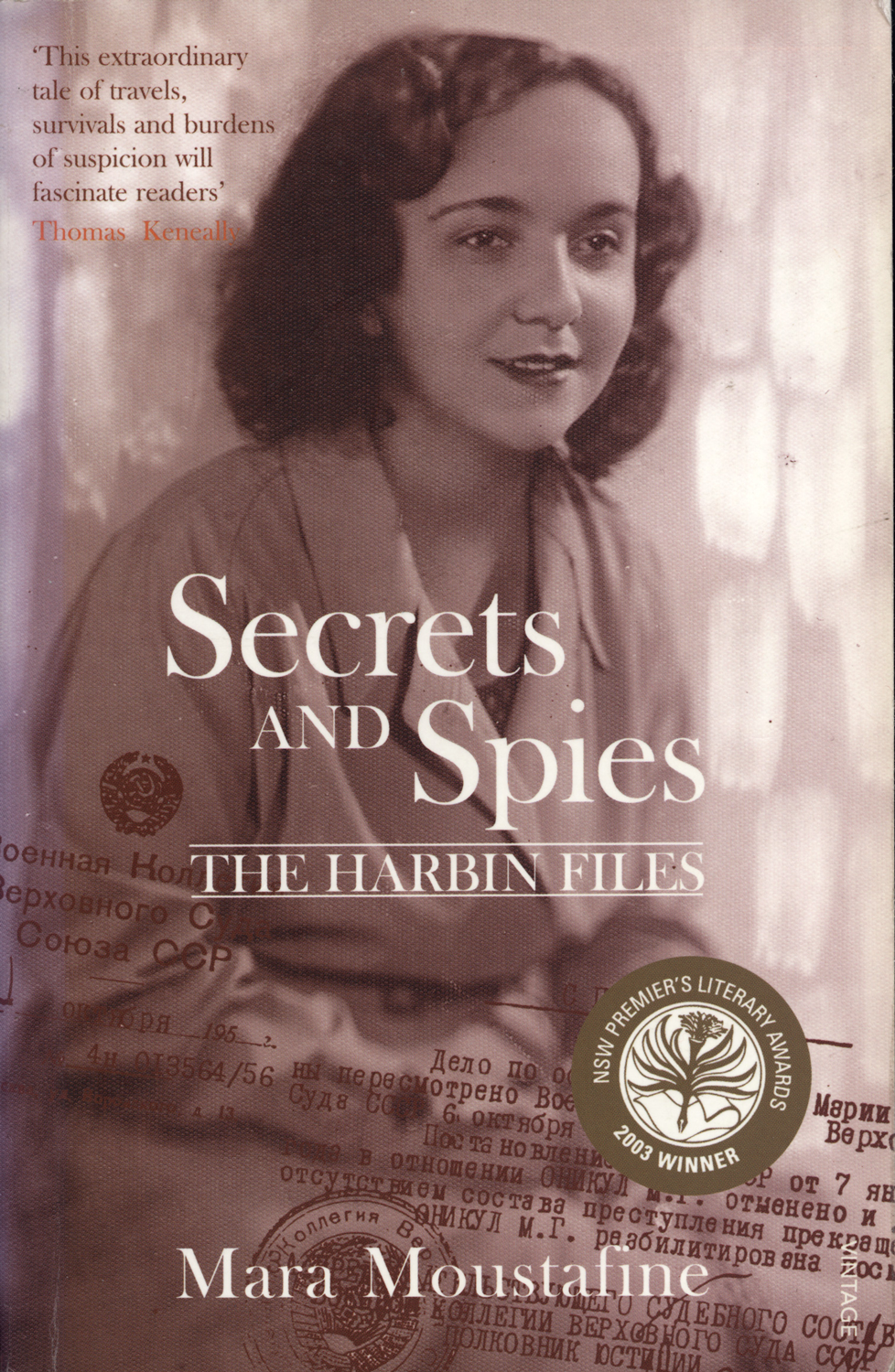

"SECRETS

and SPIES"

by Mara Moustafine

A Vintage Book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Hwy, North Sydney NSW 2060

http://www.ramiornhouse.com.au

Sydney New York Toronto London Auckland Johannesburg

Copyright 0 Mara Moustafine 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication

data:

