- by Langdon Gilkey

Chapter 2

[excerpts] ...... Camp organization: The Committee ...

The initial meeting of the “leaders,” held that first night we arrived, took place in a large room in the old school building reserved for administrative offices. When Montague and I arrived together, the room was filled with important looking strangers. Most of them seemed to be British businessmen, with some Americans thrown in. There was a scattering of missionaries, and in one corner a small contingent of Catholic priests. Partly by surmise, partly by asking, I found that they were, like ourselves, the temporary

representatives of what were clearly the four main groups of the camp: Tientsin, Tsingtao, the Catholics, and the newly arrived Peking contingents. Probably picked hastily and arbitrarily much the way we were, these men represented the informal leadership that had been established in each city before coming to camp. And as each of them sensed, if anybody was to solve these early problems of the camp, it must be these representatives. Hence immediately they agreed to meet there every night in order to plan an organized attack on our difficulties, and to ask the Japanese rulers of the camp to come in to discuss with them whatever needed to be done.

representatives of what were clearly the four main groups of the camp: Tientsin, Tsingtao, the Catholics, and the newly arrived Peking contingents. Probably picked hastily and arbitrarily much the way we were, these men represented the informal leadership that had been established in each city before coming to camp. And as each of them sensed, if anybody was to solve these early problems of the camp, it must be these representatives. Hence immediately they agreed to meet there every night in order to plan an organized attack on our difficulties, and to ask the Japanese rulers of the camp to come in to discuss with them whatever needed to be done.

My first sight of how men behave in relation to power came in those sessions when our political structure was being born. What became apparent at once to my fascinated gaze was the serious way in which these Titans of North China’s business world began jockeying among themselves for leadership.

With the exception of the priests and a few of us who sat in the back rows, most of those in that large room represented some large European, British, or American business in China fully as much as he did his group in camp. These men were “Stone of Standard Oil,” “Robinson of National City,” “Jameson of British and American Tobacco,” “Campbell of Butterfield and Swire,” “Brewster of Lloyd’s,” “Johns of the Kailon Mining Company,” and so on.

In the course of these early stages, each saw himself and the others in terms of the image created by the power of his company, and by the prestige of his own role in that business. Each brought with him, therefore, not only long habits of personal authority, but the expectation—indeed the need—to exercise the same dominating role here that he enjoyed in the treaty ports. As a professor needs recognition when he delivers a paper, or a minister needs gratitude when he has preached a sermon, so these men needed authority—even if realistically it was the paltry power of an official position among a gang of internees in the hinterland of China.

This struggle for leadership made itself evident in many subtle ways. Ostensibly, when each man spoke in those informal meetings, he was concerned that the problem under discussion— whether sanitation, food, or leaky roofs—be solved, and he would carefully address himself to that problem. But it was evident from his tone of voice, his manner, the emphasis of his speech, and above all from the way he handled the alternative suggestions of others, that he was also anxious that his be the germinating mind that provided the resolution, and that his be the voice that ended the discussion.

