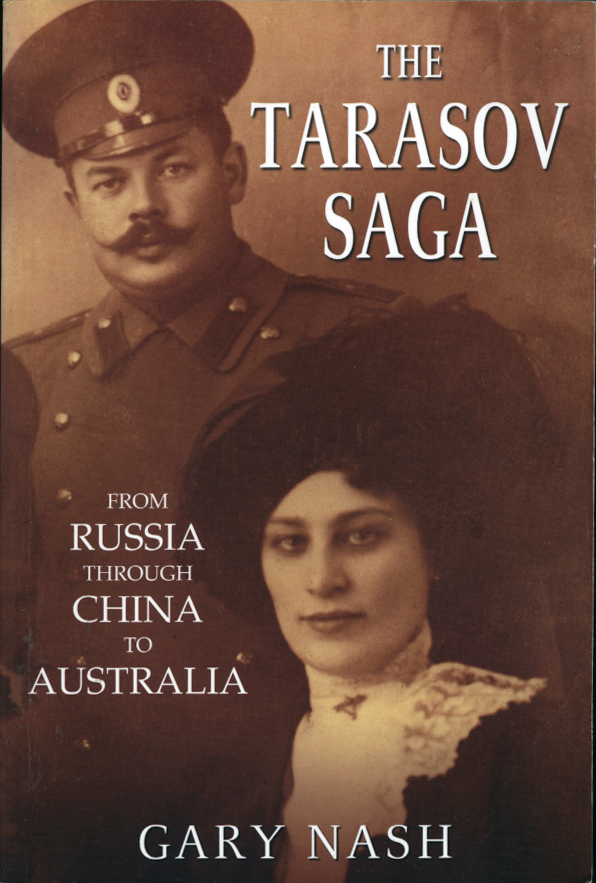

"The Tarasov Saga"

