— he had lived

for many years in Southern Russia, and at the beginning

of that war he was appointed Chief Intelligence Officer

to the British forces, owing to his thorough knowledge

of the Crimea and of the Russian language. After the

war he was made British Consul of the Crimea, and

while there married my mother, who was the daughter

of the Admiral of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

— he had lived

for many years in Southern Russia, and at the beginning

of that war he was appointed Chief Intelligence Officer

to the British forces, owing to his thorough knowledge

of the Crimea and of the Russian language. After the

war he was made British Consul of the Crimea, and

while there married my mother, who was the daughter

of the Admiral of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

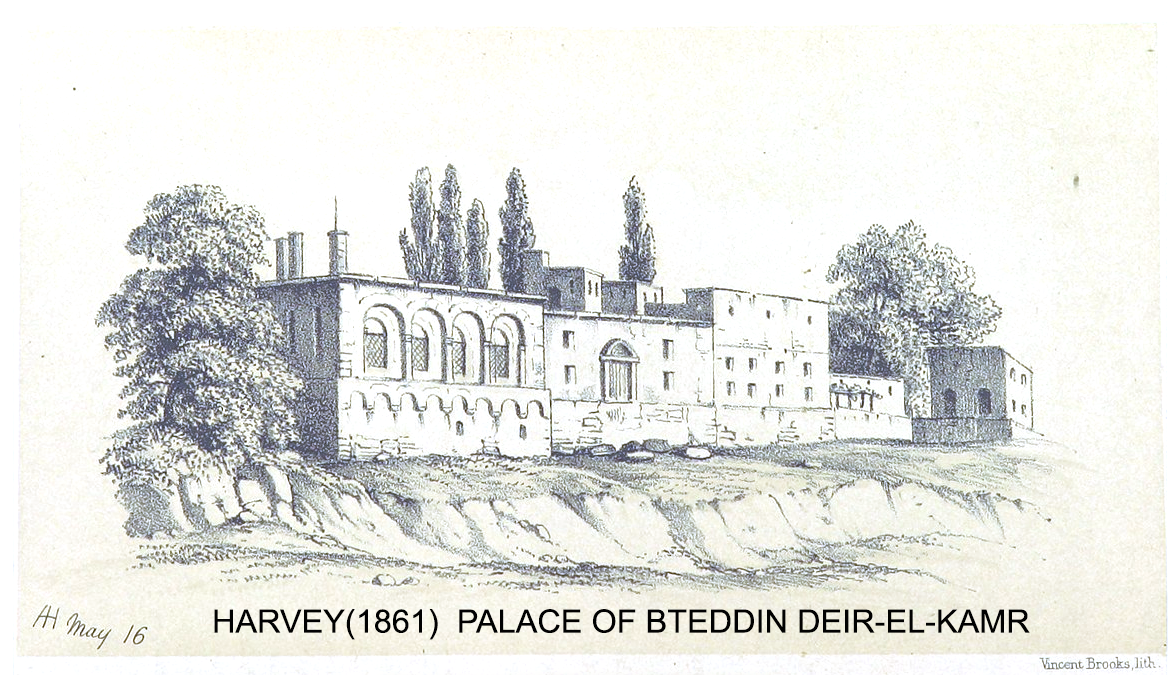

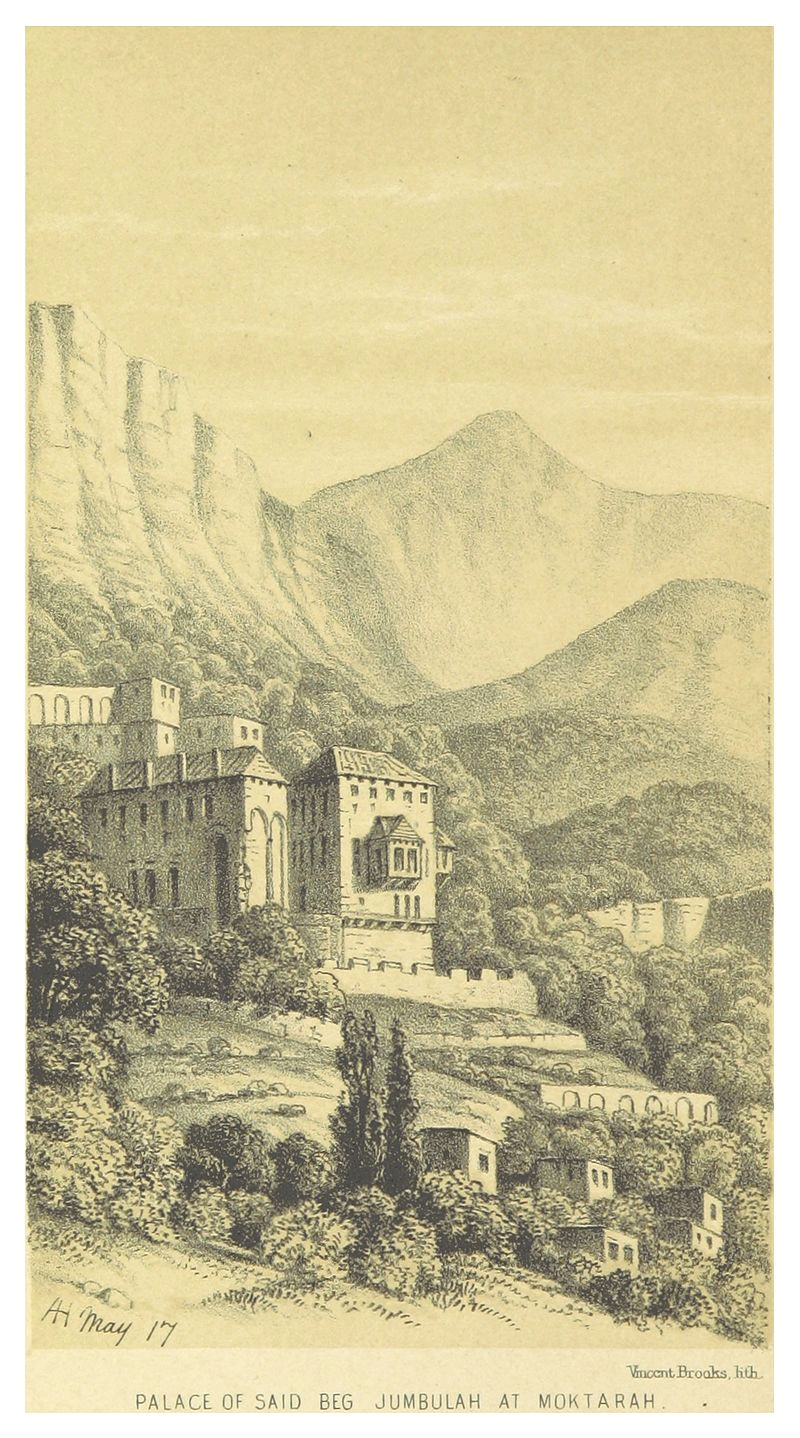

From Bteddin we would go on to Mukhtara and visit

the Druse Princes in their palace, surrounded by

magnificent gardens. In front of the palace there was

a large meidan or parade ground, where the game of

jreed is played. This is something like the game called

" Baiting the tiger." The druses play jreed riding on

their magnificent horses, using an oak staff instead of

a spear. Their horsemanship is wonderful and they

are able to dodge a staff hurled at them while going

at full gallop.

From Bteddin we would go on to Mukhtara and visit

the Druse Princes in their palace, surrounded by

magnificent gardens. In front of the palace there was

a large meidan or parade ground, where the game of

jreed is played. This is something like the game called

" Baiting the tiger." The druses play jreed riding on

their magnificent horses, using an oak staff instead of

a spear. Their horsemanship is wonderful and they

are able to dodge a staff hurled at them while going

at full gallop. [click]

[click]