A SONG OF SALVATION AT WEIHSIEN PRISON CAMP

By Mary Taylor PREVITE

August 25,1985

THEY WERE SPILLING from the guts of the low-flying plane, dangling from parachutes that looked like giant silk poppies, dropping into the fields outside the concentration camp. The Americans had come.

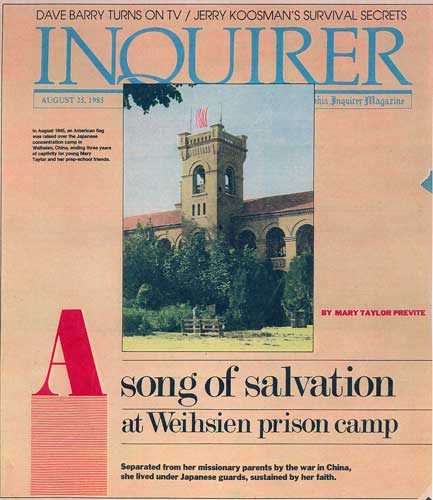

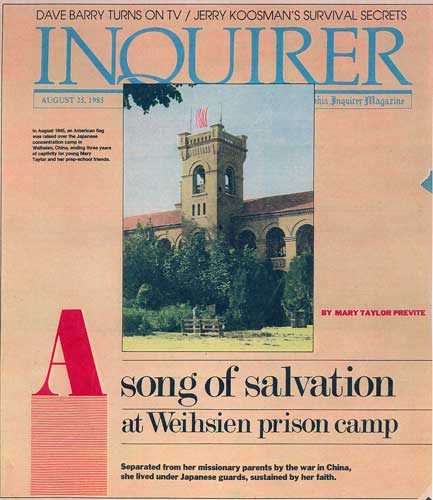

It was August 1945. "Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center," the Japanese called our concentration camp in China. I was 12 years old. For the past three years, my sister, two brothers and I had been captives of the Japanese. For 5½ years we had been separated from our parents by warring armies.

But now the Americans were spilling from the skies.

But now the Americans were spilling from the skies.

I raced for the forbidden gates, which were now awash with cheering, weeping, disbelieving prisoners, surging beyond those barrier walls into the open fields. Americans, British, men, women, children - dressed in proud patches and emaciated by hunger - we made a mad welcoming committee. Our Japanese guards put down their guns and let us go.

The war was over.

KATHLEEN, JAMIE, JOHNNY AND I were the children of Free Methodist missionaries. We and all our classmates and teachers had been taken prisoner in the early years of World War II when Japanese soldiers commandeered our boarding school in Chefoo, on the east coast of China. As the Japanese army advanced, my parents, James and Alice Taylor, escaped to China's vast Northwest, where, for the remainder of the war, they continued their missionary work.

Before the war came, the fabled land of my childhood was a country of ancient Buddhas, gentle temple bells and simple peasants harnessed to their plows. But across the China Sea, a clique of militarists was rising to power in Japan and pushing for expansion. They wanted "Asia for the Asians," with China, Manchuria and Japan cooperating under Japan's leadership.

They struck first in 1931 with an "incident" in Manchuria, and within six months they controlled it under a puppet government. Next, Japan started nibbling at China, eating her, as Churchill said, "like an artichoke, leaf by leaf." No Allied power was willing to use military force to stop the takeover.

As the Japanese continued to eat away at China, Dad and Mother were finding it increasingly difficult to continue their work in the Henan province in central China. The Japanese soldiers were cocky. When you pass through the city gate, you dismount and bow to us - that was the order. Twice, when Mother hadn't dismounted fast enough from her bicycle, soldiers struck her across the head with a stick.

So Dad and Mother took Johnny and me and headed for a breather in Chefoo, where the two older children, Kathleen and Jamie, were already enrolled in school.

The Chefoo School was, more than anything else, a British school. Its purpose was to serve the many children of Protestant missionaries in a vast, foreign continent - to be a tiny outpost where we could learn English and get a Western-style education. The original school had been 10 rooms and an outhouse, but by our time it had grown into a modern campus, a schoolmaster's dream, just a few steps off the beach.

When the Japanese army arrived in Chefoo, Latin master Gordon Martin was teaching a Latin noun to the Fourth Form. "So," he said softly, "here are our new rulers."

Wearing steel helmets, bemedaled khaki uniforms, highly polished knee-high boots, and carrying bayonets, Japanese soldiers took up duty on the road in front of the school. Swords swaggered at their waists.

From an aircraft carrier in the harbor, a plane dropped leaflets in Chinese explaining "The New Order in East Asia."

The Japanese Army is coming soon to protect Japanese civilians living in China. The Japanese Army is an army of strict discipline, protecting good citizens. Civil servants must seek to maintain peace and order. Members of the community must live together peacefully and happily. With the return of Japanese businessmen to China, the business will prosper once more. Every house must fly a Japanese flag to welcome the Japanese.

- Japanese Army Headquarters

There was no effective resistance. The New Order in Asia had arrived.

IT WAS THE SCHOOLTEACHER IN HER, I think, but Mother believed in learning things "by heart." And with so much turmoil around us - war, starvation, anxiety, distrust - she was determined to fill us with faith and trust in God's promises. The best. way to do this, she decided, was to put the Psalms to music and sing them with us every day. So with Japanese gunboats in the harbor in front of our house, and with guerrillas limping along Mule Road behind us, bloodied from their nighttime skirmishes with the invaders, we sang Mother's music from Psalm 91 at our family worship each morning:

"I will say of the Lord, He is my refuge and my fortress; my God, in Him will I trust....

"Thou shalt not be afraid for the terror by night....