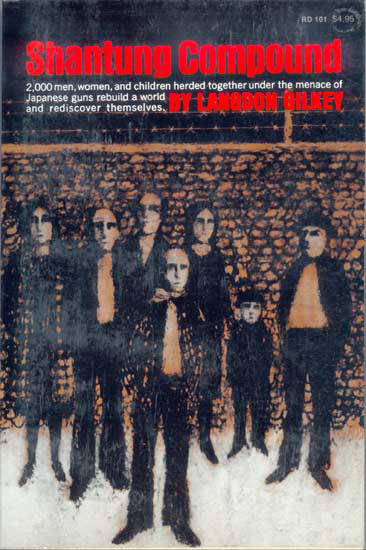

photo: election of the Committee-members

This struggle for the authoritative voice, for the dominance which others not only respect but give way to in will and opinion was both evident and fascinating because prior to these meetings no one had such authority. It all had to be generated right then and there and, so to speak, out of the sole materials of human will and brains. There was no camp chairman, no government, not even a chairman of the meeting; all such posts of authority were still “up for grabs.” Nor were there any of the outward supports and symbols of personal authority: transparent wealth, support of powerful groups and forces—or guns. The only external authority possessed by anyone was that steadily fading aura of the prestige he had once enjoyed in the world outside. Whatever dominance a man achieved in that group, he gained through inherent personal capacity for power. Such capacity is composed of those intangible but basic qualities that cause the outward signs and symbols of authority to gravitate to and remain with a particular man. These qualities are the ability to think quickly and relevantly, the crucial force of great self-confidence and iron firmness of will, and boundless personal energy. The man who had these inherent qualities, like the man with a rapier among those armed only with clubs, could in a short time stand alone over his fellows.

To those of us who watched this developing political struggle, it was soon evident that by the end of the first week these intangibles had done their work; the men with rapiers were already victorious. The character of the discussions had gradually changed. At the beginning any one of the twenty or so men in the room might have felt he could compete on an equal footing with any other man and, if he thought it prudent, challenge the opinion of even the most potent. This was soon no longer the case.

A hierarchy of power had appeared as a few men attained a subtle but real dominance. Now, before committing themselves to an opinion, most of the twenty waited to hear what these few would say; and when these men had made their statements or suggestions, the others would quickly fall into line. At this point, only the great dared challenge the great; the rest had given up the fight. They would rather now be secure on the side of the winner than reach for the glory of power, only to find themselves defeated, isolated, and humiliated. So, without any external force, even without a hint of a ballot, but only by the quiet processes of self-elimination, the list of contenders had been reduced to two or three giants who were still able to contend for the role of Caesar.

In these nightly meetings I also recognized for the first time the unique character and value of the business mind. The core of its strength was what I might call the “mentality of decision.” One or two of these men seated around the table had taken part in academic discussion groups in Peking. There we pondered such abstract issues as peace, international justice, and the relations of ethics or theology to the world of affairs. I had noted then how strangely silent, though observant, polite, and respectful, these men had been. By contrast, we academicians had fairly flowed with verbiage. And as hour after hour went by with no comment from these business types, I thought to myself in some disappointment and not a little disdain, “nice, responsible men, but hardly bright—surely not able to think.”

Here, however, all was different. The minds of these men, accustomed to practical problems, which called for both know-how and decisiveness, clamped onto our situation and dealt with it creatively. What was needed here were concrete answers to technical and organizational problems. Here general principles and ultimate ends—their interrelations and connections with life—could not have been more irrelevant. To be facile in the area of abstractions or of general truths was of no help when the oven walls were cracked, when the yeast wouldn’t raise the bread dough, when slightly smelly meat was delivered in hot weather. Now it was the professional mentality that was proving useless, and the academic voices that were strangely silent. I could see the concrete need only after they had pointed it out to the Japanese; I could recognize the neatness of their solution only after they had explained it to us.

These political and organizational sessions continued for about ten days after our arrival. Then, one evening, a Japanese interrupted our meeting. To everyone’s surprise, he announced that committees to represent the whole camp must be formed within forty-eight hours.

There were, he said, to be nine such committees, and he listed them: General Affairs, Discipline, Labor, Education, Supplies, Quarters, Medicine, Engineering, and Finance.

A Japanese would be in charge of each of these departments of camp life; under him would work one internee who would be the chairman of the committee concerned. The internal governing body of the camp, he continued, was to consist of a council of the nine chairmen of these committees. This council, as a body, would represent the camp to the ruling Japanese authorities. For their own reasons, the Japanese did not wish to have to deal with one powerful man in whom could be embodied the will of the camp. At the time we resented this idea as being against our interests. We wanted a strong leader to represent our needs to the Japanese. But long before the end of our sojourn, most of us agreed that the Japanese had been quite right, although for different reasons. No one among us was big enough for that enormous job.

This Japanese order, abruptly laid down without further discussion, tossed into our laps a ticklish political problem: How could the nine-man council be chosen?

An election by the whole camp was out of the question. In the first place, such a complex matter as a democratic election could never be organized within forty-eight hours. Next, the ordinary voter could not at this point have any idea for whom or for what he was voting. Almost no one was as yet known to more than a few of his intimates; and little about the projected political structure would be understood by anyone outside that room.

