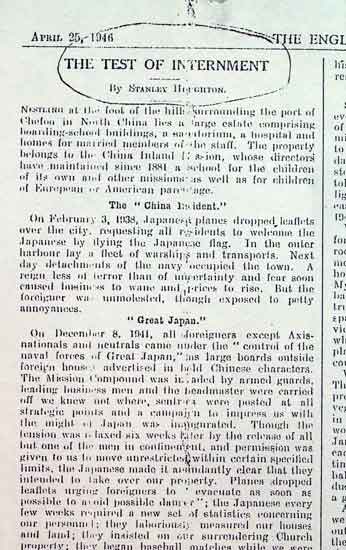

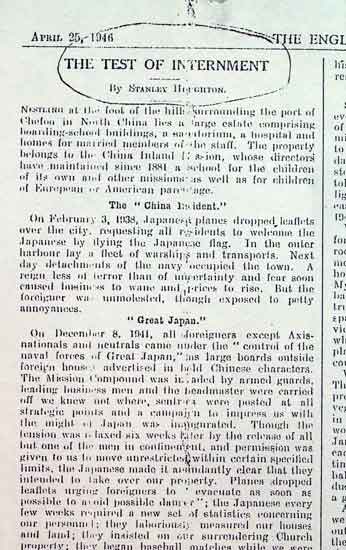

The Test Of Internment

By Stanley Houghton

THE ENGLISH CHURCHMAN AND ST. JAMES CHRONICLE

APRIL 25, 1946

Nestling at the foot of the hills surrounding the port of Chefoo in North China lies a large estate comprising boarding-school buildings, a sanatorium, a hospital and homes for married members of the staff. The property belongs to the China Inland Mission whose directors have maintained since 1881 a school for the children of its own and other missionaries as well as for children of European or American parentage.

The “China Incident”

On February 3, 1938 Japanese planes dropped leaflets over the city, requesting all residents to welcome the Japanese by flying the Japanese flag. In the outer harbour lay a fleet of warships and transports. Next day, detachments of the navy occupied the town. A reign less of terror than of uncertainty and fear soon cased businesses to wane and prices to rise. But the foreigner was unmolested, though exposed to petty annoyances.

“Great Japan”

On December 8, 1941, all foreigners except Axis-nationals and neutrals came under the control of the naval forces of “Great Japan,” as large boards outside foreign houses advertised in bold Chinese characters. The mission Compound was invaded by armed guards. Leading business men and the headmaster were carried off we knew not where, sentries were posted at all strategic points and a campaign to impress us with the might of Japan was inaugurated. Though the tension was relaxed six weeks later by the release of all but one of the men in confinement, and permission was given to us to move unrestricted within certain specified limits. The Japanese made it abundantly clear that they intended to take over our property. Planes dropped leaflets urging foreigners to “evacuate as soon as possible to avoid possible danger”; the Japanese every few weeks required a new set of statistics concerning our personnel; they laboriously measured our houses and land; they insisted on our surrendering Church property, they began baseball matches while we were playing cricket; they labelled all the furniture. One day four of us were ordered to meet the garrison commander, who ordered the evacuation of certain buildings to begin on August 12. By November 5, 1942, the compound was entirely denuded of members of the China Inland Mission.

Camp I

The Japanese housed 167 boys and girls and 74 adults belonging to the C.I.M. in four houses built for four families of Americans at the West of Chefoo. The sun was shining, I well remember, as we passed down the drive of our compound for the last time, I was with almost the last party of boys. We were a motley crowd well-loaded with an amusing assortment of personal goods packed in knapsacks, strapped to bicycles or suspended from belts, shoulders or arms. Undefeated, we determined to leave in triumph. We amazed the sentries and some Chinese passers-by by singing as we left.

“God is still on the throne

And he will remember his own … “

During the next ten months my family and I lived with forty-two others in a house previously occupied by four. For six months my wife, two daughters and myself shared a room with another family. Our mattresses – we had no bedsteads – covered most of the floor space. Twelve boys slept in the attic; three ladies slept in a garage. With no servants and entirely inadequate sanitation we were kept very busy coping with the exigencies of life; sawing and chopping wood, making seats doing repairs, stoking stoves, cooking in most confined quarters and waging the daily struggle to secure enough to eat. Washing accommodation was a perpetual problem, as was the provision of hot water in the cold months. By careful organization we were eventually able to arrange a modified scheme of education and to relieve the monotony for the boys and girls by various games and entertainments.

Being in control of houses, at some distance from each other, the Japanese guards left us alone except for the two daily roll-calls; they stationed Chinese police at our gates who deserted us at night, when prowling thieves often attempted to rob us. When a theft of bicycles occurred one night, the Japanese told us they would take away the rest of the bicycles in our possession to look after them for us. Needless to say, we never saw them again. Their “taking” ways provided us with amusement.

Again and again we recorded instances of answered prayers when supplies of coal or flour had run out. The Chief of Police was always courteous in our first camp and there was no maltreatment. Religious liberty was granted, the only restriction being that addresses must be censored by the authorities before they could be delivered.

Restrictions, monotonous drudgery, pressure of work, lack of privacy, and scant news of relatives, began to tell on the spiritual stamina of some. A long period of “drought” came to a gradual end when one after another had a new experience of the power of Christ, mainly through the testimony of a senior boy and the prayers and personal contacts which followed. A wonderful sense of unity prevailed.

