FORTY YEARS AGO IN A JAPANESE CAMP...

On a blistering hot day in August, 1945, away in the countryside of the northerly Chinese province of Shantung, 1500 civilian prisoners of the Japanese were doing their normal manual tasks in a former mission compound 200 yards long by 150 yards wide, and surrounded by two ranges of electrified wires.

Their community work included pumping water by rota, stirring thin soup or bread porridge in large Chinese caldrons, baking bread in massive camp-made ovens. They were a motley crowd of people ― from very young to very old, they were barefooted, in tattered clothes and with sunburnt complexions; their features were Anglo-Saxon, white Russian, Eurasian and Continental.

What they knew about events in the outside world and of the war theatre in particular was meagre indeed. One night fourteen months previously, when the Japanese soldiers were changing guard and therefore momentarily disorganised, and when the full moon shining on the sentry's tower cast its long shadow over a large area of the outside wall, two men with the help of fellow prisoners had made a well planned escape through the wires and joined a guerrilla band 100 miles from the camp. Later an American plane parachuted a radio to them.

Hummel and Tipton conveyed the barest news of the war to Weihsien camp in a most ingenious way. Chinese coollies entered the camp daily to clear the cess pools. At the gates they were carefully searched by guards and often hit with the butts of their rifles. One of their number, carrying empty buckets on his shoulders, would have information wrapped in a pellet stuffed up his nose, and on passing a particular rubbish dump cleared his sinuses and discharged his message.

From these terse newsflashes it was clear that Japan was losing the war in the Far East and was on the point of surrender. This was good news indeed, but it held with it fear and uncertainty. As I dumped some crates of ash outside the camp gate about this time, and stretched my limbs whilst the dust settled, a Japanese guard told me in a mix of Chinese, Japanese and sign language that should they lose the war they would shoot us and then fall on their swords.[click here]

Rescue from the skies...

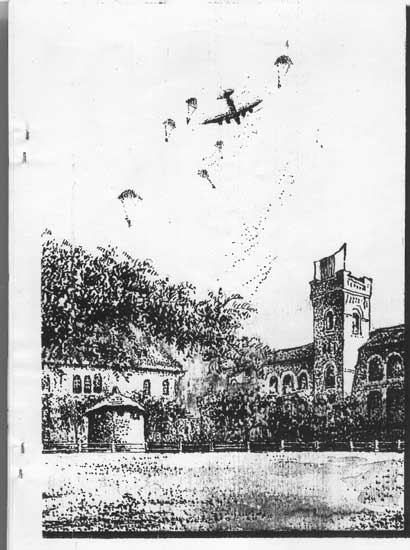

Thus it was that on Friday, 17th August, the prisoners in Weihsien Camp heard the distant drone of a plane. The sound grew louder ― it sounded somehow more musical than the Japanese planes they had often heard when China was being occupied seven years before. Something instinctive stirred in each prisoner's heart ― "This is it ― the end is here." Dropping their work they rushed outside and looked skywards.

The American B24 was trying to identify the Camp from the Chinese villages in the countryside. Soiled British and .American flags, which had been concealed in the bottoms of trunks "for the duration", were hastily unpacked and waved horizontally. The plane circled closer and closer, and then, believe it or not, beyond the treetops in front of the main gate it disgorged a parachute, which we could see fluttering gently down. Six others followed in quick succession...

They found the Japanese soldiers standing at attention in the guard room just inside the main gate with their rifles stacked in one corner, overcome by the speed of events that hot August morning. To their surprise Major Staiger commanding the rescue team and communicating to them through Sergeant Nagaki, a Japanese American, instructed them to re-arm themselves and assist their new American leader. In the countryside surrounding the Camp rival Kuo Min Tang and Communist soldiers with their common enemy vanquished were already in battle with one another. It was important that the 1500 internees, who had survived the hazards of the protracted war with Japan, should not now be endangered by the fast spreading civil war. The instructions to resume duties under the conquering Americans added a further twist to the morning's programme of drama.

In touch with Civilisation.