It was decided that initially, at least, this ruling committee would be formed by appointment. The method was to be as follows: the present informal leaders of each of the four groups (Peking, Tientsin, Tsingtao, and Catholic) should nominate a slate of nine men from their outfits—one for each of the nine committees. Each sector of the camp would thus be represented on each committee, the several committees to consist of these four men, one from each group. For example, I was the man chosen by the Peking leaders to be on the Quarters Committee, and so I would presumably join the representatives from Tientsin, Tsingtao, and the Catholics. Then, each of these committees would meet together the next evening to choose one from among the four to be chairman, to sit on the council of nine, and to represent the entire camp to the Japanese in all matters under his jurisdiction. This was a roundabout method at best, but it seemed to make sense considering the situation.

The next night we all met to pick our leaders, and a strange sort of session it was. I felt fairly excited, for I knew that if there had been political pulling and hauling, attack and defense, before in our ordinary sessions, it would be doubled now. The political prizes had now been clarified; and they had been increased in number. The result was that many would-be leaders who had given up the fight to be Caesar could now return to the lists in competition for lesser spots on the ruling council.

As the rest of the men arrived in the committee room, I realized that many new faces had been added to the original twenty or so.

Consequently most of us were probably unknown to each other. Then I found myself sent to a corner of the room designated “Quarters,” to which three others had been dispatched, a Britisher from Tsingtao, another from Tientsin, and an American Catholic priest. We eyed one another warily for a moment; then we all laughed sheepishly over the fact that we four strangers were to pick from among ourselves a chairman for the camp Quarters Committee.

The first move was made by the priest. He was a quiet, pale, bland, but quite firm American professor of philosophy. He spoke easily but with precise formality.

“It has been settled authoritatively and finally by our presiding bishop that we of the Catholic clergy are not to take any ruling or leading roles in the camp; rather we are to leave the political direction of things entirely in secular or lay hands. Thus, by order as well as preference, I remove myself at once from competition for this post—although I shall be glad to cooperate with the committee in all matters relevant to the housing of our priests and nuns. Thank you.”

Thus was exorcized the brief but unreal specter of Catholic rule among us.

I was about to make the same sort of statement, pleading youth and inexperience, when the lively looking Britisher from Tientsin began speaking. He had introduced himself as Shields, “Far East Shipping, you know.” He was a handsome man with a small, neat mustache, sprucely dressed for an internee in a tweed jacket and ascot, with matching silk handkerchief in his breast pocket. He had a pleasant, frequent smile and intelligent, alert eyes. But the way in which his remarks seemed to beat one to the gun could signal a lot of ambition—or at least so I thought as I looked at him.

“That seems to me a very wise move on the part of you fathers,” he remarked briskly, “I want you to convey to your bishop for me my personal appreciation for it.”

Fie then turned to me, obviously expecting my similar withdrawal from competition. I did not disappoint him, which left the two Britishers to work it out between themselves. At this, the alert Shields grabbed the ball again, and turning to the other Britisher, he asked, “And what sort of experience have you had in this kind of work? Robbins—did you say your name was?”

The moment I looked carefully at the man from Tsingtao I realized somewhat sadly that this would be no contest. A genial, portly, middle-aged Englishman, comfortable with his pipe and heavy tweeds, with a round, fleshy, kind face and heavy-rimmed glasses, he was obviously no match for the aggressive Shields.

“Yes, my name is Robbins,” he said modestly, “and I’m just an engineer from Tsingtao. I can’t say I’ve had too much experience in housing people—for that has never been my line. I certainly don’t want to shirk and will be glad to cooperate with any chap, but actually I can’t lay claim to any particular qualifications for this job, you know.”

We all turned back to Shields, expecting out of deference for the formalities, if nothing else, much the same modest disclaimer —at least in the first round.

Things had developed so well for him, however, that Shields was not interested in form; he struck while we were all off balance.

