- by Ron Bridge

Chapter 7

[excerpts] ...

...

Filling my stomach was probably the most important event in each and every day. I was young and growing and always hungry. I had been spoiled in Tianjin, we had employed a cook, and he was good. I relished his speciality, which was to make a duck and two-chicken roast, although a pheasant often replaced the second chicken in the winter. He used to bone them whole and put one inside another and then use stuffing to put them into shape, so that then when it came to carving a knife would glide through the lot.

Filling my stomach was probably the most important event in each and every day. I was young and growing and always hungry. I had been spoiled in Tianjin, we had employed a cook, and he was good. I relished his speciality, which was to make a duck and two-chicken roast, although a pheasant often replaced the second chicken in the winter. He used to bone them whole and put one inside another and then use stuffing to put them into shape, so that then when it came to carving a knife would glide through the lot.

[excerpts]

... Weihsien:

In the first weeks I remember little of our precise diet, except that we ate a lot of bread produced by Qingdao Bakery, and not a lot else.

This arrangement could only last for a few months, after which the inmates would be on their own. A Greek baker, Mr Stephanides from Qingdao, had brought in some yeast and was appointed camp baker, and I suppose he was multiplying the yeast. All food had to be made by the inmates themselves, but since the adults had all employed cooks pre-war they did not even have latent skills on which to call. The bread was rather lead-like at first, but soon the bakers got accustomed to the quantities to use, and the fact that yeast needed sugar to rise properly was `discovered’, not that much sugar was ever available.

The task was fairly formidable: 400 loaves a day were needed to feed 2,000 people.

As food was precious, as much as possible was done to minimise waste. Thus any stale bread was boiled up as porridge for the next breakfast.

The experience has left me with a lifelong dislike for bread sauce. We did have flour, which was so different from other Japanese camps in Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore, where the staple was rice and with it vitamin B deficiency for the consumers. The flour supplied slowly deteriorated as the years passed, until by the end it was mostly weevils’ bodies — protein I suppose — and millet seeds that were milled, but which in their natural state looked remarkably like the seeds that one buys in bags to feed wild birds today.

My mother brought all our rations back from the kitchen to our room and we always ate there at a folding games table that came in our luggage.

She did not want us to eat in the crowded dining room, and most other families with children under five did the same. The queues for serving and eating would have been impossible otherwise, and bawling two-year-olds would have added nothing but irritation to the atmosphere.

The camp had a policy at the kitchens that, if you ate in the dining room, you could ask for a second helping, not always forthcoming, but over the months `Seconds’ became almost universally used as a description for more. Manuel Sotolongo, an eight-year-old Cuban, caused a big laugh when he asked for seconds of salt, pepper and mustard.

I knew very little about the workings of the kitchens, as children were prohibited to go in them. I did take a peek a few times. They were hot, with open fires, with a decking over in which up to five large `woks’ or `Kongs’ were set. These were about five feet across (11/2 metres) with a wooden lid, used to boil water and make stew. (Recipe: water, lots of vegetables and an occasional cube of meat.) Often one of the men had to balance precariously over the lid to retrieve something and it was also not unknown for the lid to collapse and the volunteer cook then got scalded legs.

The cooks did make tempting smells with their soups and stews.

Sadly, lack of supplies meant second helpings were few and one had to be satisfied with the aroma.

These thin stews were generally our daily fare for at least one meal. I did not think too much of them: the meat, if you could find it, was stringy, the vegetables overcooked, even if they were often soya beans or soya bean leaves, and almost a mush. I also missed having any milk to drink. The alternative was water, and even that was a problem as the shallow wells were only five metres from the cesspits.

Mum felt that water should be boiled — definitely a desirable policy — but most of the time there was no fuel, so that was but seldom implemented.

There were three cows grazing in the graveyard in the Japanese area of camp. Pathetic beasts, which were milked for the babies and the hospital patients. Roger had a cupful on most days; I eyed it once and it had been so watered down that the milk took on a bluish tinge. I decided I was not missing very much.

Mum said that we had not brought in much in the way of food, although this puzzled me as Roger’s Pedigree pram had been overloaded with the stuff. I think really Mum was of the opinion that it was better to use currently issued supplies and keep the tins `in case’, for the future.