The friendship of an “enemy alien” was a great solace. He brought us news, made purchases for us and was a channel for obtaining funds, and he did it at considerable risk. Why? Because his love for his brothers and sisters in Christ transcended his love for his own reputation as a German. It was a beautiful reminder to us of the unity of all believers in Christ.

Camp II

Scenes of almost indescribable confusion, luggage of every description piled dangerously high, the whack of a stick on my back from a Japanese guard, a last minute recovery of a stolen trunk, a lengthy procession to a jetty; these are some of my recollections of the days before we set sail in a dangerously overloaded steamer for Tsingtao. At the station we were confidently told we should be repatriated in three months. With light hearts, we faced a new camp a hundred odd miles east of Tsingtao, near Weihsien. It was September 9, 1943, when we arrived to meet entirely new conditions.

We found ourselves in a huge American campus built for a thousand Chinese students. School and lecture rooms had been converted into dormitories for single men and women, and row after row of one-roomed houses accommodated the married folk with their families. My family lived with the school in high ceilinged-rooms, bare of every convenience or piece of furniture till our trunks arrived after much delay. Dirt and lack of floor space were perpetual problems. Warm weather provided the necessary incentive to thousands of creatures which thrive on human flesh to leave their winter hiding places. Daily warfare thinned their ranks, but their counter-attacks never ceased.

We mealed in huge kitchens, seated at bare boards. The staple diet was stew. The Japanese professed to provide sufficient meat, flour, peanut oil, grain and vegetables for two meals a day for the 1,500-odd people in camp. As the days wore on, food conditions grew worse. When our cooks were at their wits’ end in January 1945, an American Red Cross parcel arrived for each individual in camp – just in time. Fuel by that time was coal-dust which we made into coal-balls by baking in the sun a mixture of clay, water and coal-dust. This burned slowly in the stoves and generated a good heat in a small room.

After two men had escaped from the camp, roll-calls were doubled and electrified wire was placed on the outer wall of the camp. As a school, we were moved to the upper rooms of the hospital, whence we had extensive views of the lovely surrounding country with its meandering stream. Each was allotted his work. The handy man was at a premium, for every type of job, unskilled and skilled was needed, from a doctor or educationist to a stoker or cobbler. Nothing was wasted. Exhibits in camp of home-made gadgets revealed remarkable inventiveness and skill. Everyone washed his own clothes. Queues abounded for hot and cols water, for the canteen, for meals, for coal-dust, for milk, for children under eight and old people. Clothing was well patched or made from such material as towelling and curtains. The camp was well administered by a committee of Nine elected men. Every grade of society was represented. Public opinion and the healthy influence of a number of missionaries preserved the camp from demoralization. But standards were low in some quarters and many temptations abounded, especially for the young.

From the first the united Christian witness of the Christian Fellowship had a salutary effect on the Camp. The Sunday evening evangelistic song service was highly appreciated by many non-churchgoers. Many contacts were made through those services, but few were “saved.” Many considered the claims of Christ as never before and business men acknowledged to me that they could sense “power” in the lives of Christians. Barriers between business folk and missionaries were swept away; Christians while agreeing to differ on the interpretation of truth, found prayer with men of different schools of thought a most uniting force.

I would not have missed this experience for anything. I learned to understand the temptations of the poor to covet, to steal and to lose moral sense; I learned to appreciate the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ in the lives of believers with whom I should normally not have associated; I learned to be completely satisfied with Christ when earthly treasures failed; I know in a deeper way than I could have proved before, that the invisible is real; I proved that a faith based on the Living though Crucified Saviour and on His inerrant Word stood the test of three years’ internment.

***

by Stanley Houghton

April 25, 1946.

April 25, 1946.

... the same map as seen on Google Earth. Hover on the pictures to zoom.

This leaflet was dropped over Chefoo in February 1938, when the Japanese took occupation of the port. British and American residents were regarded as neutrals until the Pearl Harbor raid on 8 December 1941. The Chefoo community were interned at Temple Hill in November 1942, and were transferred to Weihsien Camp in September 1943.

Translation:

The Japanese Army is coming soon to protect Japanese civilians living in China. The Japanese Army is an army of strict discipline, protecting good citizens. Civil servants must seek to maintain peace and order. Members of the community must live together peacefully and happily. With the return of Japanese businessmen to China, the businesses will prosper once more. Every house must fly a Japanese flag to welcome the Japanese.

JAPANESE ARMY HEADQUARTERS

House arrest et Temple Hill -- Chefoo.

Weihsien:

Entrance of the camp, taken from the inside. To the right was the Italian sector.

It was Mrs. Eileen Bazire who sketched this picture. It is at the front of a little book In Whose Hands? A story of Internment in China by George A. Scott.

© Peter Bazire,

MAP OF WEIHSIEN - 1943

![1924 map of Chefoo [click here] 1924 map of Chefoo](image/image.jpg)

![© Google Earth [click here] © Google Earth](image/Chefoo.jpg)

![House arrest et Temple Hill [click here] House arrest et Temple Hill](image/TempleHillMap.jpg)

![House arrest et Temple Hill [click here] House arrest et Temple Hill](image/TempleHill.jpg)

![House arrest et Temple Hill [click here] House arrest et Temple Hill](image/TempleHill2.jpg)

![Entrance of camp, taken from the inside. [click here] Entrance of camp, taken from the inside.](image/TheGate.jpg)

![MAP OF WEIHSIEN - 1943 [click here] MAP OF WEIHSIEN - 1943](image/map500pix.jpg)