by Gary Nash

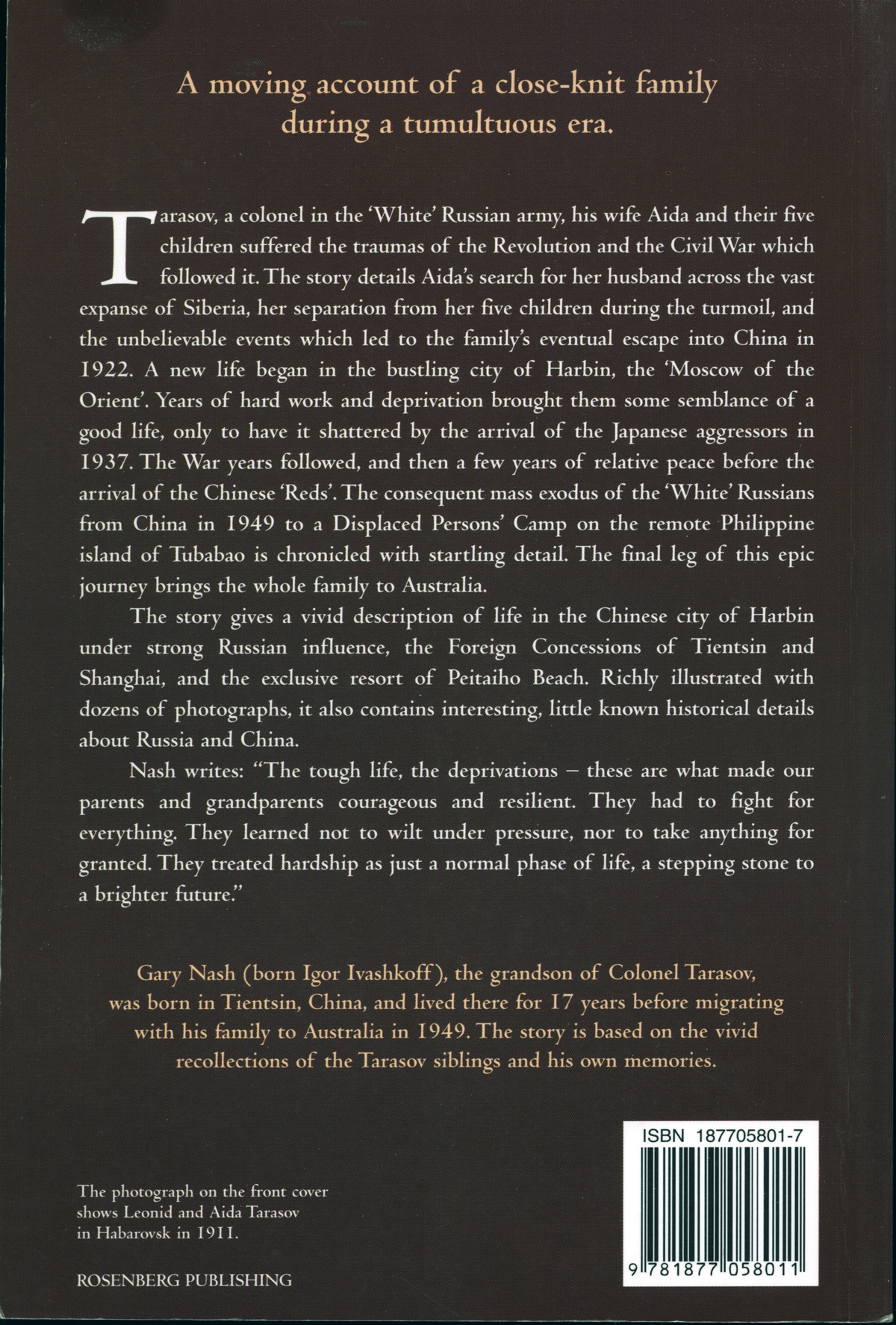

A moving account of a close-knit family during a tumultuous era.