"A thousand shall fall at thy side and ten thousand at thy right hand, but ... He shall give his angels charge over thee, to keep thee in all thy ways.... "

Our little choir soared with the music -

" ... to keep thee in all thy ways ....

Thou shalt not be afraid ....

We children had also sat wide-eyed in Sunday school, listening to spine-tingling stories of such pioneer missionaries as David Livingston in Africa, John G. Paton in the New Hebrides, and J. Hudson Taylor in China.

Hudson Taylor was my great-grandfather. At 21, he decided to give up his medical studies in England to pursue a dream - to take the Christian faith to every province of China. He sailed to China in 1853, and it was he who founded the Chefoo School in 1881.

He did not believe in public pleas for money or elaborate recruiting drives. He believed in God - and miraculous results.

"We do not expect God to send three million missionaries to China," Hudson Taylor had said, "but if He did, He would have ample means to sustain them all." Hudson Taylor founded the China Inland Mission, and God sent a thousand missionaries - and money to support them.

We Taylor children grew up on that kind of faith. Our father was the third generation of Taylors preaching in China. It seemed only natural to us when, in early 1940, Mother and Dad left us at the Chefoo School and returned far into China to continue their work. After all, it was China's war, Japan's war. England and America were neutral.

I was 7 years old at the time. My brother Johnny was 6.

ON THE MORNING OF DEC. 8, 1941, WE AWOKE to find Japanese soldiers stationed at every gate of our school. They had posted notices on the entrances: Under the control of the Naval Forces of Great Japan. Their Shinto priests took over our ballfield and performed some kind of rite and - just like that! - the whole school belonged to the Emperor.

There was reason enough for panic. The breakfast time radio reported the American fleet in flames at Pearl Harbor and two British battleships sunk off the coast of Malaya. When we opened the school doors, Japanese soldiers with fixed bayonets blocked the entrance. Our headmaster was locked in solitary confinement.

Throughout the month, Mr. Martin, the Latin master, had been preparing a puppet show for the school's Christmas program, and as far as he was concerned the war was not going to stop Christmas. Mr. Martin was like that. With his puppet dancing from its strings, he went walking about the compound, in and out among the children and the Japanese sentries.

And the Japanese laughed. They were human! The tension among the children eased after that, for who could be truly terrified of a sentry who could laugh at a puppet?

But with the anarchy of war, the Chinese beyond our gates were starving. Thieves often invaded the school compound at night, and, to our teachers' horror, one morning we came downstairs to find that all the girls' best overcoats had been stolen. After that, the schoolmasters took turns patrolling the grounds after dark, and our prep school principal, Miss Ailsa Carr, and another teacher, Miss Beatrice Stark, started sleeping with hockey sticks next to their beds.

MEANWHILE, IN FENGHSIANG, 700 miles away in northwest China, a Bible school student interrupted a faculty meeting and pushed a newspaper into my mother's hands. Giant Chinese characters screamed the headlines: Pearl Harbor attacked! U.S. enters war!

Mother was stunned. America at war! She had visions of the Japanese war machine gobbling her children - of Kathleen, Jamie, Mary and Johnny in the clutches of the advancing armies. She knew the stories of Japanese soldiers ravishing the women and girls during the Japanese march on Nanking. Numb with shock, she stumbled to the bedroom next door and fell across the bed. Wave after wave of her sobs shook the bed.

Then - it might have been a dream - she heard the voice of Pa Ferguson, her minister back in Wilkes Barre, Pa., speaking to her as he had when she was a teenager, saying: "Alice, if you look after the things that are dear to God, He will look after the things that are dear to you."

In later years, she told the story a hundred times.

"Peace settled around me," she said. "The terror was gone. We had an agreement, God and I: I would look after the things that were dear to God, and He would look after the things that were dear to me. I could rest on that promise."

In the years to come, she said, as Japanese bombs fell around them and as armies marched and mail trickled almost to nothing, "I knew that God had my children sheltered in His hand."

I REMEMBER SO WELL WHEN THE JAPANESE came and marched us away from our school. By then, the war had made us enemy aliens. Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaya had fallen to Japan. Burma had collapsed, and U.S. Maj. Gen. Joseph Stillwell put it bluntly: "We got a hell of a beating."

The Philippines had toppled.

It was November 1942. Wearing olive uniforms, the Japanese soldiers led us off to our first concentration camp, three miles across town. A straggling line of perhaps 200 children, proper Victorian teachers and God-fearing missionaries, we went marching into the unknown, singing from the Psalms. "God is our refuge and strength. .. therefore we will not fear...."

We had become prisoners of war.

We all had to wear armbands in those early days of the war: "A" for American, "B" for British. When our teachers and the Japanese weren't looking, the American children turned the "A" upside down, chalked out the crossbar and proudly wore a "V."

We were crammed into the camp like sardines. There were four family-size houses, each one bulging with 60 to 70 people. Ten months it was like this. We always sang to keep our spirits up:

We might have been shipped to Timbuktu.

We might have been shipped to Kalamazoo.

It's not repatriation,

Nor is it yet stagnation

It's only con-cen-tration in Chefoo.

We would hit the high note at the end and giggle.

To supplement the dwindling food supply, one of the servants from the old Chefoo School smuggled two piglets and some chicks over the wall for us to raise. For the first few nights, we hid the piglets under the veranda and fed them aspirin to keep them quiet. When the Japanese finally discovered them, they accepted them rather affectionately as our pets.

In the daytime, propped up on our steamer trunks, we practiced our English lessons, writing iambic quatrains about life in concentration camp:

Augustus was a pig we had,

Our garbage he did eat.

At Christmastime we all felt sad;

He was our Christmas treat.