From then on whenever the opportunity permitted we surrounded these deities from the sky, and plied them with questions about the outside world and the political events of the past years.

I was a cook on a labour gang in Kitchen I which catered for 600 people ― our basic commodity bags and bags of flour. From this we had made faith as much variation as circumstances permitted bread porridge, bread pudding and bread-based concoctions.

And so when on that first Friday evening two members of the relief team honoured Kitchen I with their presence we planned a special menu. Out of the small store room came some of the rarities we saved for Christmas and such occasions, and with our usual ingenuity we got to work. While the crowds queued up for a ladle of black tea served from a communal bucket and then for a dollop of that evening's variation of bread pudding, we served our two VIP guests a special meal from our hoarded resources. (Quietly and politely the food was left uneaten; our special menu was quite unpalatable.

But better meals were soon coming.

Manna from heaven.

The weeks following brought many changes to our mode of living. The sudden cessation of fighting in the Pacific had meant that boxes of food, medicines and clothes were no longer needed in the war theatre, and so these were re-directed to civilian camps in Weihsien and Shanghai.

Planes arrived daily dropping supplies of powdered milk, butter, spam, chocolate, sugar, as well as khaki uniform, underwear and medical drugs.

I stood one day in front of the Japanese guard room looking up into the sky. Blue, green and red parachutes were floating down from the silver bellies of American military planes on to the cornfields half a mile in front of me. All the things we had so desperately needed during those two years of imprisonment were falling from the skies in abundance. Manna was coming down from heaven. I recalled the words of the Psalmist:

"Thou spreadest a table before me in the presence of mine enemies. My cup runneth over. Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me all the days of my life; and I will dwell in the house of the Lord for ever." (Psalm 23.)

Unforeseen Hazards

But not all those welcome parcels fluttered down gently. Packed hurriedly at distant bases many crates hurtled down, ripping the parachutes, crashing to the earth and bouncing ten feet high, breaking into many pieces. At first we were caught unprepared and had some narrow shaves, as these large boxes rained down all around us, sometimes within a few feet.

An American officer, standing beside me after one of these downpours of parcels, shaken and out of breath, swore he had faced more hazards that day on the Weihsien fields than in other theatres of war in South East Asia. We soon learned to keep on the safe side of tall trees until the planes had gone.

Chinese peasants came out of their villages to witness the unforgettable scene of pools of soup, dented tins and scattered vitamin pills, their eyes boggling at the quantity and variety of the supplies, which had burst out of the broken boxes which had poured from the skies. Rumour had it that one farmer had eagerly devoured the equivalent of a bottle of vitamin pills, and with newly endowed energy was last seen still running somewhere north of Peking.

After the day's work of bringing the boxes from the fields into the "Courtyard of the Happy Way" (from the time when this compound was an American Presbyterian institution there were still three Chinese characters with this meaning on the front gate of Weihsien Camp) and doing our normal communal work we attended in the evening "Reorientation Classes" given by the American officers on recent world events. Our vocabulary was enlarged to embrace such new words as G.I., D Day, Jeeps, B24, Mulberry Harbour and Kamikaze.

Impatient to depart

Soon even the novelty of square meals, wearing shoes on one's feet and walking freely out of the Camp gates began to wear thin, and repatriation and reunion with our families became one's burning passion and obsession.

Although peace had come to the world it had not come to our locality. At night time we could see and hear gunfire in the distance as rival Communist and bandit groups bitterly fought each other. Thus to get 1500 prisoners to Tsingtao at the coast, a distance of 125 miles, meant a train journey through these danger zones. The Americans offered a large sum of money to these groups if they would desist from fighting for an agreed upon period, during which time they would arrange our evacuation.

On 25th September, 1945, five weeks after our dramatic rescue from the skies, I clambered on a lorry near the Moongate where the Camp administration was based. In one suitcase were all my belongings ― clothes recently dropped by parachute, school and family photographs and a strange assortment of souvenirs of my recent chapter ― some green silk ripped from an American parachute, some leaflets which had been dropped by the planes and a Japanese guard's helmet.