Tarasov, a colonel in the `White' Russian army, his wife Aida and their five

children suffered the traumas of the Revolution and the Civil War which

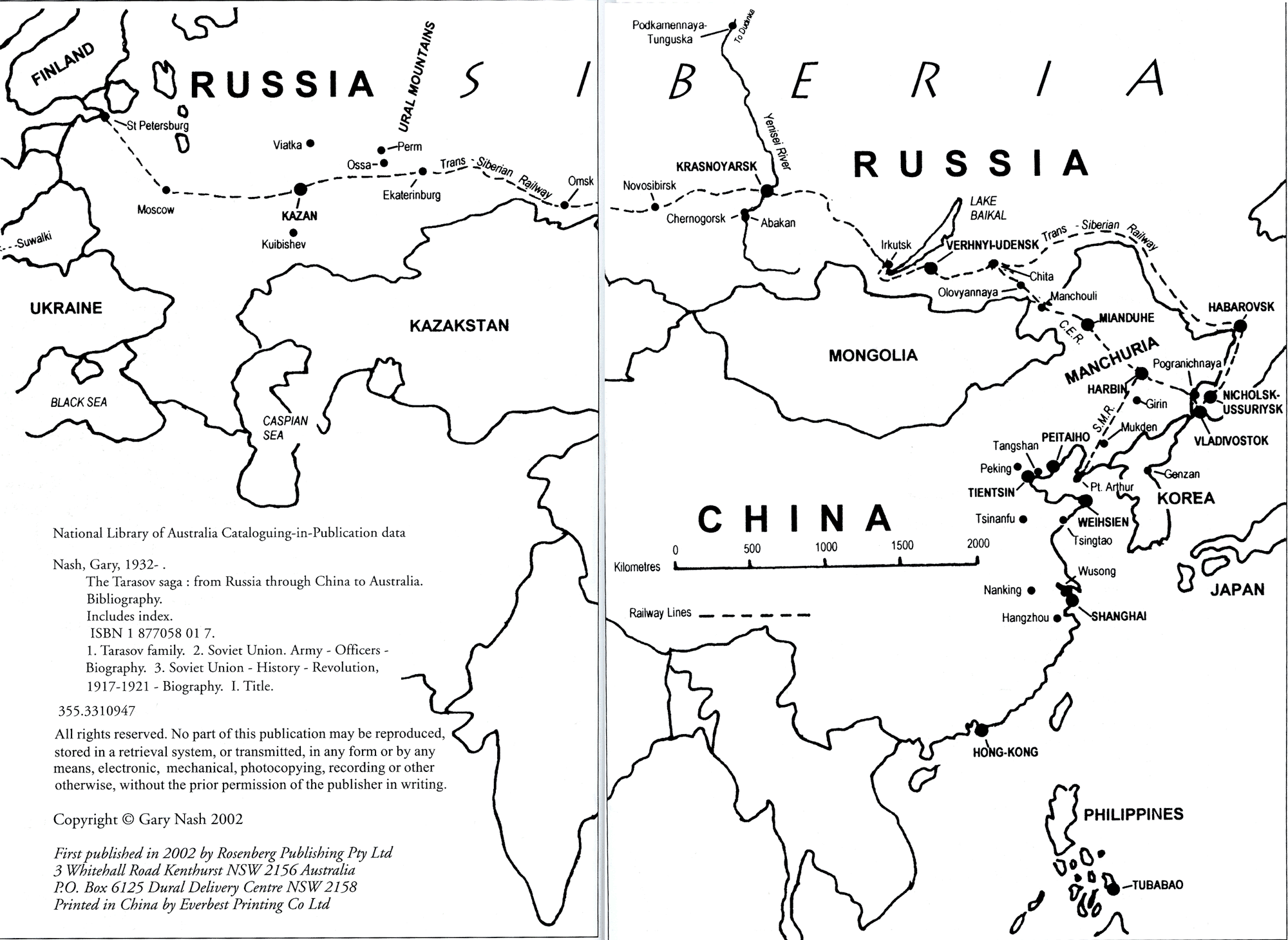

followed it. The story details Aida's search for her husband across the vast expanse of Siberia, her separation from her five children during the turmoil, and the unbelievable events which led to the family's eventual escape into China in I922. A new life began in the bustling city of Harbin, the `Moscow of the Orient'. Years of hard work and deprivation brought them some semblance of a good life, only to have it shattered by the arrival of the Japanese aggressors in I937. The War years followed, and then a few years of relative peace before the arrival of the Chinese `Reds'. The consequent mass exodus of the `White' Russians from China in I949 to a Displaced Persons' Camp on the remote Philippine island of Tubabao is chronicled with startling detail. The final leg of this epic journey brings the whole family to Australia.

The story gives a vivid description of life in the Chinese city of Harbin under strong Russian influence, the Foreign Concessions of Tientsin and Shanghai, and the exclusive resort of Peitaiho Beach. Richly illustrated with dozens of photographs, it also contains interesting, little known historical details about Russia and China.

Nash writes: "The tough life, the deprivations — these are what made our parents and grandparents courageous and resilient. They had to fight for everything. They learned not to wilt under pressure, nor to take anything for granted. They treated hardship as just a normal phase of life, a stepping stone to a brighter future:'

Gary Nash (born Igor Ivashkoff), the grandson of Colonel Tarasov, was born in Tientsin, China, and lived there for 17 years before migrating with his family to Australia in I949. The story is based on the vivid recollections of the Tarasov siblings and his own memories.

ISBN 187705801-7The photograph on the front cover shows Leonid and Aida Tarasov in Habarovsk in 1911.

ROSENBERG PUBLISHING

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data

Nash, Gary, 1932- .

The Tarasov saga : from Russia through China to Australia. Bibliography. Includes index.

ISBN 1 877058 01 7.

1. Tarasov family. 2. Soviet Union. Army - Officers - Biography. 3. Soviet Union - History - Revolution, 1917-1921 - Biography. I. Title. 355.3310947

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

Copyright © Gary Nash 2002

First published in 2002 by Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd 3 Whitehall Road Kenthurst NSW 2156Australia

P.O. Box 6125 Dural Delivery Centre NSW 2158 Printed in China by Everbest Printing Co Ltd

