52 years later, ex-pow thanks her rescuers

Search for WWII vets a

"family affair"

By MELANIE BURNEY The

Associated Press 1998

BLACKWOOD - It took more than 50

years, but Mary Previte finally got a chance to say thank you to the World War

II rescuers who freed her from a Japanese prison camp.

She never forgot

the seven paratroopers who dropped from a low-flying B-29 bomber on a

sweltering summer morning in China shortly after the war ended.

But it was only

recently that she completed a cross-country search for them. She contacted four

by telephone, learned that two were dead and concluded it would be nearly

impossible to find the seventh.

|

| Associated Press photos

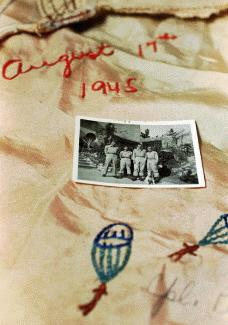

Mary Previte of Haddonfield received this yellowed parachute

from the widow of Peter Orlich, one of seven paratroopers who freed

her from a Japanese prison camp on Aug. 17, 1945. The parachute is embroidered

with each man's signature. |

"It was like

an unfinished business." says Previte, 65, of Haddonfield. "Never

in my wildest dreams did I think I would ever be able to find all of these

people."

After numerous

telephone calls, wrong numbers, unanswered letters and disappointments. she

finally got a chance to say thank you and reminisce with her rescuers.

"It's never too late to say thank you," Previte said in an interview last week. "It's been like goosebumps up and down my spine to be able to say thank you to these men after 52 years I told them I have so much to be thankful for."

The men, now all

in their 70s, some in failing health. appreciate her efforts, but say no thanks

were needed. They were proud to carry out what was known as the "DUCK

Mission."

"We did our

job. not knowing what would happen when we parachuted in," said Maj. Stanley Staiger, 79, of Reno. Nev..

the mission's commander. We had a few rough moments with the Japanese, but

everything worked itself out."

Previte was 12

years old when the paratroopers landed on Aug. 17. 1945, just outside the gates

of the Weihsien Civilian Assembly Center. The men were sent by the Office of

Strategic Services (OSS), the forerunner of the CIA, to liberate 1.400 captives

taken by the Japanese during the war.

At the time of

the Japanese invasion, Mary and her three siblings were studying at a hoarding

school for children of American and British missionaries called the Chefoo

School.

The Japanese

converted the strategically located school on the coast into a military base.

The children and teachers were taken to the prison camp just across the

Shandong peninsula. where they awaited the end of the war.

Previte's

parents, Methodist missionaries working in central China. were never taken

prisoner

The rescuers,

recalls Previte, were like "angels falling from the sky." The men,

unable to land at the camp because of Japanese guards, made a low drop into a

nearby cornfield.

"It worked

out beautifully," said James Moore, 78, of Dallas, one of the jumpers.

"It was an exciting time for me."

A Salvation Army

band began playing "The Star-Spangled Banner" and the freed prisoners

hoisted their rescuers onto their shoulders. At last, the war was over and

suddenly they were free.

"The camp

went berserk. We didn't know the war was over." recalled Previte.

"People were dancing, weeping, pounding the ground."

It would tae

weeks for Mary and her siblings, to be reunited with their parents after a 5

1/2-year separation.

|

This photograph taken in northeast China in 1945 depicts `DUCK Mission' rescue team members, from left, James Moore, Tad Nagaki, Stanley Staiger and Raymond Hanchulak. The men, now all in their 70s, appreciate Previte's efforts, but say no thanks were needed. |

Forty years later,

in 1985. Previte found the names of the seven rescuers when she obtained a

copy of the declassified military mission report from a fellow camp survivor.

She tucked it away, thinking it would be impossible to find them.

Previte began her

search on a whim while speaking last May in Mount Laurel to a reunion of

veterans in the China-Burma-India theater. She read off the seven names, but no

one knew them. One man took her phone number, offering to help with the search.

The first lead

came in October: the widow of Raymond

Hanchulak was living in central Pennsylvania in Bear

Creek Village. Her husband, a medic on the mission, died the previous year.

Meanwhile,

Previte received pages and pages of names gleaned from the Internet to check

out. The search seemed daunting: there were more than 150 names - just for

James Moore.

Then she found Peter Orlich's widow. Carol, in

Queens, N.Y. Her husband, a radio operator and the youngest of the group, died

in 1993 at the age of 70. He. too, had tried to locate the others, but never

did, she said.

"If he were

only alive - what this would have meant to him. It's just hard for me to

imagine," Mrs. Orlich said.

S e sent Previte

a piece of yellowed silk parachute embroidered with the men's signatures that

her husband had kept in his dresser drawer.

"Now I was

really heartsick because my first two connections were with two widows,"

Previte said. "I thought, 'I could not wait one more minute to start

calling every name on this list.'"

She found Tad

Nagaki, a Japanese American interpreter on the mission. Now 77, he is a

recently widowed beet farmer in Alliance. Neb. Nagaki sent Previte photographs

his wife kept in a wartime scrapbook.

Nagaki told Previte

how to find Moore, who attended the same Chefoo missionary school before joining

the FBI and then the OSS. He later joined the CIA and retired in 1978.

|

| 'It's never too late to say thank you.

We were bonded by a war that wrapped us together for so many different

reasons. We've become family now.' - Mary Previte |

Moore, with help

from a neighbor with a national computer database, joined Previte's search for

the remaining men. He found Staiger, 79, recovering from a broken hip at his

Nevada home. The last, James Hannon, was located by Moore in Yucca Valley,

Calif.

Previte ended her

search without locating the seventh man, Eddie Wang, the Chinese interpreter.

The others said he was a Chinese nationalist and they had no idea how to find

him.

With her search

over, Previte has been getting to know her rescuers and what happened to them

after the war. They were surprised by her interest in their lives.

"I don't

think we made that much of a difference. It could have been anybody,"

Moore said modestly. "It's nice of her to remember us."

Staiger became a

stock broker and a hotel owner before retiring in Reno. Hannon is a writer,

drafting plot summaries about the war.

Previte, who was

elected earlier this month to the state Assembly. told the men about her life

as the administrator of the Camden County Youth Center in Blackwood and mother

of an adult daughter.

She would like to

organize a reunion for the group, but the men's failing health may prevent that.

Either way, Previte plans to keep in touch.

"We were

bonded by a war that wrapped us together for so many different reasons,"

Previte said. We've become family now"