“As a matter of fact, chaps,” he said, “I happen to have had a good deal of firsthand experience in Tientsin—head of quarters there, you know—and so I’m not altogether ignorant of the sort of problems we’ll run into. Actually, in my business I’ve had to deal quite often with top Japanese, invaluable experience for this sort of job, you know. Also I do speak rather passable Chinese. [Later I found even I could speak the language better than he.] Therefore chaps, since none of you seems to feel like doing this, I suggest that I be appointed, shall we say, temporary chairman. Then when we all get to know one another better, we can choose a permanent one.”

We were hardly in a position, since we had all backed out of the door, to prevent his locking it from the inside. So we weakly assented to his proposal, and presto—our chairman had been chosen!

This small political gust over the chairmanship of the Quarters Committee increased into gale force among the four nominees for the General Affairs Committee, considered by all to be the central directing agency of camp life. Ever since we had arrived, the question “Who will run the camp?” had been bruited back and forth by politically minded internees. All the serious candidates for local Caesar had been nominated for the General Affairs Committee: Montague, the British American Tobacco man from Peking; the reigning bishop of the Catholics; Harrison, the leading importer from Tsingtao; and finally Chesterton from Tientsin, the solemn British chairman of the massive Kailon Mining Company. Already everyone knew the real battle would be between Montague and Chesterton, representing as they did the significant social and commercial forces in camp life: American vs. British, Peking vs. Tientsin, tobacco vs. mining. Both men, as had become obvious in our nightly sessions, had the capacities needed for power, however different they were in character.

As I have already hinted, Montague was the American extrovert. Round of face and body but handsome, always clad in a polo coat, he looked among us like a refugee from a country club. He was cheerful, friendly, immensely talkative, quick in repartee, and full of lively stories. He was seldom unkind, never arrogant, and always the embodiment of charm itself—but like most of us, he was never averse to accepting the best room or the favored treatment his importance deserved.

I remember seeing his stout form running down a street the day we were being housed by the Japanese. Out of curiosity as to whither he was bound, I followed. Soon I saw him grab a slight, elegant gentleman by the elbow. Immediately I recognized Dr. Charles Foster, the immensely respected and modest American surgeon. Montague propelled that puzzled but ever dignified gentleman at great speed over to a marvelously private room for two that Montague had just spied. When the Japanese arrived a moment later, Montague assured them that “the overburdened doctor must have quiet and privacy, and has asked me to join him in here.” I think he really believed it himself when he said it. But Montague was, more than most of us, lovable as well as sharp, and I never doubted that his heart was in the right place. Certainly he was more than usually intelligent as well as decisive, and when pressed had a very strong sense of responsibility to his community.

Chesterton was as different from Montague as night from day.

A small, thin man with an immensely ugly and sad face, he was as deliberate, both in physical movement and in speech, as Montague was fast. In our meetings, when Montague spoke, he would have the whole room in gales of laughter through his sparkling wit. Chesterton would sit there glumly silent until he was ready to pronounce. Finally, when he did speak, his surprisingly deep voice came out so slowly he was inclined to make me feel impatient and bored in the waits between the carefully deliberated words. And yet, there was no question of his inherent power. Except in those instances when Montague disagreed with him, the men seemed instinctively to follow Chesterton’s lead. I observed that the discussion of any subject almost always terminated after one of Chesterton’s authoritative pronouncements.

These two very diverse men were evidently those most liberally supplied with whatever it is that produces personal power and the leadership that is its consequence. It was they who gradually came completely to dominate our sessions. Which of the two would ultimately become the more potent figure was endlessly debated among us. Thus, although all of us in that room were immersed in our own little dramas, each of us would look regularly over to the corner where the tussle for General Affairs was proceeding to see who would, in the end, be Caesar.

It turned out to be the sad-faced Englishman who arose and called the meeting to order. Speaking in his leaden-paced drawl, Chesterton announced his own “chairmanship of the internment center,” and then apparently felt he must say a few further words on the attitude he intended to manifest as our leader.