It was exciting indeed to be travelling out through the gate of "The Courtyard of the Happy Way"' to the great wide open world outside, but I was experiencing something else which I had not anticipated ― a sense of being wrenched from the midst of a vast cosmopolitan community of men and women of diverse cultures and backgrounds ― academics, business executives, prostitutes, nightclub bandsmen, priests and missionaries. A large closely knit family which for three years had laughed and cried and laboured together was being torn apart.

Weihsien revisited

Small wonder that a place with such conflicting memories drew my sister and me back last year while we were on an organised tour of China's cities, after an absence of 39 years. Weifang, as the town is now called, is today a thriving industrial area. One half of the former Camp is now a large educational complex and the other half is the Weifang People's Hospital. Of course the electric wires and high walls have gone, and in 39 years much has changed.

We walked the roads and alleys of former days, and saw the long rows of tiny rooms nine foot by twelve foot in which the families had stayed, the large bachelor dormitories, the sports field where Eric Liddell of "Chariots of Fire" fame had with limited resources organised games for the young. We found the spot though overgrown with bushes where in June 1945 we lovingly laid the earthly remains of this former Olympic hero to rest. We saw the spaces where in the extremes of heat and cold we had lined up twice daily for Rollcall.

Walking to what was once the front of the Camp, and is now the back of the college grounds we found that the imposing gate with its three Chinese characters had gone, but we noticed that the local Chinese still refer to the locality as "Lo Tao Yuan" ― "Courtyard of the Happy Way". Names die hard.

For the 1500 prisoners who were held there by the Emperor of Japan it was not a "happy way". It was more accurately the "Courtyard of Invaluable Lessons". As Hugh Hubbard, American missionary and camp leader wrote in a friend's autograph album during those darker days:

Weihsien is the Test ― whether a man's happiness depends on what he has, or what he is; on outer circumstance or inner heart; on life's experiences, good and bad ― or on what he makes out of the materials those experiences provide...

Or as Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote after he left his Soviet cell,

"Bless you prison, bless you for having been in my life."'

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

A fuller account is given in the author's book "Courtyard of the Happy Way", published by Arthur James Ltd., The Drift, Evesham, Worcs.

Please write to: DR. NORMAN H. CLIFF, 4 HALL TERRACE, HAROLD WOOD, ESSEX RM3 OXR. U.K.

The Children of Weihsien

... just click on the cover of the book and scroll to page -210.

A Google-Map picture and a superposition of the Weihsien Camp Map: you will be able to visualize the whole surface allocated to ± 1500 men, women and children by out Japanese captors.

... and the various explanations from the children of Weihsien ...

THE ACTUAL ESCAPE ON

9 JUNE, 1944 and PREPARATIONS FOR THE END...

Tipton and Hummel slipped into the watchtower at the corner of the sports field, and through it, over the electrified wires with the help of fellow internees, while the Japanese sentry fresh on duty was doing his ten minute tour of inspection. A small group of Chinese were waiting for them, as arranged, at a cemetery two miles from the camp. Walking, travelling by wheelbarrow and bicycles, they reached the headquarters of General Wang Yumin and his guerrillas less than a hundred miles to the north east of Weihsien Camp.

Here they remained until the end of the war. They sent a lot of information about the camp to Chongqing, and obtained funds and medical supplies for the internees. They also kept in regular touch with the camp through a Chinese carpenter, who went in regularly as a labourer. The messages were written in fine silk, and folded into a small pellet, which the workman stuffed up his nose. This strategy defied the most exacting body searches. The messages were written in a special code in case they fell into the wrong hands. Sometimes they were spat out near a camp toilet where Fr. Raymond J. de Jaegher was already waiting.

