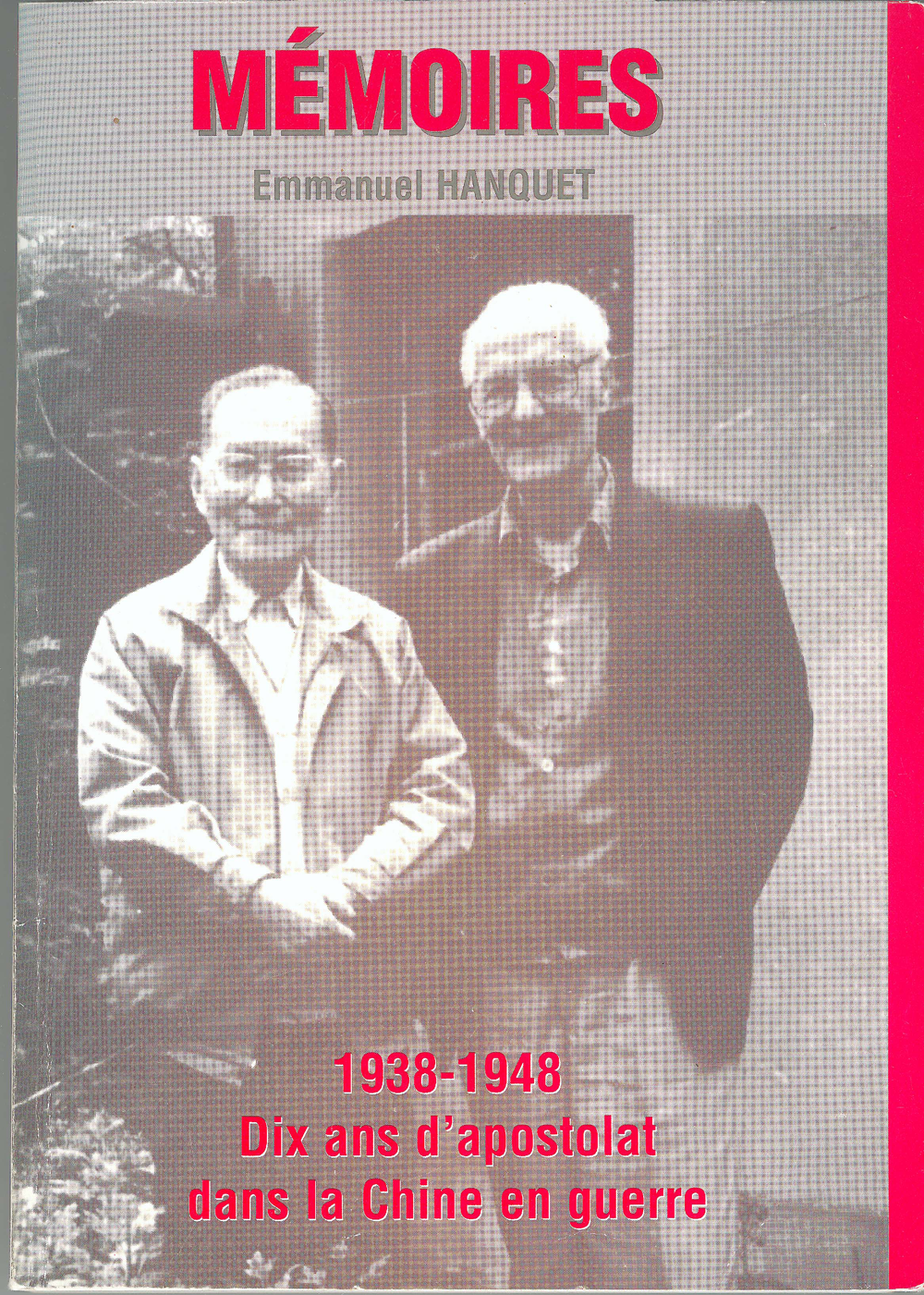

- by Emmanuel Hanquet

Tangling with the Japanese

[exerpts] ...

...

On the way there [Weihsien] our train stops for an hour to take on board a contingent of American and British folk who were to find themselves interned with us. I have the happy surprise of finding in the group six other Belgian colleagues from my missionary society, who are likewise made to board by the police. They are Fathers De Jaegher and Unden, who are working in Ankuo diocese; Keymolen and Wenders, who are professors at Suanhua grand seminary; Gilson, who is the Peking procurator; and finally my very good friend Father Palmers who, as I write, is the last survivor of that group of six.[He died three years later while parish priest at Taipei on the island of Taiwan.]

On the way there [Weihsien] our train stops for an hour to take on board a contingent of American and British folk who were to find themselves interned with us. I have the happy surprise of finding in the group six other Belgian colleagues from my missionary society, who are likewise made to board by the police. They are Fathers De Jaegher and Unden, who are working in Ankuo diocese; Keymolen and Wenders, who are professors at Suanhua grand seminary; Gilson, who is the Peking procurator; and finally my very good friend Father Palmers who, as I write, is the last survivor of that group of six.[He died three years later while parish priest at Taipei on the island of Taiwan.]