After 10 months, they stacked us like cords of wood in the hold of a ship and brought us to the Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center, a larger concentration camp across the Shandong peninsula. This camp contained about 1,400 prisoners, mostly British and European, including some other children from Tientsin, Peking and elsewhere.

IN A PRISON CAMP, HOW DO YOU ARM YOURSELF against fear? Our teachers' answer was to fashion a protective womb around our psyches, insulating and cushioning us with familiar routines, daily school and work details.

Structure. Structure. Structure.

Our teachers taught us exactly what to expect. They marched us off to breakfast for a splash of steaming gao hang gruel (animal feed, even by Chinese standards). They trooped us back to our dormitory, mug and spoon in hand, to scrub the floor. We grouped for morning prayers, and sang:

God is still on the throne;

And He will remember His own ...

His promise is true;

He will not forget you.

God is still on the throne.

We lined up for inspection. Were we clean? Were we neat? Did we have our mending done? We settled down on our steamer-trunk beds for school: English, Latin, French, history, Bible. School must go on.

Structure. It was our security blanket.

One of the predictable routines of the camp was daily roll call. The ringing of the assembly bell would summon us to our assigned roll-call "district. " Then would come the strict lineups, with our prisoner numbers pinned to our chests, and the numbering off when the uniformed guards counted us, and then the delays while the guards tallied the totals from all six roll-call districts. And finally, the all-clear bell.

To the Japanese soldiers who missed their own families, our district, with more than 100 children, was their pride and joy. And when visiting Japanese officials monitored the camp, our roll call was the highlight of the show - little foreign. devils with prepschool manners, standing with eyes front, spines stiff at attention, numbering off in Japanese: Ichi ... nee .. . san...she...go....

Delays to the all-clear bell often dragged on and on. In summer we wilted in the insufferable heat; in winter we froze in the snow. But the innocence of children turns even the routines of war into games. While the Japanese tallied the prisoner count, we played marbles, or leapfrog, or practiced semaphore and Morse Code for our Brownie, Girl Guide and Boy Scout badges.

THE WEIHSIEN CONCENTRATION camp had once been a well-equipped Presbyterian mission compound, complete with a school of four or five large buildings, a hospital, a church, three kitchens, a bakery and rows of endless rooms for resident students. Many years before, novelist Pearl Buck had been born there, and so had Time and Life publisher Henry Luce.

The compound stretched only 200 yards at its widest point and was 150 yards long. Though the buildings themselves were intact, everything else was a shambles, wrecked by how many garrisons of Chinese, then Japanese, soldiers. Now, with 1,400 prisoners, it was hopelessly overpopulated.

In the dormitories, only 18 inches separated one bed from the next. Your snore, your belch, the nightly tinkle of your urine in the pot, became your neighbor's music. For adults, this lack of privacy was the worst hell.

The grownups in the camp knew enough about war to be afraid. Indeed, a few came to Weihsien with the baggage of hate from earlier Japanese prisons. But I saw the war through the eyes of a child, as an endless pajama party, an endless campout. I entrusted my anxieties to our teachers in the belief that they would take care of us. Or if they couldn't, God would.

Our spirits could scamper to the heavens atop the hundreds and hundreds of God's promises, such as: "All things work together for good to them that love God."

We could tell endless stories about God's rescuing His people: Moses leading God's children out of slavery into their Promised Land. The ravens' feeding the hungry prophet Elijah in the wilderness. God's closing the mouths of the lions to protect Daniel in the Lions Den.

You could breathe the anticipation: God was going to add our very own story to the Miracles of the Ages.

"I was not afraid of our Japanese guards or of being interned," our prep-school headmistress, Miss Ailsa Carr, would write me years later. "There was no sense in taking thought for the future, for there was nothing we could do about it anyway. Occasionally, I faced the end - whichever way it went - as being forced to dig a trench and then being lined up and machine-gunned into it, and prayed that my turn might come near the beginning."

I thought about it once when I was young, how curious it was that children watching enemy bayonet drills at dusk could know no fear.

What I did fear, though, were the guards' Alsatian police dogs. Forty years have not dimmed the terror of one screaming night. Victoria was only a tiny ball of fur. Sometimes, under my bedcovers after dark, she would purr and suck on my finger as if it were a nipple. I wondered whether mothers felt warm and soft like that. Along with the "remember-me-forever" signatures and the fingerprints of all my 11 dorm mates, I had Victoria's paw print. I have it still. Victoria Frisky Snowball ---- Miss Broomhall's kitten. Miss Broomhall was our headmistress.

I hated the dogs. You could play with the Japanese guards but never with their dogs. The dogs were trained to kill.

Tucked under my mosquito net, I listened to the nighttime sounds from the roll-call field below our window. I heard the tread of footsteps - one of the Catholic priests, perhaps, pacing in his nightly meditation. Then I heard the coarse crunch of gravel - I knew that sound - rough leather boots of the Japanese soldier on his night patrol. His police dog would be with him, I knew. How, I wondered, does he get to be friends with a killer dog?

Suddenly, below our window, a terrified, yowling shriek ripped the stillness, clashing in a hideous duet with a guttural barking muffled by the tiny ball of fur between those bloody teeth. My little body froze, and my throat retched on a voiceless scream. Perhaps my dorm mates ran for the window. I do not know. I buried my head in terror and stuffed the pillow around my ears.

They cleaned the mess by morning - perhaps our teachers, perhaps our older brothers. But we knew. Miss Broomhall, always sensible and very proper, walked a little slower after that.