Thus, like a lot of families, my parents patronised the small canteen provided by the Japanese to buy extras. The canteen was staffed by inmates, supplying, when they had such goods, cigarettes, toilet paper and sometimes small quantities of soap, peanut oil, dried fruit and spices. But we had to have ration cards for these sorts of items and the card had to be marked.

They were paid for by money that inmates were given, called `comfort money’. It was supplied by the British Government to the Swiss, whose Consul in Qingdao, Mr Eggers, used to make a monthly visit starting with a suitcase full of Chinese dollars. I never had much to do with money and the lack of it made little difference to me, in any case the management of any money was in the hands of my mother.

But I did notice that Mum’s small trinkets seemed to disappear from time to time. I learned these financed extra food like eggs for us from the black market.

Anyone who was around ten years old knew that a big trade was happening over the wall, mainly in food, though nobody ever said anything.

Watching and sometimes getting involved, even if inadvertently, was fascinating. The main organiser of the black market was an Australian Cistercian Monk, Fr Patrick Scanlan, using priests to make the transactions. There was a general curfew at lights out, 10 p.m., but in the summer evenings it was not unusual for us boys to sneak out of bed and see what was going on, usually as a sort of dare.

We soon spotted the priests trading over the walls, but nobody ever betrayed them, even to our parents, although I knew from Mum that she was grateful for those extras, even though she was not sure precisely how it was done. Order placed one night, eggs or whatever received the next.

But rapidly the guards realised what was going on and more devious methods had to be introduced, especially when they started cocking their rifles and firing the odd shot in the air. The standard of trust was sufficiently low that it was jewellery, or money, up front.

Fr Scanlan, realising that inmates were free to practice their religion, instigated a system whereby the priests would walk around the hospital area holding their breviaries, but also bearing a basket, hung on a belt under their soutanes. The basket started out being filled with money and sometimes jewellery; towards the end, after the transactions, it now contained the food of various sorts that was on order. One of the older priests had difficulty walking, and had asked his Bishop if he could say his office seated against the wall, and we boys often used to sit by the wall with him idly talking. I was doing that one evening with Brian just after supper. Two guards approached the priest, speaking broken English, and said that there was no way he could read in that light.

The priest said, `I have very good eyes I can read clearly,’ I suspected that the guards had thought the breviary was a diversion. So they then said `Then read to us.’

The priest then started `Pater poster, qui es in caelis Sanctifîcetur nomen tuum...’ I had difficulty stopping from bursting out laughing, because it was obvious the light was too bad to read and the recitation was from memory. But it satisfied the guards and they left. Brian and I then said goodnight and we both got up off the ground to leave, but the priest said, `Boys, would you mind taking these to Fr Scanlan,’ producing two boxes of eggs from under his soutane!

One evening in July Dad came in from his job as a stoker in Kitchen No. 2 to relax before our last meal of the day. `The Trappist, Fr Scanlan, who smuggles over the wall has been caught by the Japs,’ he told Mum.

`How did that happen?’ she asked, obviously shocked.

`What will happen to him now?’

Dad shrugged his shoulders.

`The Japs are going to try him, so it seems.’

The whole camp was aware of the coming trial and it wasn’t just his fellow clergy who were praying that the Japanese would not decide to make an example of the monk. I did not consider it myself, but Mum admitted that many of the adults were afraid he would be executed. He was tried by the Japanese Consular Police, and the only internee allowed at the proceedings was Ted McClaren, the `head’ of the internees. Thesentence was one month in solitary confinement.

I heard some adults saying that was a fitting penance for an Australian Trappist monk.