ISBN: 978 1 74051 091 2

ISBN: 1 74051 091 7

Moustafine, Mara. 2. Consultants — Australia — Biography. 3. Russians — China — Harbin. 4. Political persecution — Soviet Union. I. Title

920.72

Cover photograph of Manya Onikul, courtesy of Mara Moustafine

Cover design by Justine O'Donnell for jmedia design

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough,Victoria

Printed and bound by The SOS Print & Media Group

10 9 8 7 6 5

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Hwy, North Sydney NSW 2060

http://www.ramiornhouse.com.au

Sydney New York Toronto London Auckland Johannesburg

Copyright 0 Mara Moustafine 2002

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication

data:

ISBN: 978 1 74051 091 2

ISBN: 1 74051 091 7

Moustafine, Mara. 2. Consultants — Australia — Biography. 3. Russians — China — Harbin. 4. Political persecution — Soviet Union. I. Title

920.72

Cover photograph of Manya Onikul, courtesy of Mara Moustafine

Cover design by Justine O'Donnell for jmedia design

Typeset by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough,Victoria

Printed and bound by The SOS Print & Media Group

10 9 8 7 6 5

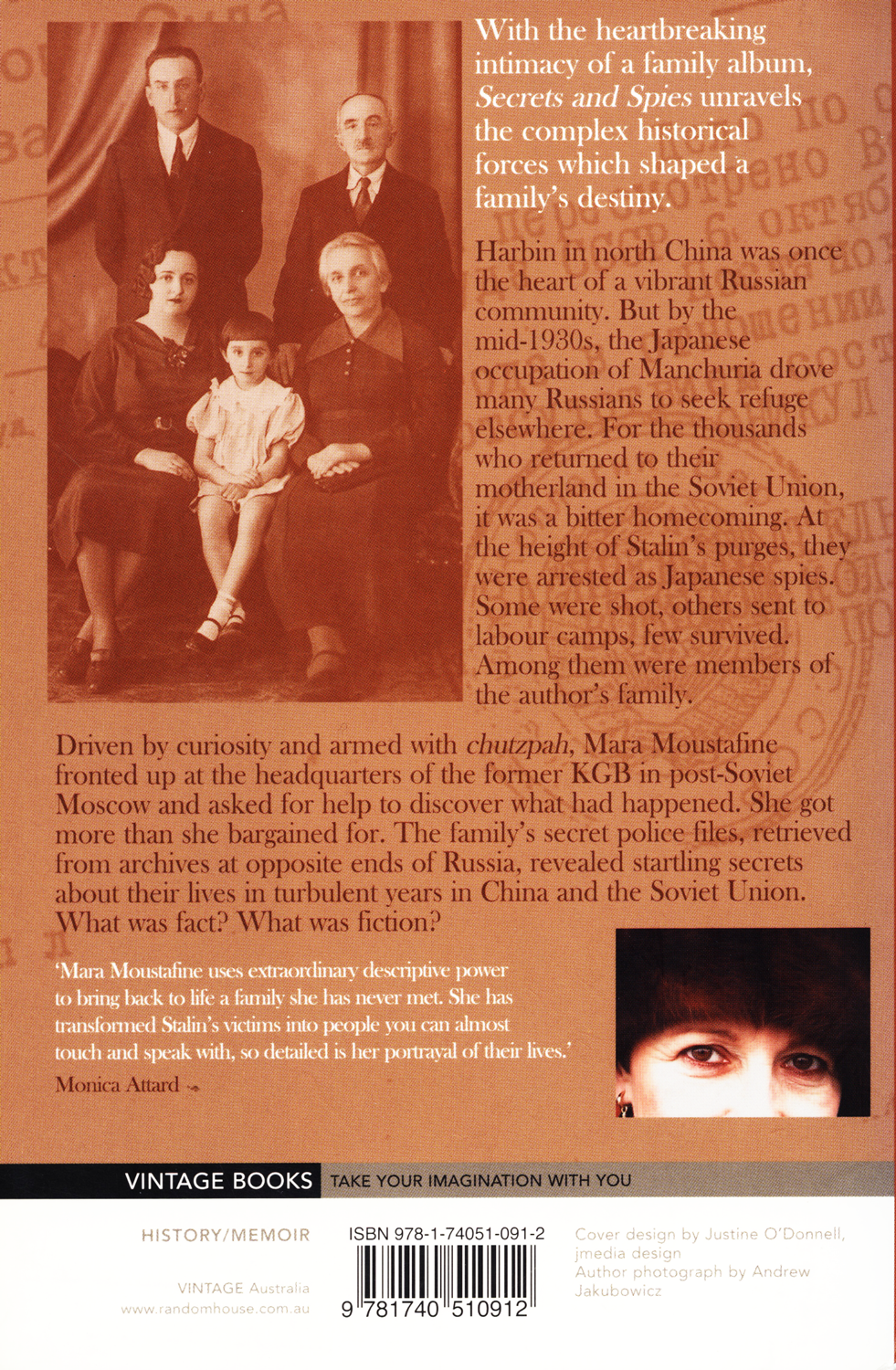

With the heartbreaking intimacy of a family album, Secrets and Spies unravels the complex historical forces which shaped a family's destiny.

Harbin in north China was once the heart of a vibrant Russian community. But by the mid-1930s, the Japanese occupation of Manchuria drove many Russians to seek refuge elsewhere. For the thousands who returned to their motherland in the Soviet Union, it was a bitter home coming. At the height of Stalin's purges, they were arrested as Japanese spies. Some were shot, others sent to labour camps, few survived.

Among them were members of the author's family.

Driven by curiosity and armed with chutzpah, Mara Moustafine fronted up at headquarters of the former KGB in post-Soviet Moscow and asked for help to discover what had happened. She got more than she bargained for. The family's secret police files, retrieved from archives at oposite ends of Russia, revealed startling secrets about their lives in turbulent years in China and the Soviet Union.

What was fact? What was fiction?

'Mara Moustafine uses extraordinary descriptive power to bring back to life a family she has never met. She has transformed Stalin's victims into people you can almost touch and speak with, so detailed is her portrayal of their lives.'