SELF-GOVERNMENT AT WEIHSIEN  ruled that every able-bodied person should work. The prisoners did everything - cooked, baked, swabbed latrines. My older sister, Kathleen, scrubbed clothes. Jamie pumped long shifts at the water tower and carried garbage. John made coal balls. Before and after school, I mopped my square of floor, mended clothes, stoked the fire, and carried coal dust. Not coal. The Japanese issued only coal dust.

ruled that every able-bodied person should work. The prisoners did everything - cooked, baked, swabbed latrines. My older sister, Kathleen, scrubbed clothes. Jamie pumped long shifts at the water tower and carried garbage. John made coal balls. Before and after school, I mopped my square of floor, mended clothes, stoked the fire, and carried coal dust. Not coal. The Japanese issued only coal dust.

Like every other Weihsien problem, coal dust had its dark side and its bright side. You could take your pick. You could grump yourself miserable about having only coal dust to burn; or, when you were breaking the ice in the water bucket in the morning to wash your face, you could count your blessings that you had anything at all to fuel the stove.

We younger girls made a game of carrying the coal buckets. In a long human chain - girl, bucket, girl, bucket, girl, bucket, girl - we hauled the coal dust from the Japanese quarters of the camp back to our dormitory, chanting all the way, "Many hands make light work." Then, in the biting cold, with frostcracked fingers, we shaped coal balls out of coal dust and clay - two shovels of coal dust, one shovel of clay and a few splashes of water. Grown-ups swapped coal ball recipes. Winter sunshine made the coal balls dry enough for burning.

One person in the camp who didn't work at a job was Grandpa Taylor. Almost 80, and the only surviving son of J. Hudson Taylor, he had dwindled away to less than 80 pounds. His clothes bagged around his emaciated frame. "Grandpa Taylor," people begged him, "let us take in your clothes to make them fit."

He always smiled, his face haloed with glory: "God is going to bring me out of Weihsien," he used to say. "And I'm going to fit in these clothes again." (He was right: he did survive the war and was flown back to England.)

The grown-ups said Grandpa looked as though he had one foot on Earth and the other in heaven. I snuggled up next to him on his bed and ran my little fingers through the crinkly silk of his snow-white beard to feel the cauterized scar on his cheek where a rabid dog had bitten him in his early days in China. Of all the children in the Chefoo School we Taylors were the, only ones to have a grandpa in the camp.

Why do I remember Weihsien with such tender memories?

Say "concentration camp" to most people, and you bring forth visions of gas chambers. death marches, prisoners branded and tattooed like cattle. Auschwitz. Dachau. Bataan.

Weihsien was none of that.

Awash in a cesspool of every kind of misery, Weihsien was, nonetheless, for us, a series of daily triumphs - earthy victories over bedbugs and rats and flies. If' you have bedbugs, you launch the Battle of the Bedbugs each Saturday. With knife or thumbnail, you attack each seam of your blanket or pillow, killing all the bugs and eggs in your path.

If you run out of school notebooks, you erase and use the old ones again - and again - until you rub holes through the paper.

If you panic at the summer's plague of flies, you organize the schoolchildren into competing teams of fly-killers. My younger brother John - with 3,500 neatly counted flies in his bottle - won the top prize, a can of Rose Mille pate, food sent by the Red Cross.

If you shudder at the rats scampering over you at night, you set up a Rat Catching Competition, with concentration camp Pied Pipers clubbing rats, trapping rats, drowning them in basins, throwing them into the bakery fire. Our Chefoo School won that contest, too, with Norman Cliff and his team bringing in 68 dead rats - 30 on the last day. Oh, glorious victory! The nearest competitor had only 56.

One, two, three, four, five years I hadn't seen Daddy. I could hardly remember his face now, but I could still hear his voice: "Mary Sweetheart" - he always called me Mary Sweetheart - "there's a saying in our family: A Taylor never says `I can't.' "

In the far reaches of my mind, like a needle stuck on a gramophone record, I heard the messages playing:

A Taylor never says "I can't.

Thou shalt not be afraid....

SOMEWHERE OUT THERE, THE WAR dragged on. Midway. Guadalcanal. Eniwetok. Saipan, where more than 40,000 were killed or wounded in one battle. Forty million people would die before the madness ended.

But inside our prison walls, we preserved the wonders of childhood. From the third-floor window of his dormitory, Jamie perched in a hollow tree trunk behind a rain gutter and watched a family of sparrows nesting and raising their young. If he did it right, he could chew up bread saved from Kitchen Number One and get the fledgling sparrows to eat the mush right out of the side of his mouth.

There were also sports. If the food supply is dwindling and starvation is near, should you expend your energy on sports? In other Japanese prison camps in Shanghai and in Hong Kong, doctors advised against games and exercise because prisoners had no energy to spare. But Weihsien was different. Nourishing the spirit was as important as feeding the body. So on any weekend after school, we children played basketball or rounders, hockey or soccer. The man who organized these games was Olympic gold medal winner Eric Liddell - Uncle Eric, we called him. The Flying Scotsman.

Almost everyone in camp had heard of Eric Liddell. The folklore about him seemed almost bigger than life. In later years, the film Chariots of Fire would dramatize the accomplishments of this man who refused to run in the Olympics on Sunday because of his religion. But Uncle Eric wasn't a Big Deal type; he never sought the spotlight. Instead, he made his niche by doing little things other people hardly noticed. You had to do a lot of imagining to think that Liddell had grabbed world headlines almost 20 years earlier, an international star in track and rugby.

When we had a hockey stick that needed mending, Uncle Eric would truss it almost as good as new with strips ripped from his sheets. When the teenagers got bored with the deadening monotony of prison life and turned for relief to the temptations of clandestine sex, he and some missionary teachers organized an evening game room. When the Tientsin boys and girls were struggling with their schoolwork, Uncle Eric coached them in science. And when Kitchen Number One competed in races in the inter-kitchen rivalry, well, who could lose with Eric Liddell on our team?