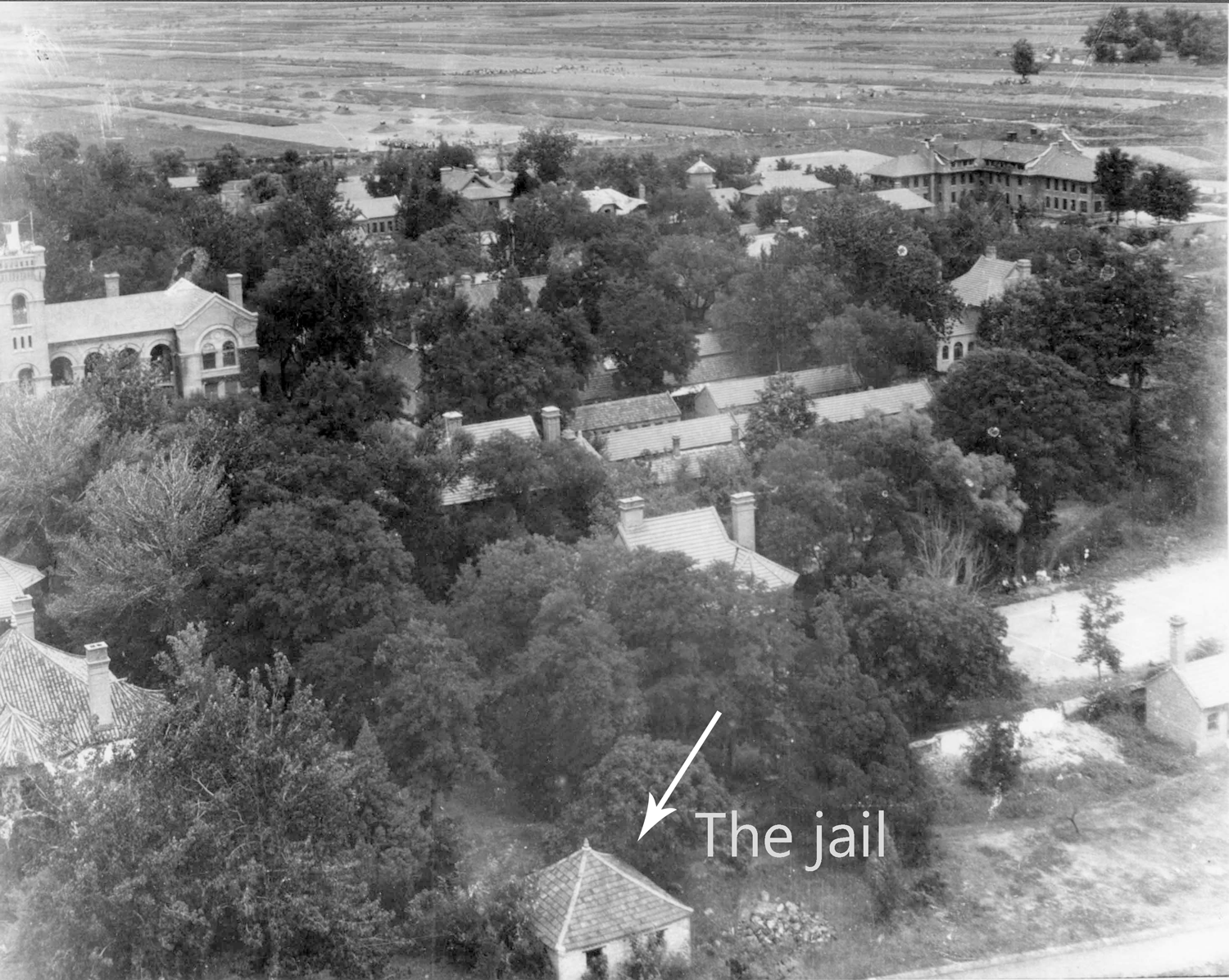

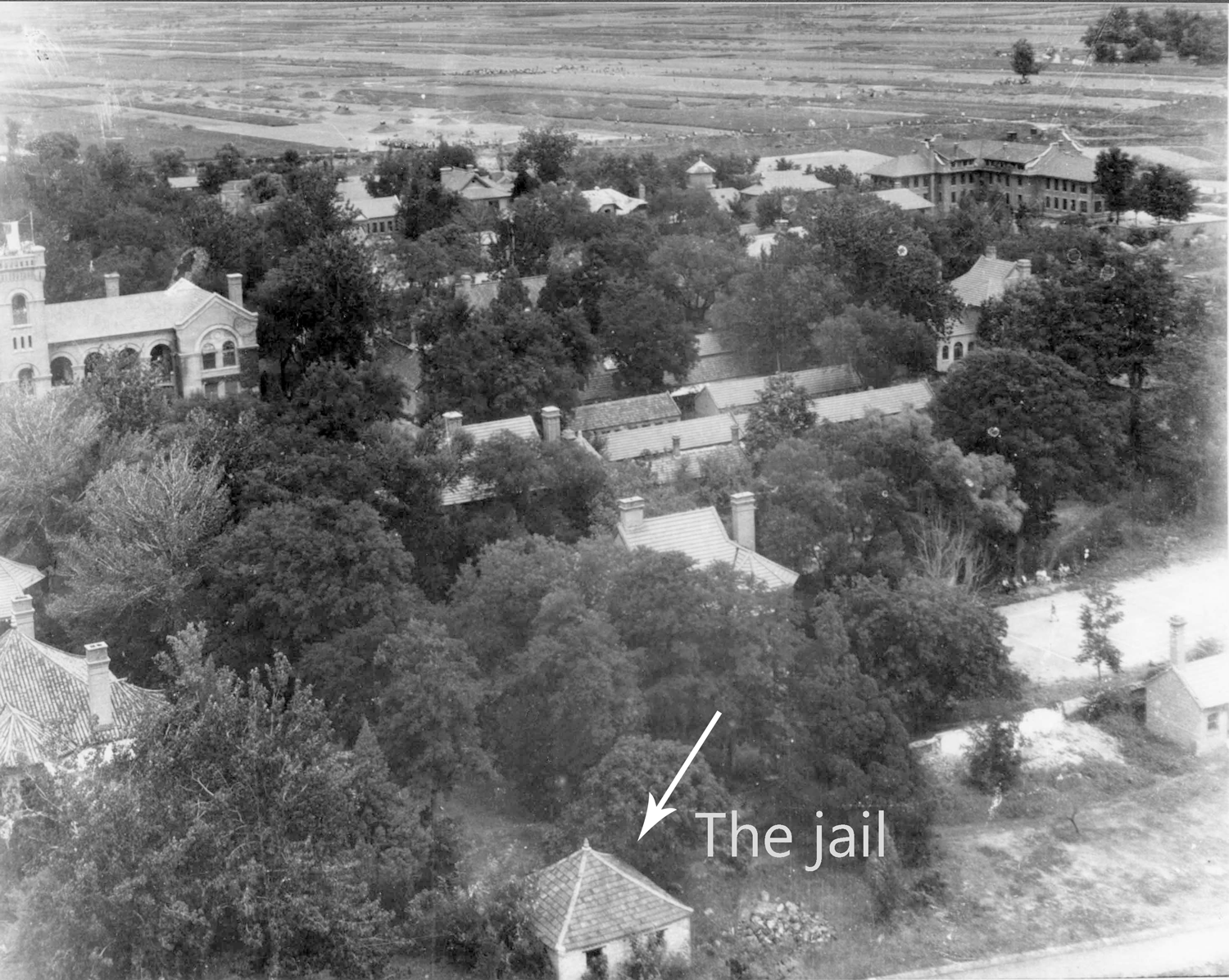

Then the Japanese had a problem. ‘The Commandant’s House was the northernmost of the old missionary houses and the nearest to the internee section of the camp. The only cell was on the ground level of his house. Because of the construction of the houses, the top two floors were living accommodation, whereas the ground level was rather like a cellar and used as such. Fr Scanlan was duly placed in the cell and allowed his breviary. But then Fr Scanlan hit back: he had a fine voice, and used it to sing the `office’ in plainsong.

Fr Scanlan’s fellow priests got as near as they could in a narrow path between two walls and either responded to Fr Scanlan’s chanting or all recited the office out loud. The Japanese listened appreciatively, although the latter was unintelligible to them. They were still relatively relaxed when the midnight office was sung, but come 3 a.m. they were woken up and were displeased. This procedure lasted for a few days.

After a week Fr Scanlan was escorted in front of the Commandant again, in the presence of Ted McClaren, to be told that for good behaviour he was being released. Face-saving by the Japanese, as they would not of course admit that it was Fr Scanlan’s voice at 3 a.m. that had driven them crazy, and they had to put a stop to it somehow.