Monica Attard.'Secrets and Spies is a cry from the heart. Every page took me further and deeper into an experience I'd not had before, not even after four years in Russia, listening to the horror stories of people who, though their souls had taken a beating, had survived Stalinism—the darkest of the dark years. Mara Moustafine uses extraordinary descriptive power to bring back to life a family she has never met. She has transformed Stalin's victims into people you can almost touch and speak with, so detailed is her portrayal of their lives. The research is impeccable. The story com-pelling. Each page is a passionate tribute to a family defiant till death against a machine so insidious that its leader was mourned when he died. Secrets and Spies is a protest, an expression of indignation at the inhumanity of one of this century's worst evils. It is a tribute to Moustafine and the past she has turned into a present.'

Monica Attard,

ABC journalist and author of

Russia: Which Way Paradise,

Transworld, 1997

ABC journalist and author of

Russia: Which Way Paradise,

Transworld, 1997

'Secrets and Spies is an extraordinary book and contains an enormous series of moral lessons ... I've read many family histories but none of them have the maturity and depth of this one. Often a family history is filled with personal anguish but there is a simplicity to it which makes it difficult to draw from it what is really happening in the wider world. Because of her background, Mara Moustafine is able to set the scene of a family drawn into

the vortex of the most tragic events of the last century. She has the capacity for clinical, independent-minded research and broad moral judgement that enables her to do justice to the horror of her family's story.'

The Hon Kim C. Beazley

Former deputy prime minister and former

leader of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party

Former deputy prime minister and former

leader of the Federal Parliamentary Labor Party

[Moustafine's] gripping chronicle balances the personal impact of discovery with skilled geopolitical analysis ... Secrets and Spies certainly delivers on its promise of unveiling lethal conspiracies. But it is the Darwinian struggle of ordinary people against overwhelming historical odds that grabs the attention.'

Felicity Bloch,

Sydney Morning Herald

Sydney Morning Herald

Biography

Mara Moustafine was born in Harbin, China, into a family with Jewish, Russian and Tatar roots and came to Sydney as a child in 1959.