One snowy February day in 1945, Liddell died of an inoperable brain tumor. The camp was stunned. Through an honor guard of solemn schoolchildren, his friends carried his coffin to the tiny cemetery in the corner of the Japanese quarters. There, a little bit of Scotland was tucked sadly away in Chinese soil.

FOR A CHILD WHO USED TO HAVE to be bribed to eat a bite of food, eating the concentration camp fare was no problem at all. I was hungry! In the early days of the war, we lived on gao Bang, the roughest broom corn, or lu dou beans cooked into hot cereal for breakfast, and all the bread we wanted. Lunch was always stew, stew, stew. "S.O.S.," we called it: Same Old Stew. Supper was more leftover stew - watered down to soup.

Only the stouthearted could work in the butchery with the maggot-ridden carcasses. Plagues of flies laid eggs on the meat faster than the team could wipe them off. When the most revolting-looking liver - horribly dark, with a hard, cream-colored edge - arrived with the day's food supplies, the cooks called in our school doctor for a second opinion. Was it fit to eat? Probably an old mule, he guessed. So we ate it.

If you wanted to see the worst in people, you stood and watched the food line, where griping and surliness were a way of life. Hungry prisoners were likely to pounce on the food servers, who were constantly being accused of dishing out more or less than the prescribed half dipper or full dipper of soup. It was a no-win job.

Having been taught self-control, we Chefoo children watched the cat fights with righteous fascination. Shrieking women in the dishwashing queue hurled basins of greasy dishwater at each other. Fights were common. But not among the Chefoo contingent.

Our teachers insisted on good manners. There is no such thing, they said, as one set of manners for the outside world and another set for a concentration camp. You could be eating the most awful-looking glop out of a tin can or a soap dish, but you were to be as refined as the two princesses in Buckingham Palace.

Sit up straight. Don't stuff food in your mouth. Don't talk with your mouth full. Don't lick your knife. Spoon your soup toward the back of the bowl, not toward the front. Keep your voice down. Don't complain.

Food supplies dwindled as the war dragged on. If you wanted to be optimistic, you could guess that the Allies were winning and that you were going hungry because the Japanese weren't about to share their army's dwindling food with Allied prisoners. Grown men shrank to 100 pounds. But our teachers shielded us from the debates among the camp cynics over which would come first, starvation or liberation.

By 1944, American B-29 Superfortresses from bases in Calcutta, China and the Marianas were bombing Japan. There were many meatless days. When even the gao hang and lu dou beans ran out, the cooks invented bread porridge. They soaked stale bread overnight, squeezed out the water and mixed up the mush with several pounds of flour seasoned with cinnamon and saccharin. Only our hunger made it edible.

An average man needs about 4,800 calories a day to fuel heavy labor, about 3,600 calories for ordinary work. Camp doctors guessed that the daily food ration for men in our camp was down to 1,200 calories. Although no one said so out loud, the prisoners were slowly starving. The signs were obvious - emaciation, exhaustion, apathy. Some prisoners had lost more than 100 pounds. Children had teeth growing in without enamel. Adolescent girls were growing up without menstruating.

That's when our teachers discovered egg shell as a calcium supplement to our dwindling diet. On the advice of the camp doctors, they washed and baked and ground the shells into a gritty powder and spooned it into our spluttering mouths each day in the dormitory. We gagged and choked and exhaled, hoping the grit would blow away before we had to swallow. But it never did. So we gnashed our teeth on the powdered shells - pure calcium.

Still, there was a gentleness about these steely teachers. On my birthday, my teacher created a celebration - with an apple - just for me. The apple itself wasn't so important as the delicious feeling that I had a "mother" all to myself in a private celebration - just my teacher and me - behind the hospital.

In the cutting of wondrously thin, translucent apple circles, she showed me that I could find the shape of an apple blossom. It was pure magic. On a tiny tin-can stove fueled by twigs, she fried the apple slices for me in a moment of wonder. Even now, after 40 years, I still look for the apple blossom hidden in apple circles. No birthday cake has ever inspired such joy.

It was a lasting gift these teachers gave us, preserving our childhood in the midst of bloody war. But if we children filled our days with childish delights, our older brothers and sisters had typically adolescent worries: college, jobs, marriage. Kathleen, quite head-over-heels in love by now, was sporting a lovely page-boy coif with a poof of hair piled modishly over her forehead.

"God has forgotten all about us," one of her friends moaned one day. "We're never going to get out of here. And we're never going to get husbands." With malnutrition slowing down my hormones, no such foolishness entered my mind.

WE LISTENED WIDE-EYED TO THE whisper that passed from mouth to mouth one day at roll call: "Hummel and Tipton have escaped!"

My heart pounded against my ribs as I grabbed Podgey Edwards and started jumping up and down. I tried to recall what Hummel and Tipton looked like. Shaved bald and tanned brown like Chinese, someone said. Chinese clothes. But how in the world, I wondered, did they get over the electrified wire atop the camp wall without getting killed?

Our teachers and the older boys were more subdued. Escape would mean instant reprisals.

Roll call that day dragged on and on. With Hummel and Tipton missing, the guards' count failed to tally, and when the Japanese realized what was wrong the commandant unleashed the police dogs. And Japanese soldiers promptly arrested the nine remaining roommates from the bachelor dormitory and locked them up in the church for days of ugly interrogation. But nothing worked. Hummel and Tipton were gone.

Roll call was never the same after that. Instead of one, we now had two roll calls a day. Japanese guards cursed and shouted. They counted and recounted us each time. They also dug a monstrous trench beyond the wall, 10 feet deep and five feet wide, and beyond that they strung a tangle of electrified wire. No one would ever escape again.