Peanuts came over the wall in great quantity, and peanut butter became a staple to be put on bread. Ordinary mincing machines were modified by replacing the single cutter and fitting a pair which ground the peanuts into a paste. The rather tedious task of winding the mincing machine on the table usually fell to me. I did this chore for our immediate family and for others in Block 42, always ensuring they got the same amount of peanuts back.

The priests really impressed me in Weihsien; they had become the unofficial morale leaders. Many had long black beards, which I guessed were why my parents had called them `Daddy Whiskers’ in the past. I had occasionally been taken to All Saints Anglican Church in Tianjin, the Church my parents were married in, and they did not go too often in Weihsien. Mum always used Roger as an excuse, saying that he would probably bawl and disturb the service. Dad was into `bells and smells’, I think from his time at Abbotsholme. I was not bound to go regularly, but I found solace in going to sit on the wall near the Church during Roman Catholic Mass and listening to the chanting of plainsong. It was an experience I always enjoyed, although I could not read a note of music at the time. I liked classical music but I think that I inherited my tone-deaf voice from Mum. In fact, I am sure, because Dad could and often did play the piano in Tianjin.

[excerpts] ...

Winter was not far away. Most of the huts had no heating and those with experience of the climate estimated that the temperature could fall as low as 0°F, or minus 17°C. The Japanese promised coal, thus each room needed a stove (the dormitory rooms already had pot-bellied iron stoves, fitted with chimneys made out of four-inch (10cm) tin tubing). The coal duly arrived: a couple of buckets of black powder with the odd walnut-sized lump. One could not burn it in the open and there were no hearths. So, from the engineers came a rapid design for those hut rooms without stoves. They were to build new ones: three foot long, built from bricks obtained from those demolished walls which had once defined each courtyard between the blocks. The stove included an oven, made from a square five-gallon oil tin, and a chimney built out of 3/4-pint soup tins carefully pushed into each other. There was no solder, so the engineers stressed the need to ensure that the top of each tin went snugly into the one before, so that smoke could not leak into the room. Leakage of carbon monoxide, which came from incomplete burning of fuel, was potentially fatal: it could kill the occupants as they slept.

The ovens meant that housewives could cook a little extra, if they could find ingredients. They certainly could keep food hot after collecting it from the kitchen. Often though, there was so little of the food that at any temperature it tasted great. The trouble with the `private’ stoves was fuel, and I recall seeing Mr Nathan, who was Chief General Manager of the Kailan Mining Administration, a man regarded with great respect and who was at least ten years older than Dad, atop the ash pile outside of No. 1 Kitchen. He was carrying a little bucket with him, and had climbed up there in order to pick up, very carefully, small pieces of partially burnt coal to take to his dormitory to burn in their stove. It seemed so ironic: here was a businessman used to dealing with thousands of tons of coal being forced by a war to try to find, with his bare hands, a couple of pounds for his own use.

The Japanese realised that all this illegal building of stoves was going on, and issued smaller cast iron stoves but without the chimney piping. And policy caught up with the facts: you needed to have been issued a stove to be allowed to draw coal, so Dad got two, one for each room. He then had a brilliant idea when he saw the unscrewed top of the pot-bellied stove — he promptly mounted it on the bricks so that there was now a `ring’ to heat kettles and saucepans, and the oven for the `brick’ stove.

Dad said, `I have already scrounged a five- gallon oil tin, and I must now find enough soup, fruit or vegetable tins to make the chimney. I have staked a claim for a number of bricks from one of the end walls. I have also got a small bag of that cement you were playing with ages ago, Ronald, which when mixed with mud should do to cement the bricks together and seal the top.’

When challenged, I agreed that I had a number of iron bars that would make a grate, again trophies from the fire and ash pile from what seemed months before. `I told you Mum, that they would come in useful.’ Mum had to agree that one could ever tell when things would find a purpose. That was the first and only agreement that I ever had from Mum regarding my trait of squirreling things away in case’ they might be wanted. I had pointed out to her that she herself was keeping all those tins of food that had been so elaborately brought in Roger’s pram for a `rainy day’.

[further reading] ...

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/NoSoapLessSchool/book(pages)WEB.pdf

#