CONTENTS

FOREWORD 6

1

RUSSIA (1900-1922) 13

Turbulent Times: 1900-1905 13

Birth of the Tarasov Clan: 1906-1911 16

Two Wars: 1905-1915 18

Catastrophe in Kazan: 1915-1918 20

Revolution! — 1917-1918 24

The Search for Husband and Father: 1919 25

Five Little Orphans: 1920-1922 32

The Search for Mother: 1920 35

The 'Orphan Train': 1922 39

The Railway Town: 1922 42

Reunion: 1922 45

2

CHINA (1922-1937) 49

Harbin — 'Moscow of the Orient' 49

A New Beginning: 1922 52

The Loveless Marriage: 1926 56

Tientsin — 'Ford of Heaven': 1926-1928 59

The Entrepreneur: 1927-1930 68

True Love: 1929 70

Shanghai — the 'Yellow Babylon' 73

Bodyguards: 1930 78

Feared, but not Loved 79

A Terrible Omen: 1930 82

The Happy Event: 1932 84

The Incurable Romantic: 1932-1933 87

The Landlady and the Lover: 1933 89

Manchuria, the Russians and the Japanese: 1917-1932 93

To Die so Young: 1934 97

More Problems in Harbin: 1935-1936 102

Abandoned! — 1935-1939 104

Peitaiho Beach: 1936-1939 106

3

THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION 1937–/945) 113

The Invasion: 1937-1939 113

Playing God: 1939 116

The Big Flood: 1939 117

St Louis College: 1937-1941 122

My World of Music: 1939 128

Life in the 'Yellow Babylon': 1930-1940 130

We Want You to Be a Spy! – 1939 134

Peitaiho Beach Happenings: 1940 136

My Naked Aunt: 1941 138

The Soothsayer: 1941 139

Armbands for the Enemy: 1942-1943 141 Malaria! — 1942 143

Paralysed! — 1942-1944 145

An Unwanted Pregnancy: 1942-1943 146

The Secret Wedding: 1943 147

Life in Harbin: 1942-1944 148

Rationing: 1942-1944 151

The Civil Defence Corps: 1942-1944 153

Epilepsy!— 1938-1944 155

Simple Pleasures: 1943-1944 158

The Art of Bribery: 1944-1945 160

My Step-Grandfather: 1942-1944 162

Learning Russian: 1943 163

The Perilous Gamble: 1943 164

Internment Camps: 1943-1945 — 167

167

4

AFTER THE WAR (1945-1949) 170

End of the War: 1945-1946 170

Playing God Again: 1946 174

The Retarded Child: 1946 174

Off to Mianduhe: 1947 176

Gone Without a Word: 1947 179

Asad Tale: 1947 180

Best of Friends: 1945-1948 182

Sex Education, Lack of: 1945-1948 185

A Cruel Punishment: 1946 186

Risk-Taking: 1947 188

Growing Up, Tientsin-^tyle: 1945 191

A Marriage in Crisis: 1946-1947 193

Millionaires Galore! 1946-1949 195

Summer Jobs: 1945-1947 197

Towards Graduation: 1947-1948 198

Welcome to Russia! 1947 199

The 'Holiday Camp': 1947-1949 202

Two Years of Misery: 1947-1948 203

5

EXODUS ( 1948-1951) 206

The Exodus Begins: 1948 206

Tubabao, a Haven for Refugees: 1948 209

Fleeing from China: 1949 210

Life on a Desert Island: 1949 211

The Great TB Scam: 1949 221

A Long Wait for Asylum: 1949 223

Shanghai: 1949-1950 225

Farewell, Yellow Babylon! 1950-1951 227

6

THE STRAGGLERS (1950-1954) 232

Life Was Not Meant to Be Easy: 1950-1952 232

A Brush With Death: 1950 234

The Ex-Convict: 1950 236

A Maritime Career: 1950 237

'Shamanism': 1952 239

Those Lost Years 242

A Marriage of Convenience: 1952-1953 244

The Sorceress: 1954 246

The Final Exodus: 1954 248

7

AUSTRALiA, LAND OF OPPORTUNITY 251

Settling Down 251

Pianist or Engineer? 252

Re-Christening! 254

The Alcoholic 255

Nadia and Len 257

My First Car 258

An Early Marriage 259

Divine Intervention 262

Our Own House! 263

My New Name 264

Thank You, Australia! 265

EPILOGUE 266

Acknowledgments 273

Bibliography 273

INDEX 274

FOREWORD 6

1

RUSSIA (1900-1922) 13

Turbulent Times: 1900-1905 13

Birth of the Tarasov Clan: 1906-1911 16

Two Wars: 1905-1915 18

Catastrophe in Kazan: 1915-1918 20

Revolution! — 1917-1918 24

The Search for Husband and Father: 1919 25

Five Little Orphans: 1920-1922 32

The Search for Mother: 1920 35

The 'Orphan Train': 1922 39

The Railway Town: 1922 42

Reunion: 1922 45

2

CHINA (1922-1937) 49

Harbin — 'Moscow of the Orient' 49

A New Beginning: 1922 52

The Loveless Marriage: 1926 56

Tientsin — 'Ford of Heaven': 1926-1928 59