Bilingual in Russian and English, Mara completed a Masters in International Relations at the Australian National University. She has worked as a diplomat, intelligence analyst, journalist and a senior business executive in Australia and Asia.

This is her first book.

CONTENTS

FAMILY TREE X

MAPS XII

GLOSSARY XV

KEY HISTORICAL DATES XIX

KEY HISTORICAL FIGURES XXIII

PROLOGUE

Curiosity 1

CHAPTER I

Riga Treasures 11

CHAPTER 2

Gorky Tears 35

CHAPTER 3

On the Steppes of Manchuria 67

CHAPTER 4

Coming Apart 89

CHAPTER 5

From Manchukuo to the Radiant Future 109

CHAPTER 6

Black Ravens in October 135

CHAPTER 7

Japanese Spies in Gorky 150

CHAPTER 8

The Ravens Return 181

CHAPTER 9

'All Harbintsy are Subject to Arrest' 201

CHAPTER 1O

The Survivor 213

CHAPTER 11

Our Man in Khabarovsk 242

CHAPTER 12

Spies in the Far East 272

CHAPTER 13

Redemption 317

CHAPTER 14

Back to Harbin 335

CHAPTER 15

Khrushchev's 'Virgin Lands' or Sydney? 373

CHAPTER 16

Continuity 401

NOTES 425

THE HARBIN ORDER 449

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 453

INDEX 457

Prologue

Curiosity

I DIDN'T KNOW much about her when, in my early twenties, I stole her photograph from my grandmother's drawer. But I sensed she was important to me somehow. I carefully slid the picture into the tiny Chinese leather album with cut-out frames I had found among my family's treasures from Harbin.

Manya was my grandmother Gita's younger sister. Her photograph was a perfect fit for the small rectangular space next to the picture Gita had inscribed to my grandfather four months before their marriage in 1927.

At seventeen, Gita was a classic beauty. Her dark, knowing eyes stared directly out of the photo with a quiet certainty. But her simple, sombre dress with white lace collar — perhaps her school uniform — gave away her wholesome innocence. I adored my grandmother, but could never imagine living her life, defined as it was by marriage and family.

Manya was quite different. Photographed in her early twenties, she looked more worldly-wise and modern. Dressed in an open-necked trench coat, with dark shoulder-length hair, Manya had a certain 1930s glamour. Gazing mysteriously into the distance, she looked like she was going places. Though I had never known her, Manya struck me as someone I could relate to.

Why didn't I ask my grandmother for the photo? I knew there was nothing she would ever deny me. But instinct told me there would be less pain caused this way. Besides, I did not know how to explain why I was filling the little album with photographs of myself and my family. Some had been taken in Sydney, but most were from Harbin, the city in north China where several generations of my family had lived and where I was born. At that stage, my fascination with the lost world of Russian Harbin was still ill-defined. And my vague yearning to connect to family across continents and generations was something I had not articulated, even to myself.

Russian Jews have a tradition of naming a child after a dead relative. I am named after Manya, whose full name in Russian was Maria. They called me Marianna as this name derives from the same Hebrew root as Maria — shortened in my case to the Russian 'Mara'. Why not `Manya'? In 1950s Harbin, my family thought it too reminiscent of the shtetls (Jewish villages) of Byelorussia, which my great-grandparents had left behind — together with poverty and pogroms — at the turn of the twentieth century.

All I knew about Manya when I was growing up was that she had been a dentist and had died in Stalin's purges along with her father, Girsh, and brother, Abram. She was twenty-six years old. 'What was she like? Why did they kill her?' I remember asking. The most I ever got in reply was, 'She wasn't as beautiful as your grandmother, but she was very clever. As for her death — you know she died in the purges. Stalin didn't need a reason.'

From my grandmother's stories, I knew that in the mid-1930s, Manya, her parents Girsh and Chesna Onikul, and two brothers Abram and Yasha, left Hailar, a small town in the Manchurian steppes north-west of Harbin, to escape the Japanese occupation and build a new life in the Soviet Union. Gita, who was already married, stayed in Harbin with my grandfather, Motya Zaretsky, and my mother, Inna.