“Colleagues in leadership,” he began, “I wish to impress upon you how honored and touched I am to be designated for this significant work. I realize that now responsibility for the health and well-being, not to say the lives, of ourselves and our loved ones rests directly upon my shoulders. I shall not disappoint your expectations and hopes; I have shouldered heavy burdens before, and am happy to bear this load for you. And I promise that whatever the temptations that beset a man in high office, I shall rule the camp in strict accordance with our great British tradition of justice and fair play!”

The room rang with muffled “Hear, hears!” as on this solemn (and carefully prepared!) note, our political life began.

As an admirer of Montague’s unique abilities to get whatever he wanted in almost any situation, and somewhat shaken by the heavy pomposity of the acceptance oration, I could only conclude as I left that night, that Montague had decided to let Chesterton become top dog because of the preponderance of British in the camp—but of that I will never be sure.

The next morning the first real joke of camp life broke.

When the names were handed in and the Japanese explained further what the duties of each committee would be, it became plain that the General Affairs Committee, far from being the coordinating center for general camp policy, was merely to be caretaker of certain leftover items. As the astonished Japanese said, “This man is not to be ‘boss’! He is to rule over such things as sports, the sewing room, the barber shop, the library, and the canteen!”

Poor Chesterton had been wrecked on a semantic reef: “Miscellaneous Affairs” had been mistranslated “General Affairs.”

When this coveted prize, over which our giants had fought, turned out to be miniscule, the camp hooted with derisive delight.

Chesterton, the victor, was not merely embarrassed but downright sulky about it. He promptly announced his resignation, indicating that now that he understood what the job involved, he saw that it was too small for a man of his stature. At this the camp hooted once more; Chesterton never acquired political prominence again. Needless to say, Montague, holding his sides and weak from laughter, thanked his lucky stars that he had not been tapped for the honor!

Thenceforth the General Affairs Committee was run by another Britisher, a modest, younger vice president of one of the Tientsin banks.

The vision of a single political leader of the camp vanished never to appear again.

In this bumbling way, the official camp organization was formed. From that time on, there were nine internee committees, each with a chairman and one or two assistants who negotiated directly with the Japanese. The job of each committee was, on the one hand, to press the Japanese for better equipment and supplies and, on the other, to manage the life of the camp in its area. Thus the needs of the camp began to be dealt with by designated men. The amorphous labor force was organized; the problems of equipment and of sanitation were handled by the engineers; supplies were distributed more fairly and efficiently; the complex problems of housing began to be tackled; and schools were started for our three hundred or more children.

With such centralized organization, our community began to show the first signs of a dawning civilization; it was slowly becoming capable of that degree of coordinated work necessary to supply services essential to life and to provide at least a bearable level of comfort.

By the middle of April, moreover, the camp cleaning force had cleared away all the rubble and debris. Most of the dismal ugliness that had greeted us in March disappeared. At this transformation, the garden-loving British began to spring to action. You could see them everywhere—in front of their dorms or along their row of rooms; around the church or the ballfield, turning up soil wherever they could establish claim to a plot of ground, planting the seeds which they had brought from Peking and Tientsin, and then lovingly watering the first signs of new life. In the same spirit, other families would begin to survey the small plot of ground in front of their rooms, planning patios made of scrounged bricks, and experimenting with awnings fashioned from mats purchased in the canteen—all of this, apparently, spurred on by the prospect of summer “teas.” I could feel a new warmth in the wind and see a new brightness in the air wherever I went.

About the same time, evening lecture programs for adults sprouted in every available empty room. These talks touched on a wide variety of subjects, from sailing and woodwork, art and market research to theology and Russian, on which there were unemployed experts both willing and eager to speak. Concurrently, our weekly entertainments began. These took place in the church, starting with simple song fests and amateur vaudeville skits. The culmination of these early forms of “culture” came, surely, when a baseball league (e.g., the Peking Panthers vs. the Tientsin Tigers) started in earnest on the small ballfield, exciting the whole population two or three afternoons a week.

...

[further reading] ...

copy/paste into your internet browser ...

http://www.weihsien-paintings.org/books/Gilkey/BOOK/Gilkey-BOOK(WEB).pdf

#