- by Edward S. Galt

[excerpts] ...

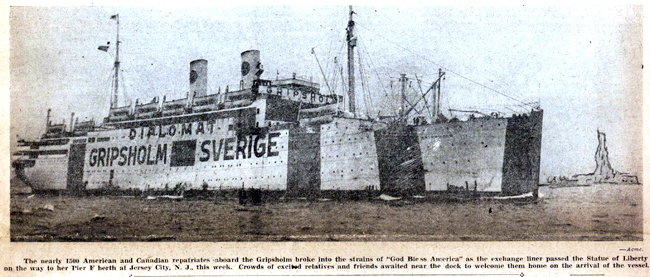

... all the prisoners selected for the return to America on board the Swedish m/v Gripsholm were shortly to be replaced by the ±300 students and teachers of the Chefoo School ...

What follows is an excerpt of a confidential report written by Howard S. Galt upon arrival in the States.

...

fter the camp residents had all arrived, and provisions had been made for living quarters and eating arrangements, it was time for the permanent organization of camp life and activities. We had been informed in advance that the camp must be self-operating as far as labor was concerned – that no servants or workmen would be supplied to us, and that the work must thereafter all be done by ourselves. But organization included much besides labor activities. Recreational, cultural, educational, musical, religious, and other activities and interests were all promoted and regulated by the general organization.

fter the camp residents had all arrived, and provisions had been made for living quarters and eating arrangements, it was time for the permanent organization of camp life and activities. We had been informed in advance that the camp must be self-operating as far as labor was concerned – that no servants or workmen would be supplied to us, and that the work must thereafter all be done by ourselves. But organization included much besides labor activities. Recreational, cultural, educational, musical, religious, and other activities and interests were all promoted and regulated by the general organization.

The main fields of organization were determined in advance by the Japanese commandant, the supreme authority in the camp.

The main fields of organization were determined in advance by the Japanese commandant, the supreme authority in the camp.

According to his plan there were a number of committees to serve the whole of camp life, with Japanese as the chairmen. These chairmen were merely nominal heads who might exert a certain amount of directional and veto power.

On each committee there were three to five members from the camp personnel, usually chosen to represent more or less equitably the three kitchen groups, and one of whom served as the real working chairman. These committees will be mentioned in order. (Factual details may not be entirely accurate as I must now depend entirely on memory. The manuscript of an exact account of the camp, with many notes and statistical material, was taken from my luggage by Japanese examiners.)

The General Committee

A small but important committee, taking charge of general affairs, as the name indicates. Its duties were in part residual – taking charge of many matters as they arose, matters which did not logically belong to the more specialized committees.

The Quarters Committee

In charge of housing, assignment of rooms, etc. Changes in the original housing arrangements and assignment of place to occasional newly arrived members were the functions of this committee.

The Employment Committee

In charge of the permanent and periodic assignment of work jobs. The scope and importance of this committee’s functions will be readily understood. Its decisions and appointments affected the daily work of more than 1,000 people - all of the adults and many of the older children.

Of course there was much labor connected with the commissariats of all three kitchen groups. Accordingly there were three subcommittees to take charge of these divisional assignments. Taking the Peking (Kitchen 3) group as an example: The committee instituted an inquiry of all concerned to discuss the qualifications, aptitudes, skills, and preferences with respect to the great variety of tasks to be done. In the assignments special skills, aptitudes and choices were considered as far as possible. Some skills and aptitudes – for example those of amateur carpenters – suggested permanent assignments to jobs.

In types of work perhaps not requiring much skill, or which were particularly hard and unpleasant, frequent rotation was most satisfactory. The week was chosen as the unit of time and so it came about that there was posted a weekly bulletin giving a complete list of assignments to tasks for the following week.

These weekly lists probably contained the names of at least 100 people. Of kitchen and dining room activities more will be written below.

Besides the work in the three kitchen groups there were general tasks by which the whole camp was served. There was the central bakery, which operated more than half of the 24 hours of each day, thus requiring several shifts of workers. There were the pumps which supplied water to the reservoir tanks, and which had to be manned steadily all day long. There were the furnaces and boilers for the supply of hot water for the bath showers and for washing purposes, and distilled water for drinking. These required men with engineering experience. There were the sanitary installations to be cared for – work the more necessary and the more unpleasant because of the defects of the plumbing system.

There were jobs for carpenters, blacksmiths, plumbers, metal-workers, masons, and electricians. To these jobs there were usually permanent assignments as mentioned above.