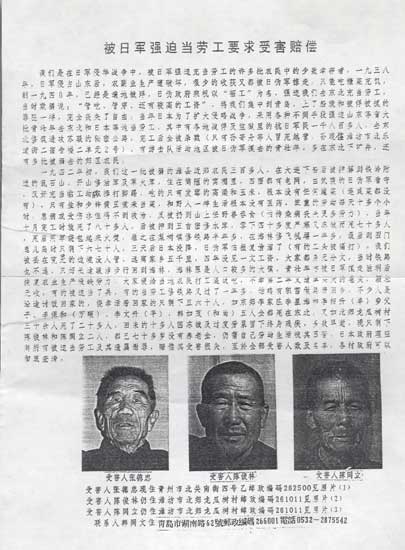

The basis of this feverish and clandestine correspondence was partly due to the increasing shortage of food and medicines, but even more importantly to the fear that when the war ended the Japanese might slaughter the camp inmates, or the internees might be caught in dangerous crossfire between competing bands of guerrillas.

Here is a selection of letters which were smuggled into camp with the purpose of making plans about the end of the war and ensuring that the internees were kept in safety.

In the following letter Wang Shao wen stated that his purpose was "to save you all out from Ledaoyuan [Courtyard of the Happy Way] and then send you back to your country". He asked for statistics of the numbers of men, women and children, and for a sketch map of the area around the camp.[click here]

[click on the picture] :

... a series of high definition photographs snaped by the crews of low flying B-29s in August 1945 whilst parachuting drums of food and clothing over - Weihsien Concentration Camp.

[click on the picture]

... various reproductions of documents (flyers) treasured by the de Saint Hubert family who were imprisonned in Weihsien too!

... [click on the picture]

and enjoy reading the few pages from Peter Bazire's dairy relating to our liberation and the days after as seen in the eyes of a young teenager ...

(Peter was 14, in 1945)

The Rev. Mr. And Mrs. Cliff, who for 20 years did missionary work in China, are shown welcoming their three children,, who have been prisoners of war for three and a half years. Captured while they were at school in China, the children were released by American troops. Two members of the same camp escaped and lived only 17 miles away from the Japanese. Return To Parents

Children Interned By Japanese

The happiest people in Durban yesterday were the Rev. and Mrs. H. S. Cliff, who up to Japan’s march into China had been missionaries there for 20 odd years.

Meeting the B.O.A.C. flying boat, they had come to welcome their three children, from whom they had been separated for four years. The Rev. Cliff in an interview with a “Natal Mercury” representative told how, when Pearl Harbour was bombed and war was declared; the children were at school at Chefoo, in North-Eastern China.

INTERNED

They were interned in their own compound at first, but later were transferred to Weihsien in Shantung Province. We managed to get mail to them by fooling the Japanese. We wrote all our letters in Chinese and posted them through the ordinary mail. They were all received. Later the Japanese found out and letters became very few and far between.

“Camp life was organized to such an extent that in the end my two daughters were able to take their matriculation there. We are waiting for the results now.

RUSHED GATES

They were released by American parachutists, who baled out after the aeroplanes had circled round the camp. Seeing the aircraft, the whole camp just rushed the gates and forced their way out. The parachute troops said later that this probably saved their lives, as the Japanese were so bewildered that hey offered no resistance.

“After three or four weeks they left for Tsingtao where they boarded a transport and sailed for Colombo, via Singapore. They then went on to the Middle East, and now at last we have them home”

***

![The Children of Weihsien - Book TWO - [click here] The children of Weihsien](../../../I_Remember/ALBUM/Book_2/TN_Cover.jpg)

![[click here] and read the confidential messages ... about the escape](../../../NormanCliff/paintings/exterior.gif)

![[click here] #](../../../DavidB/aerialPhotos/01-550pix_web.jpg)

![[click here] - various documents (flyers) from the deSaint Hubert family imprisonned in Weihsien. B-29 over Block-23](../../../Christian_deSaintHubert/photos/Block-23.jpg)

![[click here] #](../../../PeterBazire/diaryBook/083b.jpg)

![[click here] #](../../../NormanCliff/epilogue/BackHome2/ChildrenInterned.jpg)

![[click here] to read the book ... #](../../../NormanCliff/Books/Courtyard/Frontcover.jpg)