The Entrepreneur: 1927-1930 68

True Love: 1929 70

Shanghai — the 'Yellow Babylon' 73

Bodyguards: 1930 78

Feared, but not Loved 79

A Terrible Omen: 1930 82

The Happy Event: 1932 84

The Incurable Romantic: 1932-1933 87

The Landlady and the Lover: 1933 89

Manchuria, the Russians and the Japanese: 1917-1932 93

To Die so Young: 1934 97

More Problems in Harbin: 1935-1936 102

Abandoned! — 1935-1939 104

Peitaiho Beach: 1936-1939 106

3

THE JAPANESE OCCUPATION 1937–/945) 113

The Invasion: 1937-1939 113

Playing God: 1939 116

The Big Flood: 1939 117

St Louis College: 1937-1941 122

My World of Music: 1939 128

Life in the 'Yellow Babylon': 1930-1940 130

We Want You to Be a Spy! – 1939 134

Peitaiho Beach Happenings: 1940 136

My Naked Aunt: 1941 138

The Soothsayer: 1941 139

Armbands for the Enemy: 1942-1943 141 Malaria! — 1942 143

Paralysed! — 1942-1944 145

An Unwanted Pregnancy: 1942-1943 146

The Secret Wedding: 1943 147

Life in Harbin: 1942-1944 148

Rationing: 1942-1944 151

The Civil Defence Corps: 1942-1944 153

Epilepsy!— 1938-1944 155

Simple Pleasures: 1943-1944 158

The Art of Bribery: 1944-1945 160

My Step-Grandfather: 1942-1944 162

Learning Russian: 1943 163

The Perilous Gamble: 1943 164

Internment Camps: 1943-1945 —

167

1674

AFTER THE WAR (1945-1949) 170

End of the War: 1945-1946 170

Playing God Again: 1946 174

The Retarded Child: 1946 174

Off to Mianduhe: 1947 176

Gone Without a Word: 1947 179

Asad Tale: 1947 180

Best of Friends: 1945-1948 182

Sex Education, Lack of: 1945-1948 185

A Cruel Punishment: 1946 186

Risk-Taking: 1947 188

Growing Up, Tientsin-^tyle: 1945 191

A Marriage in Crisis: 1946-1947 193

Millionaires Galore! 1946-1949 195

Summer Jobs: 1945-1947 197

Towards Graduation: 1947-1948 198

Welcome to Russia! 1947 199

The 'Holiday Camp': 1947-1949 202

Two Years of Misery: 1947-1948 203

5

EXODUS ( 1948-1951) 206

The Exodus Begins: 1948 206

Tubabao, a Haven for Refugees: 1948 209

Fleeing from China: 1949 210

Life on a Desert Island: 1949 211

The Great TB Scam: 1949 221

A Long Wait for Asylum: 1949 223

Shanghai: 1949-1950 225

Farewell, Yellow Babylon! 1950-1951 227

6

THE STRAGGLERS (1950-1954) 232

Life Was Not Meant to Be Easy: 1950-1952 232

A Brush With Death: 1950 234

The Ex-Convict: 1950 236

A Maritime Career: 1950 237

'Shamanism': 1952 239

Those Lost Years 242

A Marriage of Convenience: 1952-1953 244

The Sorceress: 1954 246

The Final Exodus: 1954 248

7

AUSTRALiA, LAND OF OPPORTUNITY 251

Settling Down 251

Pianist or Engineer? 252

Re-Christening! 254

The Alcoholic 255

Nadia and Len 257

My First Car 258

An Early Marriage 259

Divine Intervention 262

Our Own House! 263

My New Name 264

Thank You, Australia! 265

EPILOGUE 266

Acknowledgments 273

Bibliography 273

INDEX 274

FOREWORD

Just imagine if someone came up to you and told you that you and your family were to be deported to Bangladesh in a week's time to start a new life, and that all you could take with you was one suitcase and one hundred dollars.

'Yes, we know you can't speak Bengali, but you'll pick it up.'

And then, after a couple of decades of hard work building up your life there, you would be told to do the same again by moving to Lower Slobovia or somewhere similar.

'Yes, we know you can't speak Lower Slobovian, but ...'

It's hard to imagine, isn't it? But that's exactly what happened to the Tarasovs and to millions of other refugees from last century's wars.

We live now in a wonderful country called Australia. Most of us have a good life. None of us is starving. Most of us own a house. Just about everyone owns a car or two. All of us have personal and political freedom. It is easy to feel that this sort of life is par for the course — that this is the way it's supposed to be — and to forget that it was not always so, especially for those who emigrated here from war-ravaged countries.