The Supplies Committee

This central committee consisted of two divisions: one in charge of general supplies, and one in charge of hospital supplies. As to general supplies, chiefly food and fuel, for the first few months the operations were carried on in part by three sub-committees for the three kitchens. Later there was a large degree of unification and one general committee received supplies daily from the Japanese in charge, weighed or counted the total and made an equitable assignment to the three kitchens. Supplies were usually brought into the compound on Chinese carts and wheel- barrows, with Chinese drivers or runners in charge. But after two months or so, the Japanese authorities, becoming suspicious of secret communications with the outside world through the carters, ordered that Chinese bringing the supplies were not to enter the compound gate. From that time it became necessary for supplies committeemen to meet the vehicles at the gate and drive (or lead) the cart mules, or push the wheel-barrows, to the supplies depot several hundred yards distant near the south border. For the men concerned, and for spectators, these were new and interesting experiences. The Chinese mule has his own ideas about the language and methods of the driver and the mule’s responses to a stranger are not always cordial. As to the wheel-barrow, the usual type is large and carries its load high, and an amateur’s efforts to balance the load are not always successful. But on the whole the committeemen did well. There was no stoppage in the general stream of supplies and only one or two run-aways by the mules.

The tasks of the division in charge of medical supplies were quite different. After the initial opening of the hospital, orders for supplies for the most part had to be placed in Tientsin or Tsingtao in care of the Swiss Consuls. When these arrived they had to be carefully conveyed to the hospital and distributed for use or placed in the pharmacy.

The Finance Committee

The operations of this committee were much like those of a bank. During the first few days in camp all members were compelled to hand in to the bank their ready cash. To each person was issued a statement of account, corresponding to a bank pass- book. Subsequently, according to the regulations of the Japanese authorities, the bank would pay monthly to each depositor a fixed sum (at first $50 North Chinese currency – abbreviation “F.R.B.” for “Federal Reserve Bank” – later increased to $100) for use in the camp. Such funds were needed to make purchases in the canteen, pay minor assessments to the kitchens for “extras” or to pay laundry bills.

Later when “comfort money” from the American and British governments was receivable, the specified amounts were credited to the individuals’ deposit accounts, and part payments were added to the banks regular monthly payments.

When those camp members whose names were on the repatriation list were ready to leave, the bank arranged for the transfer of the specified amounts (not to exceed F.R.B. $1,000 per individual) to Shanghai for use on the voyage. Provision was also made for the issue of smaller sums for use on the journey by rail to Shanghai.

Among camp members there were a number of competent and experienced bankers from the North China cities, and with their appointment to the Finance Committee, it goes without saying that the banking operations were well managed. It should be added that the actual cash was kept in custody by the Japanese, and the Japanese accountants “chop” (seal) was necessary for all cash transactions.

The Discipline Committee

The Camp was at all times under the ultimate control of the Japanese consular police and of the guards appointed by them – all under the supreme control of the Commandant. But the ordinary conduct of camp members – social or anti-social as the case might be – was under the control of the Discipline Committee. An active member of this committee was Mr. Lawless, an Englishmen whose regular position was head of the Legation Quarter police force in Peking. Mr. Lawless was a large, portly, impressive-looking man, usually very jovial, but at times very stern, admirably adapted to his task. This task was on the whole not very difficult, for the behavior of camp members was good, with few exceptions.

Perhaps the most difficult part in this committee’s administration had to do with the control of the so-called “Black Market” conducted “over the wall” between camp members and Chinese who were bold enough to approach the wall from outside. At this point it may be explained that some time during the months preceding the establishment of our camp the Japanese military had occupied and fortified the compound. Guard towers of brick had been built at all corners and strategic points, and against the compound wall in the inside, at intervals of 30 or 40 yards, mounds of earth had been thrown up of sufficient height to enable guards to stand watch or shout over the wall. Some of the fortifications had been demolished prior to our occupation of the camp. It will be easily understood that the lower port holes in the corner towers, and the numerous mounds inside the wall could easily facilitate communications with people outside.

The chief market demand of camp members was food stuffs – especially eggs, and honey, sugar and other sweet products – to supplement the meager dining room fare. Tobacco and matches were also much in demand.

All such traffic with people outside was forbidden by Japanese regulations, but the Japanese guard was insufficient to prevent such traffic – especially at night. The Japanese authorities expected the Discipline Committee to cooperate in the enforcement of these regulations. But the Discipline Committee was half-hearted and rather indifferent in the matter. Contact with the outside world seemed hardly within the responsibility of the committee. Furthermore a large element of public opinion in the camp heavily favored these “Black Market” operations – partly on the ground that the authorities were not keeping the promises made in advance regarding the camp diet. With such conditions the Discipline Committee did not take much part in enforcing Japanese regulations relating to this traffic and these “over the wall” operations continued during the whole period – at least to the date of the repatriation of Americans (September 14). At times there were even suspicions that some of the Japanese guards were making “squeeze” money in these operations, and were not too energetic in enforcing regulations.

