacks, and their four pudgy offspring were straddled on top of smaller ones; they were all chanting, “We want our doo! We want our doo!”

“What the heck’s a doo’?” I asked one of the crew, and he explained they meant “due”, giving it the English pronunciation. Finally, Roger Barton broke through their silly chant, shouting, “Shut up!”

Old man Hatton, purple with rage, and thrashing about like a humongous, bloated fish, screamed, “I won’t shut up! Those parcels are marked American Red Cross, not International Red Cross! Nobody’s getting them except Americans!”

I couldn’t believe my ears. This man and his family, supposed Christian missionaries, would get seven- and-a-half packages apiece, or a total of forty-five cartons, if he had his way!

I didn’t see Rob Connors standing behind me, and was surprised when he said, “Now you know why I can’t stand missionaries.”

Rob had been transferred from a Shanghai camp with his side-kick, Chad Walker, a year or so after we’d been interned. They both strolled into camp with guitars slung over their shoulders and mischief in their eyes, and from the moment they arrived, they regaled us with bawdy, underground songs that had us in stitches. One still comes to mind …

My father was a good missionary,

He saved little girlies from sin;

He could sell you a blonde for a shillin’

Lordy, how the money rolled in!

My brother took care of old women;

My mother made synthetic gin;

My sister made love for a livin’

Lordy, how the money rolled in!

There were lots more verses, and I remember being quite shocked when I first heard them.

The only missionaries I’d ever known were really good people, and I couldn’t see any of them using the Lord’s work to further their own ends. Now, watching the antics of the Hattons, I got to thinking that Rob probably knew a heck of a lot more about the missionary element in China than I did.

Crowds started to converge on the compound when they heard the ruckus, and I saw the anguished faces of the Tucks, Beruldsen’s, and Collishaws, and many other upstanding Christians; I felt sorry for them because of what one family was doing to their image in a camp with a pretty low tolerance for their way of life.

Then the Hattons started screaming again, as a group of internees tried to heft their huge bodies off the piles of parcels. Kicking and screaming, Mr. Hatton shouted, “Don’t you dare touch me, while Mrs. Hatton, flabby arms waving, started to yell, “Leave our kids alone!”, as the children, kicking and screaming, were carried out of the compound.

Barton threw up his hands in disgust and charged into the office, coming out with a bullhorn.

“Listen to me, you two idiots!” he bellowed, “You’re right, these packages are marked American Red Cross, but if it wasn’t for the INTERNATIONAL Red Cross they’d still be sitting on the docks Stateside! There’s no way anyone would get them without the help of the Swiss or the Swedes. How the hell do you think they got here!?!”

A rumble of assent ran through the crowd, as he told the Hattons to get down or they would be hosed down. As he spoke, a huge fire hose was hauled out of the building. I didn’t see a hydrant anywhere, but the threat worked. The Hattons, flustered and fumbling, tried to get down. As they squirmed and slithered, they dislodged the topmost packages, and they came crashing down on them. Everyone just stood and watched, and not a hand was lifted in help. It was as though the coveted comfort parcels had come alive, playing a role none of us would have dared, flipping and bouncing and clobbering their monstrous human targets till there wasn’t an inch of them that wasn’t black and blue.

After the Hattons staggered out of the compound and the hubbub died down, the packages were distributed to all the block wardens and their happy band of helpers.

I couldn’t believe what they contained!

There was instant coffee, something we’d never seen before. Real tea in tea bags; cans of butter that didn’t need refrigeration; crackers; concentrated chocolate bars; cookies; sugar; scrambled egg mix; Spam; soap; toilet paper...and toothpaste! And, now and then, a mash note from some sweet soul who had packed the box. We called it the “fortune cookie touch”, comparing handwriting and messages, soon forgetting the Hattons and their rotten behavior. The simple excitement of sharing and trading, knowing that people in the great world beyond the walls remembered us, and cared, was an emotion so great, it swept all the previous pettiness before it, and helped make my eighteenth birthday the most memorable one in camp!

[further reading] ...copy/paste this URL into your Internet browser:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/MushroomYears/Masters(pages).pdf

#