It's only when we look back at the deprivations suffered by our parents and their parents that we realise how different their lives were from ours. Most of what we take for granted was impossible for them. Many of what we consider to be the necessities of life were either not available to them, or could only be obtained through sacrifices or extraordinary efforts.

The Tarasovs lost just about everything they owned twice in their lifetime. The first time was when they fled from Russia, and the second was when they fled from China. However, there is a positive side. The tough life, the deprivations — these experiences made our parents and grandparents courageous and resilient. That's what built their character. They had to fight

for everything. They learned not to wilt under pressure, not to take anything for granted.

They learned to be gutsy.

I have nothing but the highest admiration for the Tarasovs. From the outbreak of World War I nothing was ever proffered to them on a silver platter. But they never complained about their lot. They treated hardship as if it were a normal phase of life, as a stepping stone to a brighter future. They were grateful for the good times when and if they did come, and I am honoured to be a member of this family.

Let me say something about how this book came about. Throughout my life I used to hear my mother and my aunts and uncles talk about the old times, about their life in Russia and China. I always listened with fascination. Grandma Aida had a wonderful memory, and she often told us stories about the early days. She died in 1979 at the age of ninety and many of her memories would have been lost had it not been for my Aunt Jenia, who lived with Aida during the last years of her life and who also had an excellent memory. She was able to recall much of what Aida had told her.

'Someone should write a book about the Tarasovs,' my mother, Nina, often said. But that's as far as it went. However, when I retired in 1990 I decided that it was time for me to do something about it. I informed the tribe that I was planning to write 'the book' and, to my delight, the news was greeted with enthusiasm. As my mother and her four siblings were all alive and living in Sydney, and so was I, there would obviously be no difficulty, I thought, in obtaining all the material I needed.

But such was not the case. All of them loved talking about old times during our warm, cosy family gatherings, but to get them to either write things down or record them on tape was like pulling teeth. All sorts of excuses were given

everything from 'I don't remember' to 'I don't have the time now' to 'Why don't you ask Jenia? Her memory is better than mine.'

Finally, and stupidly, I lost patience with the lot of them and gave the project up. Every so often I would raise the subject again, but the earlier enthusiasm had vanished.

An unfortunate event was the catalyst to get things moving again. Nusia, my oldest aunt, contracted cancer and went into hospital for a few weeks. When I visited her, she asked me to bring her an exercise book. It's pretty boring in hospital,' she said. 'I think I'll start writing a few things down about my life.' And write she did. Her first contribution was twenty-four foolscap pages of Russian longhand.

Eureka! The belated beginning! I immediately translated it, asked her some questions to fill in the gaps and gave a copy to her three sisters for their comments. The ball started rolling. Every time I received some input, I circulated it to the other members of the family who added further details. And so it went.

The book would have been completed sooner had I not become immersed

in other activities. What reinstated it to a higher priority was the death of Nusia in February 1997 and my mother's advancing Alzheimer's disease. I suddenly realised that I was in danger of losing my links to the past. I still had some holes in the book, and it was going to be now or never. By the time I completed it, my uncle Len had died at the age of ninety and my mother had passed away at the age of ninety-two.

I hope that the resulting story will do justice to the Tarasov family and be of interest to those who would like to read about the trials and tribulations of a Russian family during the first half of the twentieth century.

Author's note.

The spelling of Chinese names proved to be a bit of a problem. There are two 'official' romanised systems of spelling them. The first, developed in the second half of the nineteenth century by Sir Thomas Francis Wade and subsequently modified by Herbert Allen Giles in 1912, is called the 'Wade-Giles'. The second, called 'Pinjin', was introduced in 1956 and officially adopted by the People's Republic of China in 1979. And then there was the way we spelt the names when we were living in China, which was often different from the other two. For example, 'Tientsin' was our spelling of that city, but in the Wade–Giles system it is 'T'ien-ching' and in the Pinyin system 'Tianjin'. In some cases, the differences are significant — 'Canton', as we knew it, is transformed to 'Kuanghchou' and 'Guangzhou', respectively, and 'Hong Kong' into 'Hsiang-kang' and 'Xianggang'.

Very confusing!

So I have decided to use the spellings we, the foreign inhabitants of China, used during the period covered by the book. In deference to scholars among the readers, when the name is first used in the book I have also included the Pinyin version in brackets (when it is different).

I have also included this version in the Index.