Besides the above-mentioned committees there were other committees of an un-official character – un-official yet making large contributions to camp life. A few of these will be considered.

The Education Committee

There were a considerable number of school-age children in camp. For most of these, provision was made in two school groups. Peking had a large and well organized “Peking American School.” There were in camp a few teachers and perhaps 20 or 30 pupils from that school. Places in the church or church yard for classes were found, school desks were assembled from corners of the compound and before many days the relocated but attenuated “P.A.S.” was again in operation. Studies were carried on so successfully that the committee in charge felt justified in authorizing a “commencement” with official graduation of 3 or 4 members of the senior class. This graduation ceremony, prepared for and conducted in the approved and conventional American style, was a highly interesting event in the camp, with an audience which entirely filled the church.

In the British tradition there was the Tientsin Grammar School. In the camp were a few of the teachers and some of the pupils from that institution. They also were organized into a school and in quite a regular way were able to carry on their studies.

In addition to these schools, there was a large and well conducted kindergarten and also some educational classes for young children conducted by Catholic sisters.

Besides these formal schools there were organized many classes, lectures and discussion groups in the field of adult education. The curriculum subjects probably numbered as many as 20 or 30, studies in the various languages predominating, and among the languages Chinese most in demand.1 Besides the lectures offered in series to select groups there were general lectures, usually one each week, on themes of common or popular interest.

The Entertainment Committee

After the beginning of camp life, not many weeks elapsed before a series of weekly entertainments was provided. These took many forms, dramatics and music programs being the most frequent. Members of the group coming from Peking – a city always proud of its cultural attainments – were most resourceful in preparing entertainment programs, but the Tientsin group was by no means backward. In many of the entertainments, both dramatic and musical, all three of the city centers furnished talent.

In this connection it is not improper to mention Mr. Curtis Grimes, a young pianist and conductor with a rapidly growing reputation in Peking. His most notable contributions were his own piano concerts, and the leadership of a chorus and an orchestra.

The nucleus of both chorus and orchestra had been trained for longer or shorter periods by Mr. Grimes in Peking. These members were re-enforced by excellent musicians from the other cities.

1 The Chinese language instructor was George D. Wilder, a retired missionary who had returned to Peking to teach in the College of Chinese Studies.

Among the musical programs of the chorus were three of the great classical oratorios.

In this connection it may be noted that, at the time of the establishment of the camp the Japanese authorities were good enough to give special permission to transport to the camp a grand piano from Peking. Later a second piano was similarly brought from Tientsin.

The church serving as auditorium with a seating capacity of 700 or 800, made possible the regular entertainment programs. It was soon noted that if programs could be given twice, the attendance of practically the whole adult membership of the camp was possible. Friday and Saturday evenings were usually chosen for the two settings, and on Thursday tickets for the two evenings in equal numbers were freely distributed.

Besides the evening entertainment there was an almost daily series of athletic sports. The grounds near the hospital, already mentioned, were used for tennis, basketball, and volleyball. An athletic field left of the church was larger and there baseball and hockey were played. By far the most popular sport was baseball – most popular both for the players and spectators. The size of the grounds cramped the game somewhat so that the soft- ball (or playground ball) was commonly used. For this also the grounds were really too small, so that some special “ground-rules” were necessary, one of the most important being that when the batter knocked the ball over the compound wall he was entitled to a “home-run.” In the selection and matching of teams all of the major divisions of camp personnel were recognized. Each kitchen group had its team, and at times a second team as well as a first. Each of the three cities – Peking, Tientsin, and Tsingtao – had its team. Some of the larger corporations, such as the B.AT. (British American Tobacco Co.) and the Kailan Mining Administration, had their teams. Other teams were selected quite miscellaneously by captains, appointed or self-chosen. There were boys’ teams and girls’ teams. But the team which, after many contests, proved superior to all was a team selected from among the Catholic Fathers. The whole camp was surprised at the proficiency of this team and at the interest both Catholic priests and nuns manifested in the game. One of the Catholic bishops took part in the game. The best player in the whole game was a priest whose nickname was “Father Wendy.” Although competition was keen there was the utmost harmony and good feeling. When the weather was good there were games almost every evening and spectators gathered in crowds. At some of the keenly contested games probably more than half of the entire camp (often including some of the Japanese guards) was present along the sidelines.