Laurance Tipton had been an executive with a British tobacco importing firm. Arthur Hummel Jr. had been a professor of English at Peking's Catholic University; today, he is the U.S. ambassador to China.

Not until years later did I learn the story of their escape. Shortly after the nightly changing of the guards, in a prearranged plan with Chinese guerrillas, they had gone over the wall at a guard tower. For the rest of the war, maneuvering in the hills within 50 miles of Weihsien, they employed Chinese coolies - either repairmen or "honey-pot men" who carried out the nightsoil from our latrines and cesspools - to smuggle coded messages in and out of the camp.

This was our "bamboo radio," known only to the camp's inner circle. It was a deathly dangerous business. The Japanese had once found a concealed letter on a Chinese coolie as they were checking him before entrance into the camp; they dragged him into the guardhouse and beat him until he was unconscious. He was never seen again. Another Chinese confederate who was passing black-market supplies over the wall to hungry prisoners slipped, in his hurry to get away as the guards approached, and was electrocuted on the wire that crisscrossed the wall. The Japanese left his body hanging there for most of the day, as a grim warning.

News from the "bamboo radio" was delivered, therefore, with extreme care. A message would be written on the sheerest silk, wadded into a pellet, placed inside a contraceptive rubber and then stuffed up the nose or inside the mouth of a Chinese workman. Once inside the camp, at a prearranged spot, the coolie would clear his sinuses and spit out the news. Insiders then pounced on the spit wad and took it to the translator.

Ironically, the Japanese themselves helped confirm the accuracy of some of the smuggled information. They distributed English editions of the Peking Chronicle, a carefully doctored propaganda rag filled with hideous lists of sunken Allied ships and downed American planes. In our Current Events class, we followed the names of the places where battles were in progress: the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, Guadalcanal, Kwajalein, Guam, Manila, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. It was obvious where the battles were raging: closer and closer to Japan! Our bamboo radio was right. Japan was on the run.

For some of the adults, the prospect of Allied victory was tinged with terror. If the Japanese knew they faced defeat, what would they do to us? Does a defeated army rape and kill its prisoners? Would it hold us hostage to prevent more bombings of Japan? Those were some of the unvoiced agonies of the adults.

We children ached, instead, for the Japanese guards who had become our friends. Hara-kiri, someone told us, was the honorable way for a Japanese soldier to face defeat. Ceremonial suicide. The Chefoo boys who knew about these things demonstrated on their bellies where the cuts of the samurai sword would be made - a triangle of self-inflicted wounds, followed by a final thrust to the heart. I shuddered. The Japanese guard who lifted us girls up so gently into his guard tower and dropped us for delicious moments of freedom into the field beyond the wall - would he commit hara-kiri?

NONE OF THESE CONSIDERATIONS, our teachers said, was to interfere with school. The Chefoo School had been called "the best English-speaking school east of the Suez," and our teachers had no intention of dropping the standards now. In times of peace, the Sixth Form (roughly equivalent to the senior year in an American high school) boys and girls crammed each year for their Oxford matriculation exams. From these, a passing grade would open the doors to universities in England. And jobs.

Nothing will change, our teachers said. You will go to school each day. You will study. You will take your Oxfords. You will pass.

Sitting on mattresses in the dormitory, we conjugated Latin verbs with Mr. Martin. In summer heat, we studied Virgil and Bible history and French under the trees. Between roll calls, scrubbing laundry, scouring latrines, hauling garbage and stoking kitchen fires, the Sixth Form boys and girls crammed for their Oxford exams.

In the blistering August heat of 1943, 11 students sweltered through the test, and 11 passed. The next year, Kathleen and her 13 classmates took the exams. They all passed. The year after that, 11 more sat for the exam. Nine passed. And when the war was over, Oxford University confirmed the results.

The missionary and education community of northern China in those days was a remarkable collection of talent. Besides teaching the young, the internees organized adult education classes on topics that ranged from bookkeeping to woodworking to the study of such languages as Chinese, Japanese, Mongolian and Russian. They could also hear lectures on art or sailing or history, and they could attend lively evening discussions on science and religion, where agnostics debated Roman Catholics and Protestants about creation, miracles and the Resurrection.

On Sundays there were early-morning Catholic masses, then Anglican services at 11 a.m., then holiness groups, Union Church, and Sunday-night singspiration. We also worshiped in glorious Easter sunrise services.

Weihsien was a society of extraordinary complexity. It had a hospital, a lab and a diet kitchen. It had its own softball league, with the Tientsin Tigers, the Peking Panthers and the Priests' Padres playing almost every summer evening. Though we young ones never knew it, Weihsien also had its prostitutes, alcoholics, drug addicts, roving bands of bored adolescents, and scroungers and thieves who filched extra food from the kitchens and stole coal balls left to bake in the sun.

Weihsien was a society of extraordinary complexity. It had a hospital, a lab and a diet kitchen. It had its own softball league, with the Tientsin Tigers, the Peking Panthers and the Priests' Padres playing almost every summer evening. Though we young ones never knew it, Weihsien also had its prostitutes, alcoholics, drug addicts, roving bands of bored adolescents, and scroungers and thieves who filched extra food from the kitchens and stole coal balls left to bake in the sun.

Compressed into that 150-by-200-yard compound were all the shames and glories of a modern city.

Including music. Someone found a battered piano moldering in the church basement and made it the centerpiece of a 22-piece symphonette. It was a glorious combination - brass by the Salvation Army band, woodwinds by the Tientsin Dance Band, and violins and cellos by assorted private citizens.

There was also a choral society that sang classical songs and madrigals - Handel's The Messiah, Mendelssohn's Elijah and Stainer's The Crucifixion. And yet another group of prisoners organized a sophisticated drama society, whose ultimate triumph was its production of George Bernard Shaw's Androcles and the Lion. To costume 10 Roman guards with armor and helmets, stage hands soldered together tin cans from the Red Cross food parcels.