The Onikuls went to Gorky, the city I knew as the place of exile in the 1980s of the Nobel Prize-winning human rights activist Andrei Sakharov. Formerly Nizhny Novgorod, the city was renamed in Soviet times after the proletarian writer Maxim Gorky, who was born there. How appropriate that in Russian gorky means 'bitter'. In hindsight, it seems bizarre that, after twenty-five years in Manchuria, the Onikuls chose to go there on the eve of the Great Terror. But life in Manchuria under Japanese occupation in the 1930s was full of menace for many Russians, particularly those who, like the Onikuls, had Soviet identity papers.

In the late 1930s, a wall of silence descended between the Onikuls, caught in the Stalinist terror followed by the war, and my grandparents, the Zaretskys, living under

the Japanese puppet regime in 'Manchukuo'. Only in the mid-1950s, after the death of Stalin, did news reach Harbin that two of the Onikuls—Gita's mother, Chesna, and her younger brother, Yasha — had survived the purges. By some miracle, in the late 1950s, each separately visited Harbin from Riga, the capital of Latvia where they were then living. Chesna brought the news that her husband, Girsh, and two other children, Manya and Abram, had perished. I was too young then to understand what was going on.

In 1959, a couple of years after these visits, my family left Harbin for Australia. By that time, the once thriving Russian community had become an anachronistic enclave of some one thousand people. The Chinese Revolution was in full swing and we were not wanted.

Growing up Russian in Sydney in the 1960s, one couldn't escape reminders of the Cold War world. The spy drama that gripped Australia after the defection of two Soviet agents, the Petrovs, in 1954 was still fresh in people's minds. I would often be put on the spot when asked where I came from.

'China,' I would answer.

'That's funny, you don't look Chinese.'

'No, I'm Russian.'

'Are you a Communist?', the next question might be, or 'Are you White Russian or Red Russian?'

These were not the sort of questions most Australian children my age had to field.

'No, I'm Russian from China. I've never even been over there.'

'Yes, but what about your parents?'

'They haven't either.'

The ideological divide between Soviet and émigré Russians was accentuated at Russian school, which I attended on Saturdays for ten years. Organised by Russian Harbintsy (people of Harbin) to ensure their children preserved their heritage, we were taught language, literature and history, as well as singing and ballet. The standard of teaching was generally very high and enabled most of us to take Russian as an extra subject for matriculation. But it had its idiosyncrasies.

Although the text books we used were printed in the Soviet Union, they were censored before they were handed out to us. This meant that all references to the Soviet Union, Communist Party, the Pioneers (a youth group most Soviet children attended), the kolkhoz (col-lective farm) and other Soviet concepts were glued over with paper. So were Soviet symbols in illustrations, such as the Soviet crest with hammer and sickle and even the red stars on top of the Kremlin towers.

Predictably, our study of Russian history, taught by a woman whom we nicknamed 'Catherine the Great' because of her pompadour hairstyle and elaborate dresses, ended with the fall of the House of Romanov in 1917. 'What happened after that?' I remember asking, mischievously. In fact, I knew full-well having already

studied the Bolshevik Revolution at high school. The teacher looked disapproving, as if I had asked her where babies came from, and suggested that I go home and ask my mother.

Still, I knew that 'over there', behind the infamous 'iron curtain', I had relatives whom I would probably never see again. My great-grandmother, Chesna, and my paternal grandmother, Tonya, had died in the Soviet Union in the early 1960s. But Gita's brother Yasha still lived in Riga with his wife Galya. He was some sort of doctor, working for the Soviet airline Aeroflot. He corre-sponded regularly with my grandmother and sometimes sent me books and Latvian souvenirs.

Curiously, the return address on anything Yasha sent us was always in his wife Galya's surname. My mother explained that Yasha was afraid that contact with for-eigners might impinge negatively on his career. I would write him a few lines in my grandmother's letters. Once in the mid-1970s, I mentioned that I had visited Israel, among some other Mediterranean countries. My mother crossed it out. 'But the Soviet Union has diplomatic relations with Israel,' I protested. 'It might still be dangerous for them. You just never know,' she replied.

Such exchanges frequently reminded me how much I took for granted, living in a democratic country where law and logic governed and a premium was placed on a humane and civil society. Letters from our relative, Ira Kogan in Kazakhstan, underlined my family's good fortune to have made it to Australia at all. Still in Harbin in the early 1960s, she and her family had not been able to get Australian entry visas. It could so easily have been our story too.