Among entertainments there should be mentioned one organized not by the entertainment committee but by the Catholic Fathers. It was an out-door performance held Sunday evenings.

Its leading spirit was a Dutch priest of great vigor and vitality, a good musician and possessing marked natural qualities of leadership. English was the language which was most used, of course, but the Father in charge had very incomplete knowledge of English, and his foreign accent, and the mistakes which he made, which did not at all quell his enthusiasm, were part of the entertainment. The program, largely improvised and prepared for each occasion, included much music, instrumental and vocal, the latter in the form of community singing. The words of the songs, usually adapted to familiar melodies, often referred to interesting camp happenings, or made “local hits.” Besides music, with a continual flow of interactions and humorous comments by the leader, there were simple dramatics, puppet shows and shadow pictures. A small movable stage, with suitable electric lighting, was set up for each occasion. These entertainments seemed to fill a Sunday evening vacancy in camp life and became very popular with an attendance of people, both sitting and standing, of 500 or 600. It may be added that the Protestant church held Sunday evening song services, but they were by no means as popular as this entertainment by the Catholics.

A very different form of entertainment, the game of chess, while not under the auspices of the Entertainment Committee, was quite popular, promoted and organized by a chess society. The players were classified and a systematic tournament was held.

The Medical Affairs Committee

The operation of the hospital and the general medical and sanitary care of the camp were the functions of this committee. There were a considerable number of doctors in the camp, among them a chief surgeon and a prominent physician from the Peking University Medical College. Although there was quite a little illness in camp and the resources of the Hospital were fully used, there was no serious epidemic and on the whole health conditions were quite good. One of the senior physicians was a competent and experienced oculist, and there was present a competent and experienced dentist. Offices for them were provided at the Hospital and thus the corresponding special needs of camp residents were cared for.

As to general sanitation the deficiencies in the sanitary installations of the Japanese were the cause of extra difficulties, dangers, and unpleasant tasks, but with careful safe-guarding, and general cooperation, the dangers were overcome.

Committee on Engineering and Repairs

This committee was under the direction of a trained engineer. In cooperation with the employment committee there were organized squads of masons, electricians, plumbers, metal-workers and carpenters. Some of the work of these specialists consisted of repairs, but much of it was of the nature of remodeling or rebuilding to remedy deficiencies in the original preparation of the camp. Some of the men among these skilled workers were men of special training in these vocations, but most of them were men whose avocations had attracted them into these fields and whose skills were those of amateurs.

In the fields of women’s work there was some unofficial but very effective organization. A few sewing machines were available and so a center for sewing and repair of clothing was established. Repairs of course implied chiefly hard work, and this was distributed among a large number of women to be done in their homes.

As to laundry work, most people did their own, often in the midst of great difficulties and limitations. Washing was of course a necessity but many came to the conclusion that ironing was an unnecessary (or unobtainable) luxury. In the laundry work many women helped their men friends in voluntary and informal ways. However, a group of Catholic Sisters, taking advantage of facilities in the Hospital basement, organized a semi-public laundry, and eventually arrangements were made by them with skilled Chinese in a village outside to do laundry work on a commercial basis.

One enterprising woman widely known and experienced in the management of a shop in Peking, took the initiative in establishing camp exchange (known as the “White Elephant Exchange”) where, besides some buying and selling, people could exchange their own useless things for things useless to other people – a process of transformation which rendered all things useful. This institution was not fully organized for several months, but when it was installed in its own quarters and clearly advertised, it rendered much service to the community.

Other aspects of women’s work will be described below in connection with kitchen and dining room service.

There were three other forms of community service not mentioned in what we have reported about organization and employment. A barber shop was manifestly a great need and, when two men with the necessary skills were found, a room was provided and the shop opened. Shoe repairing was a second need soon widely felt, since the foot wear was deteriorating with the heavy work and a shoe-repair shop was opened. A third need was watch repairing. Several decades earlier the Catholics gained the reputation of introducing the arts of watch and clock repairing into China, so it was not surprising to find among our Catholic Fathers a man with skill in this art – whereupon a shop for his services was duly opened.

Thus, sooner or later, as almost all the practical needs of a community of 2,000 people became evident, ways of supplying these needs were found and adopted, so it might almost be said that our camp was a self-contained community.

[excerpts] ...

[further reading] ...

copy/paste this URL into your Inernet browser:

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/DonMenzi/ScrapBook/1943-Galt_Weihsien-1.pdf

#