The church was always jammed for these performances. It was our escape from the police dogs, barbed wire barriers, stinking latrines and gnawing hunger.

SOME OF US CHILDREN HAD GROWN more than a foot since our parents first sent us off to Chefoo School. Providing clothes for a school full of growing children was going to take a giant miracle. But hadn't the Lord promised: "If God so clothe the grass of the field, shall He not much more clothe you?"

Clothes and shoes for us little ones was easy. We grew into hand-me-downs. We patched and then patched the patches. But clothing the older boys posed a serious problem: They were facing the third winter of the war - with no winter trousers - until Mrs. Lack had her dream. In the dream, she was going from mattress to mattress looking for dark blankets that could be made into winter slacks. Blankets for trousers. Of course! Why hadn't they thought of it before?

In the dinner queue - where hunger heightened contentiousness - the skeptics started in on Mrs. Lack.

"Trousers out of blankets?"

"Blankets, my dear, aren't made of woven fabric. The seats will be out the first time the boys sit down."

How could they understand that if God had told her to make trousers out of blankets, He would make it His business to keep the seats in?

But just then, a kindly old stranger interrupted. "I used to be a tailor in Tientsin," he told Mrs. Lack. "I'm old and not much good these days, but maybe I could help you cut them out."

By early December, when the thermometer dipped to 17 degrees, the trousers - hand-tailored - were ready. Temperatures reached 3 below zero that winter. At the end of April, when the last snows were melting, the first boy came to Mrs. Lack.

"May I wear my khaki shorts now?" he asked. "It's still a bit cold now, isn't it?"

"But the seat is splitting in my trousers," he said with an uncomfortable blush.

After five winter months, the first seat had given way.

WE WOULD WIN THE WAR, OF COURSE, AND when we did, we would need a Victory March. So on Tuesday evenings - all so clandestinely, in a small room next to the shoe repair shop - the Salvation Army band practiced a newly created Victory Medley. It was a joyful mix of all the Allied national anthems. Because the Japanese were suspicious of this "army" with its officers, uniforms and military regalia, the Salvation Army in China had changed its Chinese name from "Save the World Army" to "Save the World Church."

The Salvation Army had guts. Right under the noses of the Japanese - omitting the melodies so the authorities wouldn't recognize the tunes - Brig. Stranks and his 15 brass instruments practiced their parts of the victory medley each week, sandwiching it between triumphant hymns of the church - "Onward, Christian Soldiers," "Rise Up, 0 Men of God" and "Battle Hymn of the Republic." We would be ready for any victor - American, English, Chinese, Russian - or God. And victory would surely come.

In May of 1945 the war was escalating to some kind of climax.

In the darkness, I sat bolt upright in my bed. Off in the distance the bell in the bell tower atop Block 23 was ringing. Within moments the camp was in pandemonium. On the roll-call field, angry Japanese voices shouted a staccato of commands. It was clear that they hadn't rung the bell. What could it mean, a bell tolling at midnight? An escape signal? A victory signal?

Numb with sleep and dressed in pajamas, we stumbled outside to the roll-call field where an angry soldier, pistol drawn, barked lineup orders at us in the darkness. The Japanese counted us and counted us again. They demanded explanations. They were particularly angry, we found out later, because the bell was their prearranged alarm to call in the Japanese army in case we prisoners reacted with a disturbance that night. It was 1 o'clock before they finished the head counts and sent us back to bed, but by then, the rumor of what had happened filtered through the ranks. The Germans had surrendered! Our "bamboo radio" had brought the news. The war in Europe was over.

Months before, on a dare, two of the prisoners had made a pact that when the Allies trounced the Germans, they would ring the tower bell at midnight.

The camp was delirious with hope. We had licked the Germans, and we were going to lick the Japanese. One month? Two months? Three months more? We dreamed and conjured up visions of The End.

IT WAS FRIDAY, AUG. 17, 1945. A SCORCHING heat wave had forced the teachers to cancel classes, and I was withering with diarrhea, confined to my mattress atop three steamer trunks in the second-floor hospital dormitory.

Rumors were sweeping through the camp like wildfire. The prisoners were breathless with excitement - and some with terror. Although we knew nothing of the atomic bomb, the bamboo radio had brought the news two days ago that Japan had surrendered.

Was it true?

Mr. Izu, the Japanese commandant, was tightlipped, refusing to answer questions.

Lying on my mattress in mid-morning, I heard the drone of an airplane far above the camp. Racing to the window, I watched it sweep lower, slowly lower, and then circle again. It was a giant plane, and it was emblazoned with an American flag. Americans were waving at us from the windows of the plane!

Beyond the treetops, its silver belly opened, and I gaped in wonder as giant parachutes drifted slowly to the ground.

Weihsien went mad.

Oh, glorious -cure for diarrhea! I raced for the entry gates and was swept off my feet by the pandemonium. Prisoners ran in circles and pounded the skies with their fists. They wept, cursed, hugged, danced. They cheered themselves hoarse. Wave after wave of prisoners swept me past the guards and into the fields beyond the camp.

A mile away we found them - seven young American paratroopers - standing with their weapons ready, surrounded by fields of ripening broom corn.

Advancing toward them came a tidal wave of prisoners, intoxicated with joy. Free in the open fields. Ragtag, barefoot, hollow with hunger. They hoisted the paratroopers' leader onto their shoulders and carried him back toward the camp in triumph.

In the distance, from a mound near the camp gate, the music of "Happy Days Are Here Again" drifted out into the fields. It was the Salvation Army band blasting its joyful Victory Medley. When they got to "The Star Spangled Banner," the crowd hushed.