Weihsien Camp

Two thousand internees share what this camp has to offer. It was formerly a Presbyterian mission set in the heart of Shantung Province. The founder of Time magazine, Henry Luce, was born there into a family of Protestant pastors. Our Japanese gaolers have kept the best buildings for themselves and leave us with the student accommodation and with a number of buildings which had been used for teaching.

The terrain surrounding the camp was gently undulating, not to the point where you were prevented from seeing what was going on beyond the perimeter walls, though in order to see over those walls you had to go up the single tower which dominated the centre of the camp. Going up was, naturally, forbidden.

The little student rooms were built on to one another side by side, twelve to fifteen to a block, and formed a succession of rows which were separated by little narrow gardens that were overgrown when we arrived. Groups of blocks could be divided into three or four zones or quarters, each having a kitchen equipped with a simple outside boiler which provided, two or three times a day, hot water for those who wished to make a cup of tea.

Our little room stood a somewhat apart. At a pinch you could get four people into its 12 square metres, and that was what we had to do. Four colleagues, fortunately, all from the same missionary society, the Society of Mission Auxiliaries. We share our riches and our poverty… Raymond de Jaegher, who had managed to bring in two wooden chests, let me have them for a bed, while my three comrades had salvaged some iron frames that resembled bed bases. Simple deal pedestal tables served as bedside tables… indeed tables for all purposes. To house everything else a collection of odds and ends of wood somehow turned into a rudimentary set of shelves. In times like those, you had to make the best of it! Improvisation and ingenuity reigned.

Luckily, we had none among us who had been convicted of ordinary crimes. We were all deemed to be political prisoners, gathered up and put away because our governments were at war with Japan. Everyone had been living in North China: Peking, Tientsin, Tsingtao or Mongolia. Thirty or so of us Belgians found ourselves in the midst of a host of British and American internees, along with a few Dutch and others. We had become enemies of Japan on the day our own government, exiled in London, decided to open hostilities with Japan to protect the uranium reserves in the Congo which were so coveted by the Americans.

Actually, in March 1943 there were more than a hundred Belgians in the camp. The majority were missionaries working in Mongolia; Scheut Fathers; and Canonesses of Saint Augustine. They left us a few months later, were transferred to Peking and interned there in two convents.

So we ended up as ten or so priests and four nuns available to serve our fellow prisoners. Initially, life in camp involved a lot of feeling one’s way. How should things be organised? Who was going to teach, cook, mend, build, fix up? Everything had to be sorted out.

For example, in No. 1 kitchen where I had volunteered to work our only equipment was six huge cast-iron cauldrons each heated by its own stove. We had to improvise lids using planks and carve great spatulas out of good wood in order to stir the grub as it was cooking ...

Very quickly the senior people from Tientsin, Tsingtao and Peking proposed to our guards that we should be left to organise life inside the camp, while they kept an eye on us and stopped us from running away… For our forty guards, this proposal had to be a good one. They accepted it and concentrated their energies on guarding the gates and controlling the Chinese who came into the camp to provide various services. They also had to mount a night watch on the seven or eight watchtowers which stood on the perimeter of the camp. Later their task was to become even easier as ditches were dug at the foot of the perimeter wall, to which were added strands of electrified barbed wire.

Life slowly settled down. It was not yet a model community, but all bent themselves to the task of giving it a good foundation. Elections were held to establish committees to deal with various aspects of camp activity: committees for discipline, housing, food, schooling, leisure activities, religious activities, work, and health.

At first each committee comprised three or four people. Later, when camp life settled down to its cruising speed, we were to limit each committee to a single elected person. Every six months we replaced or reelected them. The first discipline committee was chaired by the American Lawless who was impressive and good-humoured. His wife was Swiss and she died in camp. Lawless had been chief of police in the British concession in Tientsin and he took on his task in the camp with competence and authority. Later, when there was an exchange of prisoners, he would be repatriated and replaced by an Englishman called MacLaren, who had a family and had been the Tientsin director of a British shipping company.

As for education, we turned to the teachers. Some of them had arrived in camp with their pupils. It proved to be not too difficult to set up two teaching groups, one each for British and American teaching programmes. There were some two hundred children and adolescents running about the camp and it was pretty urgent to arrange plenty for them to do!

Clandestine Scouts

Well, now, one Sunday in springtime Father Palmers and I were sitting on a seat by the central alley. The Protestant service had just finished and we were chatting with some others from the kitchen and the bakery. Cockburn and MacChesney Clark, both old British teachers, were, like us, regretting the lack of educational activity for the young. All four of us were former scouts and ...

[further reading]:

copy/paste this URL intp your Internet browser ...

#