Perhaps it was my family's history of journeys across borders and political systems which in some part drove me to study politics and international relations at university in the 1970s. I read a lot of Soviet history but my focus was on contemporary Soviet politics and the dynamics of the bipolar world. By the late 1970s, I was working on my Masters degree in international relations at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, with a doctoral scholarship in the offing. It occurred to me then that the stories of Harbin Russians like my family were an invaluable historical source on extraordinary events in Russia and China, and should be recorded. But I was too busy with issues of high policy — US-Soviet détente, the Middle East conflict and Eurocommunism. Set on the path to an academic career, I left the Harbin project on the back-burner, thinking there would always be time for it later.

But halfway through my Masters, I began to question my career direction. Having spent five years in academe, I became impatient to get out into the real world — or at least, the world of diplomacy. To my chagrin, I discovered that the Department of Foreign Affairs was not recruiting new entrants that year. I happened to mention my disappointment to the director of the Australian Institute of International Affairs, a distinguished, retired

ambassador whose office was in my department at university. Several months later, his secretary summoned me from an end-of-year picnic near the lake in the university grounds for an urgent meeting.

'Right now?' I asked in dismay. I was dressed in tight, red jeans and a black T-shirt — the colours of anarchy.

If possible, yes.' I straightened myself up as best I could and went immediately to the distinguished gentleman's office.

'It's about your future, my dear,' he said, reminding me of our earlier conversation. 'Have you ever considered intelligence?'

I was stunned. Only one intelligence agency sprang to mind — ASIO, the domestic security service — not really the place for a committed left-leaning liberal.

'Do I look like the sort of person who would work for ASIO?' I asked.

'Do I look like the sort of person who would recruit for them?' he responded.

'No', I said, thinking 'yes'.

In fact, the organisation the ambassador had in mind was the Office of National Assessments (ONA), a new intelligence assessment organisation set up to provide the government with strategic analysis on international matters. Sensing my hesitation, he described it as a 'quasi-academic think tank'. He told me he had been asked to keep an eye out for potential candidates. If I was interested, he would pass on my curriculum vitae.

Though I devoured the novels of Graham Greene and John le Carré, I had never contemplated a career in intelligence. Not in my wildest dreams. But what did I have to lose? It was a new and prestigious organisation that reported directly to the prime minister. It was bound to be interesting.

After several interviews and rigorous security checking, I was granted a Top Secret security clearance and went to work as a strategic analyst. Who would have believed it? A migrant with such a confusing background; Australia really was the land of opportunity! During my induction, I was warned about hostile intelligence services and made to understand that travel to the Soviet Union, China or other Eastern bloc countries was practically out of the question. It was not something I was contemplating in any case.

This was the start of my twelve-year career with the Australian government. After four years in intelligence, I moved to diplomacy, with policy assignments in Canberra, a term as ministerial adviser and a senior posting to the embassy in Bangkok. It was here that I became involved in the Australian peace initiative for Cambodia in the early 1990s. Cambodia and its people captured my heart and my imagination. By 1992, I had moved to the private sector and was heading up the Cambodian operations of Australia's national telecommunications company, Telstra, in Phnom Penh, just as the reconstruction of the war-ravaged country was getting underway.

In July 1992, I managed to escape Cambodia briefly for a long-planned holiday in Moscow with my friends, Olga and Bradley Wynne, where Olga was in the final year of her posting at the Australian embassy.

I had in fact been to Moscow once before in late 1987, during a brief stint as a foreign affairs journalist. At that time, President Mikhail Gorbachev was still trying to reform the Soviet Union within the parameters of a Communist system and his new buzz words, perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness), were on every-body's lips.

By the early 1990s, everything had been turned on its head. Though he survived a coup by Communist Party hardliners, Gorbachev was no longer leader. Boris Yeltsin, Gorbachev's radical reform rival who had rallied opposition against the coup, was now the first elected president of the Russian Federation. The red Communist flag with hammer and sickle had been replaced by the old Russian white, blue and red minus the Tsarist double-headed eagle. The final curtain had descended on the Soviet Union.

#