0, say, does that star-spangled banner yet wave, o'er the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave?

From up on his throne of shoulders, the young, sun- bronzed American major struggled down to a standing salute. And up on the mound by the gate, one of the musicians in the band, a young American trombonist, crumpled to the ground and wept.

OVERNIGHT, OUR WORLD changed. Giant B-29s filled the skies each week, magnificent silver bombers opening their bellies and spilling out tons of supplies. While they provided us with desperately needed food, the B-29s were also a menace. Suspended from giant parachutes, monstrous oil drums crammed with canned food bombarded the fields around the camp. Once, a crate of Del Monte peaches crashed through the kitchen roof. Outside the walls, a falling container fractured the skull of a small Chinese boy.

Our teachers issued orders for us to run for the dormitories whenever we sighted bombers. They were not about to have us survive the war and then be killed by a shower of Spam.

One Saturday in September, as I was running for cover from the bombers, my dorm mate ran toward me, shouting, "Mary! Mary! You may be leaving on the next plane."

The following Monday, on the tiny landing strip beyond the camp, Kathleen, Jamie, Johnny and I boarded an Army transport plane. After being separated from Daddy and Mother for 5½ years, we were headed home.

We flew 600 miles into the interior, traveled 100 miles on a Chinese train, and found ourselves at last on an old-fashioned, springless mule cart for the final 10 miles of the trip, escorted now by a Chinese Christian friend. It was a rainy September day, and as the squealing wooden wheels of the cart sloshed a foot deep in the mud, it seemed to us that the journey would never end.

We finally decided to brave the world on our own, running ahead on foot while our escort, Mr. Soong, brought the baggage along after us in the mule cart. Chinese peasants in the fields along the road blinked in amazement at the four foreign devil children struggling through the mud. We were a soggy mess.

Along the lonely, mud clogged road the gao bang corn stood tall in the fields - the frequent hiding place for brigands and bandits to pounce on unwary travelers. Evening was coming, and off in the walled town of Fenghsiang, the giant city gates would be closing at dark - shutting for the night to protect the populace from bandits.

Kathleen and Jamie, who knew about these things, worried about the city gate. Would we reach Fenghsiang before it closed for the night? If so, would the gatekeeper break the rule and open it to strangers?

But on that night of miracles - Sept. 11 - at 8 o'clock, the city gate stood wide open as we approached. On we walked, through the gate and along the main street lined with packed mud walls. Without electricity, the town was black, the streets largely deserted.

Kathleen walked slowly toward a man who passed us in the darkness. "Would you take us to Rev. Taylor of the Christian Mission?" she asked in her most polite Chinese. The man muttered something and moved away. In China, no nice girl approaches a man. Neither does she walk in the street after dark.

Kathleen approached a second man. "Would you take us to Rev. Taylor of the Christian Mission?"

His eyes adjusted to the darkness as he looked at us. Four white children. "Yes. Oh, yes!" he said.

The man was a Bible school student of our parents, and he recognized at once that we were the Taylor children for whom the Bible school had prayed for so long. He was gripped by the drama of the situation.

Down the block, through the round moon gate and into the Bible school compound he led us, stumbling as we went. There, through a back window, I could see them - Daddy and Mother - sitting in a faculty meeting.

I began to scream. I saw Father look up.

At the front door, the student pushed ahead of us through the bamboo screen. "Mrs. Taylor," he said, "the children have arrived."

Caked with mud, we burst through the door into their arms - shouting, laughing, hugging - hysterical with joy. And the faculty meeting quietly melted away.

***

The author wishes to acknowledge her indebtedness to the following for supplementing her observations of life in the Weihsien concentration camp: Norman Cliff, author of Courtyard of the Happy Way (Arthur James Ltd.); Langdon Gilkey, author of Shantung Compound (Harper & Row); and Beatrice Lack, author of In Simple Trust (Overseas Missionary Fellowship Books)

MARY TAYLOR PREVITE is the administrator of the Camden County Youth Center in Blackwood, N.J.

But now the Americans were spilling from the skies.

But now the Americans were spilling from the skies.

ruled that every able-bodied person should work. The prisoners did everything - cooked, baked, swabbed latrines. My older sister, Kathleen, scrubbed clothes. Jamie pumped long shifts at the water tower and carried garbage. John made coal balls. Before and after school, I mopped my square of floor, mended clothes, stoked the fire, and carried coal dust. Not coal. The Japanese issued only coal dust.

ruled that every able-bodied person should work. The prisoners did everything - cooked, baked, swabbed latrines. My older sister, Kathleen, scrubbed clothes. Jamie pumped long shifts at the water tower and carried garbage. John made coal balls. Before and after school, I mopped my square of floor, mended clothes, stoked the fire, and carried coal dust. Not coal. The Japanese issued only coal dust. Weihsien was a society of extraordinary complexity. It had a hospital, a lab and a diet kitchen. It had its own softball league, with the Tientsin Tigers, the Peking Panthers and the Priests' Padres playing almost every summer evening. Though we young ones never knew it, Weihsien also had its prostitutes, alcoholics, drug addicts, roving bands of bored adolescents, and scroungers and thieves who filched extra food from the kitchens and stole coal balls left to bake in the sun.

Weihsien was a society of extraordinary complexity. It had a hospital, a lab and a diet kitchen. It had its own softball league, with the Tientsin Tigers, the Peking Panthers and the Priests' Padres playing almost every summer evening. Though we young ones never knew it, Weihsien also had its prostitutes, alcoholics, drug addicts, roving bands of bored adolescents, and scroungers and thieves who filched extra food from the kitchens and stole coal balls left to bake in the sun.